A True Community: The Vet-to-Vet Program for Chronic Pain

Background: The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has evolved its approach to chronic pain management, emphasizing the social context of pain and self-management strategies.

Observations: This article describes the implementation of Vet-to-Vet, an interpersonal group that personifies this shift in VHA strategy by combining mutual help, mindfulness, and storytelling in weekly virtual meetings led by veterans experiencing chronic pain. An evaluation of the Rocky Mountain Regional Veterans Affairs Medical Center Vet-to-Vet group indicated high engagement, with many participants attending for ≥ 6 months. Qualitative findings highlight the program’s positive impact, particularly in fostering connections among veterans, facilitating mutual support, and empowering participants to better manage pain and become stronger advocates for their care. Participants reported improvements in accessing help, positive health outcomes, and addressing the psychological aspects of pain.

Conclusions: Vet-to-Vet shows promise as an approach to chronic pain care that aligns with VHA whole health strategies. An ongoing evaluation will explore program effectiveness as it expands to additional sites, with the goal of embedding peer support and mutual help across various contexts.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has continued to advance its understanding and treatment of chronic pain. The VHA National Pain Management Strategy emphasizes the significance of the social context of pain while underscoring the importance of self-management.1 This established strategy ensures that all veterans have access to the appropriate pain care in the proper setting.2 VHA has instituted a stepped care model of pain management, delineating the domains of primary care, secondary consultative services, and tertiary care.3 This directive emphasized a biopsychosocial approach to pain management to prioritize the relationship between biological, psychological, and social factors that influence how veterans experience pain and should commensurately influence how it is managed.

The VHA Office of Patient-Centered Care and Cultural Transformation implemented the Whole Health System of Care as part of the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, which included a VHA directive to expand pain management.4,5 Reorientation within this system shifts from defining veterans as passive care recipients to viewing them as active partners in their own care and health. This partnership places additional emphasis on peer-led explorations of mission, aspiration, and purpose.6

Peer-led groups, also known as mutual aid, mutual support, and mutual help groups, have historically been successful for patients undergoing treatment for substance use disorders (eg, Alcoholics Anonymous).7 Mutual help groups have 3 defining characteristics. First, they are run by participants, not professionals, though the latter may have been integral in the founding of the groups. Second, participants share a similar problem (eg, disease state, experience, disposition). Finally, there is a reciprocal exchange of information and psychological support among participants.8,9 Mutual help groups that address chronic pain are rare but becoming more common.10-12 Emerging evidence suggests a positive relationship between peer support and improved well-being, self-efficacy, pain management, and pain self-management skills (eg, activity pacing).13-15

Storytelling as a tool for healing has a long history in indigenous and Western medical traditions.16-19 This includes the treatment of chronic disease, including pain.20,21 The use of storytelling in health care overlaps with the role it plays within many mutual help groups focused on chronic disease treatment.22 Storytelling allows an individual to share their experience with a disease, and take a more active role in their health, and facilitate stronger bonds with others.22 In effect, storytelling is not only important to group cohesion—it also plays a role in an individual’s healing.

Vet-to-Vet

The VHA Office of Rural Health funds Vet-to-Vet, a peer-to-peer program to address limited access to care for rural veterans with chronic pain. Similar to the VHA National Pain Management Strategy, Vet-to-Vet is grounded in the significance of the social context of pain and underscores the importance of self-management.1 The program combines pain care, mutual help, and storytelling to support veterans living with chronic pain. While the primary focus of Vet-to-Vet is rural veterans, the program serves any veteran experiencing chronic pain who is isolated from services, including home-bound urban veterans.

