Meeting the potential of immunotherapy: new targets provide rational combinations

Citation JCSO 2017;15(2):116-121

©2017 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0336

Submit a paper here

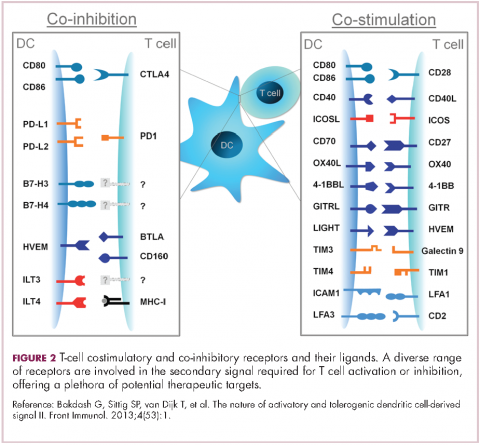

To become fully activated, T cells require a primary signal generated by an interaction between the TCR and the antigen-MHC complex on the surface of an APC, followed by secondary costimulatory signals generated by a range of different receptors present on the T-cell surface binding to their ligands on the APC.

If the second signal is inhibitory rather than stimulatory, then the T cell is deactivated instead of becoming activated. Two key coinhibitory receptors are programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and tumor cells are able to overcome the anti-tumor immune response in part by expressing the ligands that bind these receptors to dampen the activity of tumor-infiltrating T cells and induce tolerance.13

The development of inhibitors of CTLA-4 and PD-1 and their respective ligands has driven some of the most dramatic successes with cancer immunotherapy, particularly with PD-1-targeting drugs which have fewer side effects. Targeting of this pathway has resulted in durable responses, revolutionizing the treatment of metastatic melanoma, with recently published long-term survival data for pembrolizumab showing that 40% of patients were alive 3 years after initiating treatment and, in a separate study, 34% of nivolumab-treated patients were still alive after 5 years.14,15 More recently, PD-1 inhibitors have been slowly expanding into a range of other cancer types and 4 immune checkpoint inhibitors are now approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA): ipilimumab (Yervoy), nivolumab (Opdivo), pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and atezolizumab (Tecentriq).

,Six years on from the first approval in this drug class and an extensive network of coinhibitory receptors has been uncovered – so-called immune checkpoints – many of which are now also serving as therapeutic targets (Table, Figure 2).16 Lymphocyte activation gene 3 (LAG-3) is a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily of receptors that is expressed on a number of different types of immune cell. In addition to negatively regulating cytotoxic T-cell activation like PD-1 and CTLA-4, it is also thought to regulate the immunosuppressive functions of regulatory T cells and the maturation and activation of dendritic cells. T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing 3 (TIM-3) is found on the surface of helper and cytotoxic T cells and regulates T-cell inhibition as well as macrophage activation. Inhibitors of both proteins have been developed that are being evaluated in phase 1 or 2 clinical trials in a variety of tumor types.17

Indeed, although T cells have commanded the most attention, there is growing appreciation of the potential for targeting other types of immune cell that play a role in the anti-tumor immune response or in fostering an immunosuppressive microenvironment. NK cells have been a particular focus, since they represent the body’s first line of immune defense and they appear to have analogous inhibitory and activating receptors expressed on their surface that regulate their cytotoxic activity.

The best-defined NK cell receptors are the killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs) that bind to the MHC class I proteins found on the surface of all cells that distinguish them as ‘self’ or ‘non-self’. KIRs can be either activating or inhibitory, depending upon their structure and the ligands to which they bind.19 To date, 2 antibodies targeting inhibitory KIRs have been developed. Though there has been some disappointment with these drugs, most recently a phase 2 trial of lirilumab in elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia, which missed its primary endpoint, they continue to be evaluated in clinical trials.20

The inhibitory immune checkpoint field has also expanded to include molecules that regulate T-cell activity in other ways. Most prominently, this includes enzymes like indoleamine-2,3 dioxygenase (IDO), which is involved in the metabolism of the essential amino acid tryptophan. IDO-induced depletion of tryptophan and generation of tryptophan metabolites is toxic to cytotoxic T cells, and IDO is also thought to directly activate regulatory T cells, thus the net effect of IDO is immunosuppression. Two IDO inhibitors are currently being developed.21