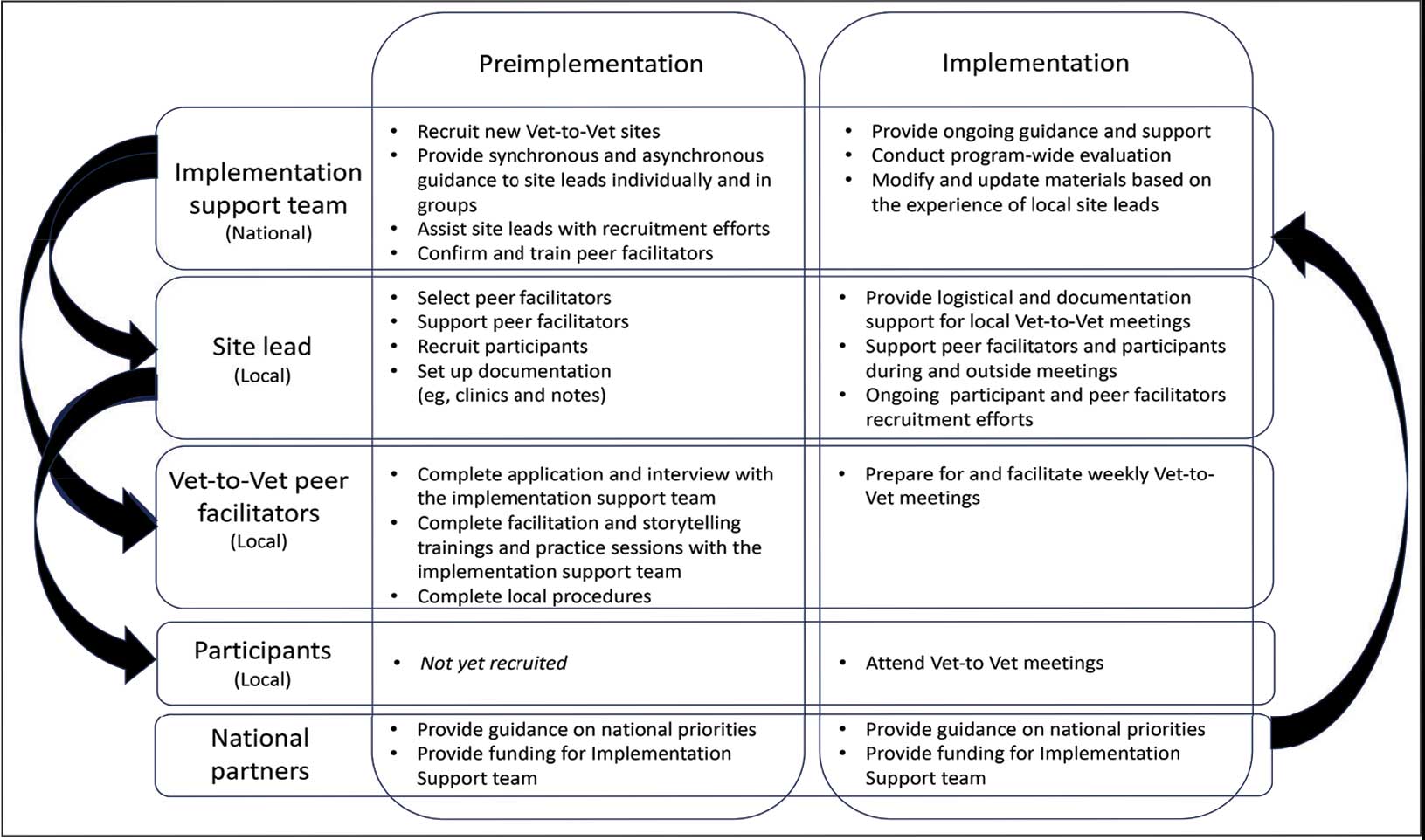

Following mutual help principles, Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators lead weekly online drop-in meetings. Meetings follow the general structure of reiterating group ground rules and sharing an individual pain story, followed by open discussions centered on well-being, chronic pain management, or any topic the group wishes to discuss. Meetings typically end with a mindfulness exercise. The organizational structure that supports Vet-to-Vet includes the implementation support team, site leads, Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators, and national partners (Figure 1).

Implementation Support Team

The implementation support team consists of a principal investigator, coinvestigator, program manager, and program support specialist. The team provides facilitator training, monthly community practice sessions for Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators and site leads, and weekly office hours for site leads. The implementation support team also recruits new Vet-to-Vet sites; potential new locations ideally have an existing whole health program, leadership support, committed site and cosite leads, and ≥ 3 peer facilitator volunteers.

Site Leads

Most site and cosite leads are based in whole health or pain management teams and are whole health coaches or peer support specialists. The site lead is responsible for standing up the program and documenting encounters, recruiting and supporting peer facilitators and participants, and overseeing the meeting. During meetings, site leads generally leave their cameras off and only speak when called into the group; the peer facilitators lead the meetings. The implementation support team recommends that site leads dedicate ≥ 4 hours per week to Vet-to-Vet; 2 hours for weekly group meetings and 2 hours for documentation (ie, entering notes into the participants’ electronic health records) and supporting peer facilitators and participants. Cosite lead responsibilities vary by location, with some sites having 2 leads that equally share duties and others having a primary lead and a colead available if the site lead is unable to attend a meeting.

Vet-to-Vet Peer Facilitators

Peer facilitators are the core of the program. They lead meetings from start to finish. Like participants, they also experience chronic pain and are volunteers. The implementation support team encourages sites to establish volunteer peer facilitators, rather than assigning peer support specialists to facilitate meetings. Veterans are eager to connect and give back to their communities, and the Vet-to-Vet peer facilitator role is an opportunity for those unable to work to connect with peers and add meaning to their lives. Even if a VHA employee is a veteran who has chronic pain, they are not eligible to serve as this could create a service provider/service recipient dynamic that is not in the spirit of mutual help.

Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators attend a virtual 3-day training held by the implementation support team prior to starting. These training sessions are available on a quarterly basis and facilitated by the Vet-to-Vet program manager and 2 current peer facilitators. Training content includes established whole health facilitator training materials and program-specific storytelling training materials. Once trained, peer facilitators attend storytelling practice sessions and collaborate with their site leads during weekly meetings.

Participants

Vet-to-Vet participants find the program through direct outreach from site leads, word of mouth, and referrals. The only criteria to join are that the individual is a veteran who experiences chronic pain and is enrolled in the VHA (site leads can assist with enrollment if needed). Participants are not required to have a diagnosis or engage in any other health care. There is no commitment and no end date. Some participants only come once; others have attended for > 3 years. This approach is intended to embrace the idea that the need for support ebbs and flows.

National Partners

The VHA Office of Rural Health provides technical support. The Center for Development and Civic Engagement onboards peer facilitators as VHA volunteers. The Office of Patient-Centered Care and Cultural Transformation provides national guidance and site-level collaboration. The VHA Pain Management, Opioid Safety, and Prescription Drug Monitoring Program supports site recruitment. In addition to the VHA partners, 4 veteran evaluation consultants who have experience with chronic pain but do not participate in Vet-to-Vet meetings provide advice on evaluation activities, such as question development and communication strategies.

Evaluation

This evaluation shares preliminary results from a pilot evaluation of the Rocky Mountain Regional VA Medical Center (RMRVAMC) Vet-to-Vet group. It is intended for program improvement, was deemed nonresearch by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board, and was structured using the RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance) framework.23 This evaluation focused on capturing measures related to reach and effectiveness, while a forthcoming evaluation includes elements of adoption, implementation, and maintenance.

In 2022, 16 Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators and participants completed surveys and interviews to share their experience. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded in ATLAS.ti. A priori codes were based on interview guide questions and emergent descriptive codes were used to identify specific topics which were categorized into RE-AIM domains, barriers, facilitators, what participants learned, how participants applied what they learned to their lives, and participant reported outcomes. This article contains high-level findings from the evaluation; more detailed results will be included in the ongoing evaluation.

Results

The RMRVAMC Vet-to-Vet group has met weekly since April 2022. Four Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators and 12 individuals participated in the pilot Vet-to-Vet group and evaluation. The mean age was 62 years, most were men, and half were married. Most participants lived in rural areas with a mean distance of 125 miles to the nearest VAMC. Many experienced multiple kinds of pain, with a mean 4.5 on a 10-point scale (bothered “a lot”). All participants reported that they experienced pain daily.

Participation in Vet-to-Vet meetings was high; 3 of 4 peer facilitators and 7 of 12 participants completed the first 6 months of the program. In interviews, participants described the positive impact of the program. They emphasized the importance of connecting with other veterans and helping one another, with one noting that opportunities to connect with other veterans “just drops off a lot” (peer facilitator 3) after leaving active duty.

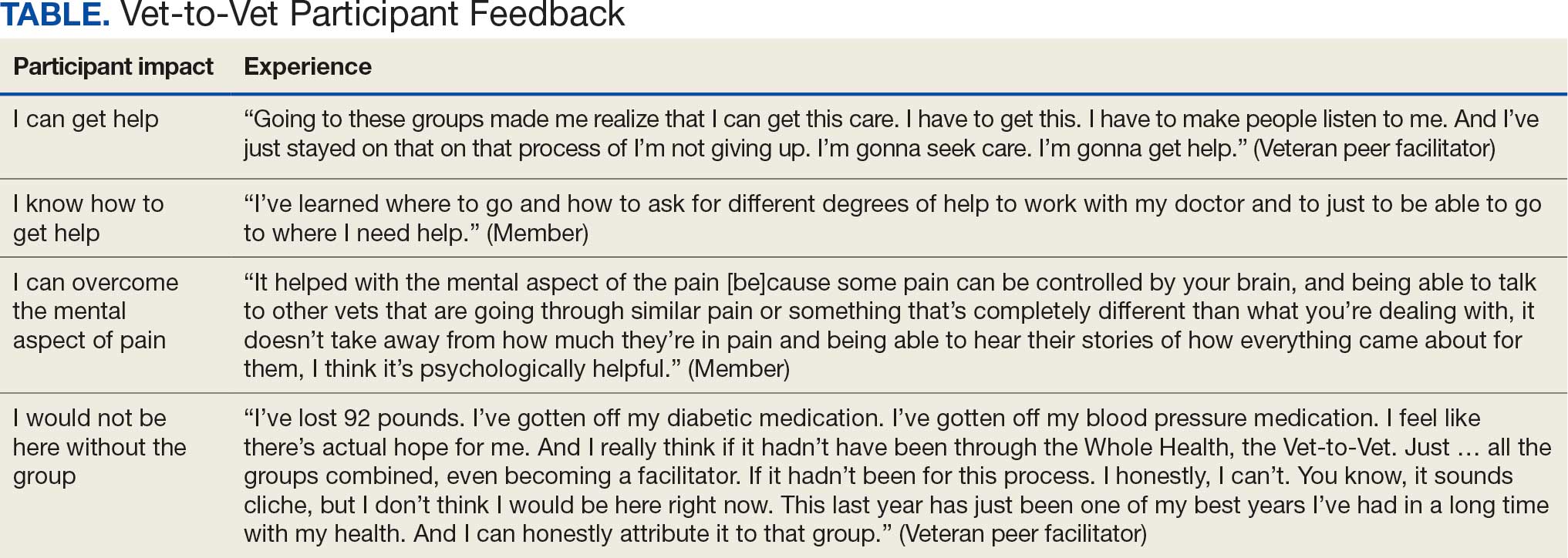

Some participants and Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators outlined the content of the sessions (eg, learning about how pain impacts the body and one’s family relationships) and shared the skills they learned (eg, goal setting, self-advocacy) (Table). Most spoke about learning from one another and the power of sharing stories with one peer facilitator sharing how they felt that witnessing another participant’s story “really shifted how I was thinking about things and how I perceived people” (peer facilitator 1).

Participants reported several ways the program impacted their lives, such as learning that they could get help, how to get help, and how to overcome the mental aspects of chronic pain. One veteran shared profound health impacts and attributed the Vet-to-Vet program to having one of the best years of their life. Even those who did not attend many meetings spoke of it positively and stated that it should continue so others could try (Table).

From January 2022 to September 2025, > 80 veterans attended ≥ 1 meeting at RMRVAMC; 29 attended ≥ 1 meeting in the last quarter. There were > 1400 Vet-to-Vet encounters at RMRVAMC, with a mean (SD) of 14.2 (19.2) and a median of 4.5 encounters per participant. Half of the veterans attend ≥ 5 meetings, and one-third attended ≥ 10 meetings.

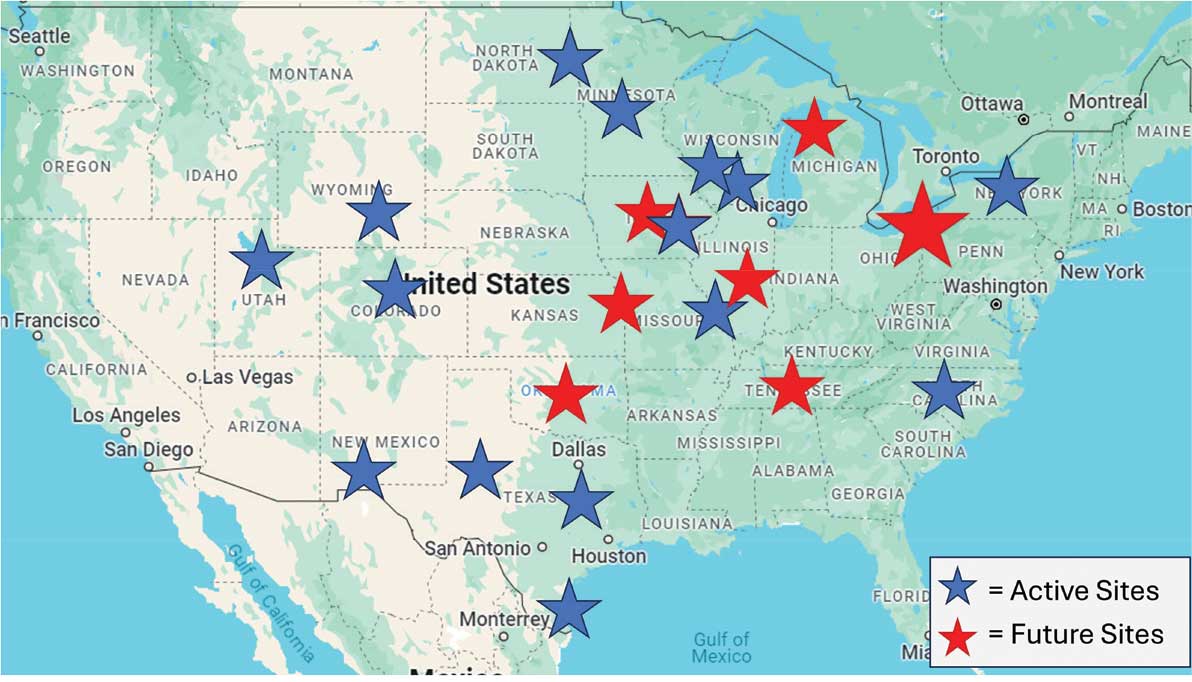

Since June 2023, 15 additional VHA facilities launched Vet-to-Vet programs. As of October 2025, > 350 veterans have participated in ≥ 1 Vet-to-Vet meeting, totaling > 4500 Vet-to-Vet encounters since the program’s inception (Figure 2).

Challenges

The RMRVAMC site and cosite leads are part of the national implementation team and dedicate substantial time to developing the program: 40 and 10 hours per week, respectively. Site leads at new locations do not receive funding for Vet-to-Vet activities and are recommended to dedicate only 4 hours per week to the program. Formally embedding Vet-to-Vet into the site leads’ roles is critical for sustainment.

The Vet-to-Vet model has changed. The initial Vet-to-Vet cohort included the 6-week Taking Charge of My Life and Health curriculum prior to moving to the mutual help format.24 While this curriculum still informs peer facilitator training, it is not used in new groups. It has anecdotally been reported that this change was positive, but the impact of this adaptation is unknown.

This evaluation cohort was small (16 participants) and initial patient reported and administrative outcomes were inconclusive. However, most veterans who stopped participating in Vet-to-Vet spoke fondly of their experiences with the program.

CONCLUSIONS

Vet-to-Vet is a promising new initiative to support self-management and social connection in chronic pain care. The program employs a mutual help approach and storytelling to empower veterans living with chronic pain. The effectiveness of these strategies will be evaluated, which will inform its continued growth. The program's current goals focus on sustainment at existing sites and expansion to new sites to reach more rural veterans across the VA enterprise. While Vet-to-Vet is designed to serve those who experience chronic pain, a partnership with the Office of Whole Health has established goals to begin expanding this model to other chronic conditions in 2026.