Whipple Disease With Central Nervous System Involvement

Background: Whipple disease is a rare, chronic, and systemic infectious disease caused by the bacterium Tropheryma whipplei. It can be mistaken for numerous other diseases, including seronegative rheumatoid arthritis and tropical sprue, and it is known to occur concurrently with giardiasis. Whipple disease can be fatal if not promptly recognized and treated.

Case Presentation: A 53-year-old male presented with an 8-month history of persistent diarrhea, memory distortion, visual disturbances, 30-lb weight loss, and intermittent bilateral hand and knee arthralgias. An autoimmune evaluation for arthralgia was negative. Polymerase chain reaction testing of duodenal biopsy tissue and cerebrospinal fluid was positive for Tropheryma whipplei.

Conclusions: Whipple disease should be considered in the differential diagnosis when patients present with chronic seronegative arthritis, gastrointestinal abnormalities, and cognitive changes. This case, along with others reported in the literature, point to the importance of additional testing for Whipple disease, even when a concurrent infection, such as giardiasis, has been identified.

Whipple disease is a chronic, rare, infectious disease that manifests with systemic symptoms. This disease is caused by the gram-positive bacterium Tropheryma whipplei (T. whipplei). Common manifestations include gastrointestinal symptoms indicative of malabsorption, such as chronic diarrhea, unintentional weight loss (despite normal nutrient intake), and greasy, voluminous, foul-smelling stool. Other, less common manifestations include cardiovascular, endocrine, musculoskeletal, neurologic, and renal signs and symptoms. The prevalence of the disease is rare, affecting 3 in 1 million patients.1 This case highlights the importance of considering Whipple disease when treating patients with multiple symptoms and concurrent disease processes.

Case Presentation

A 53-year-old male with a medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hypothyroidism, and microcytic anemia presented with an 8-month history of persistent diarrhea associated with abdominal bloating, abdominal discomfort, and a 30-lb weight loss. He also reported fatigue, headaches, inability to concentrate, memory distortion, and visual disturbances involving flashes and floaters. The patient reported no fever, chills, nuchal rigidity, or prior neurologic symptoms. He reported intermittent bilateral hand and knee arthralgias. An autoimmune evaluation for arthralgia was negative, and a prior colonoscopy had been normal.

The patient’s hobbies included gardening, hiking, fishing, and deer hunting in Wyoming and Texas. He had spent time around cattle, dogs, and cats. He consumed alcohol twice weekly but reported no tobacco or illicit drug use or recent international travel. The patient’s family history was positive for rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension.

The patient’s vital signs were all within reference ranges, and lung auscultation revealed clear breathing sounds with no cardiac murmurs, gallops, or rubs. An abdominal examination revealed decreased bowel sounds, while the rest of the physical examination was otherwise normal.

Initial laboratory results showed that his sodium was 134 mEq/L (reference range, 136-145 mEq/L), hemoglobin was 9.3 g/dL (reference range for men, 14.0-18.0 g/dL), and hematocrit was 30.7% (reference range for men 42%-52%). His white blood cell (WBC) count and thyroid-stimulating hormone level were within normal limits. A cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed the following: WBCs 1.0/μL (0-5/μL), segmented neutrophils 10% (reference range, 7%), lymphocytes 80% (reference range, 40-80%), macrophages 10% (reference range, 2%), red blood cells 3 × 106 /μL (reference range, 4.3- 5.9 × 106 /µL), protein 23.5 mg/dL (reference range, 15-60 mg/dL), and glucose 44 mg/dL (reference range, 50-80 mg/dL).

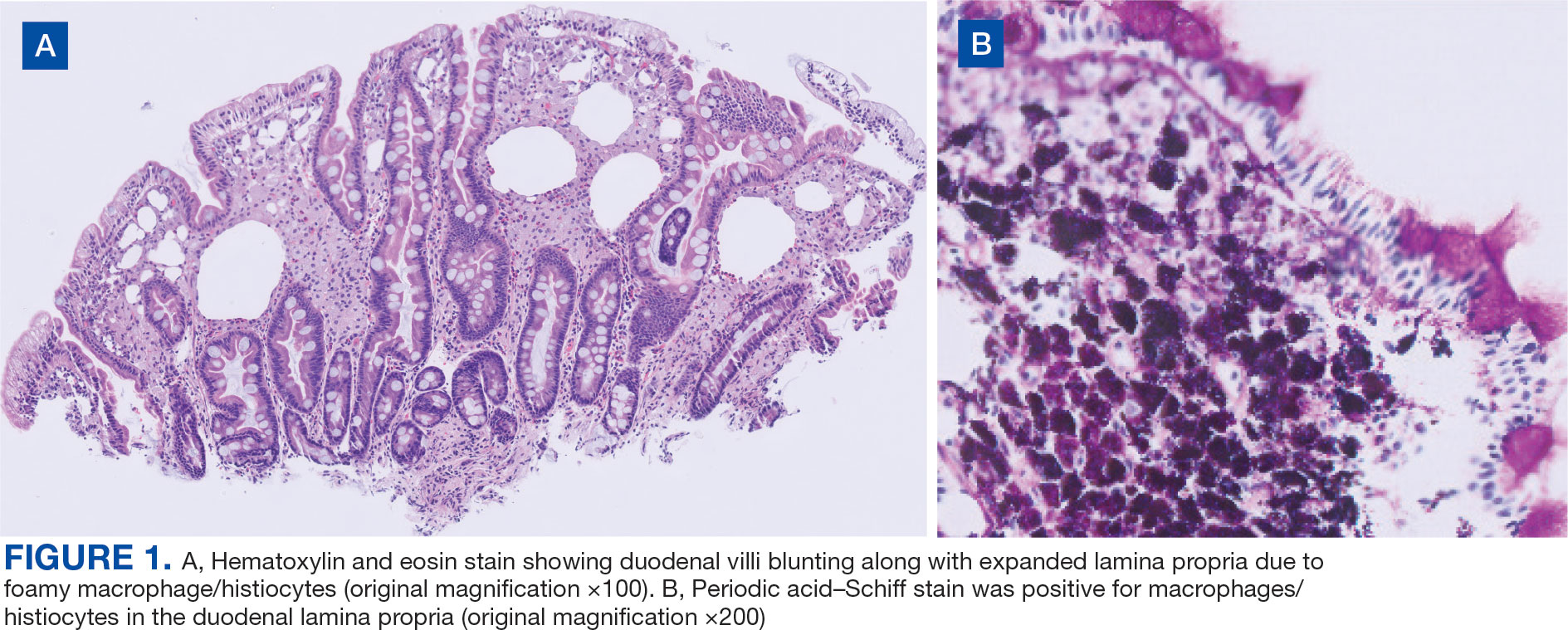

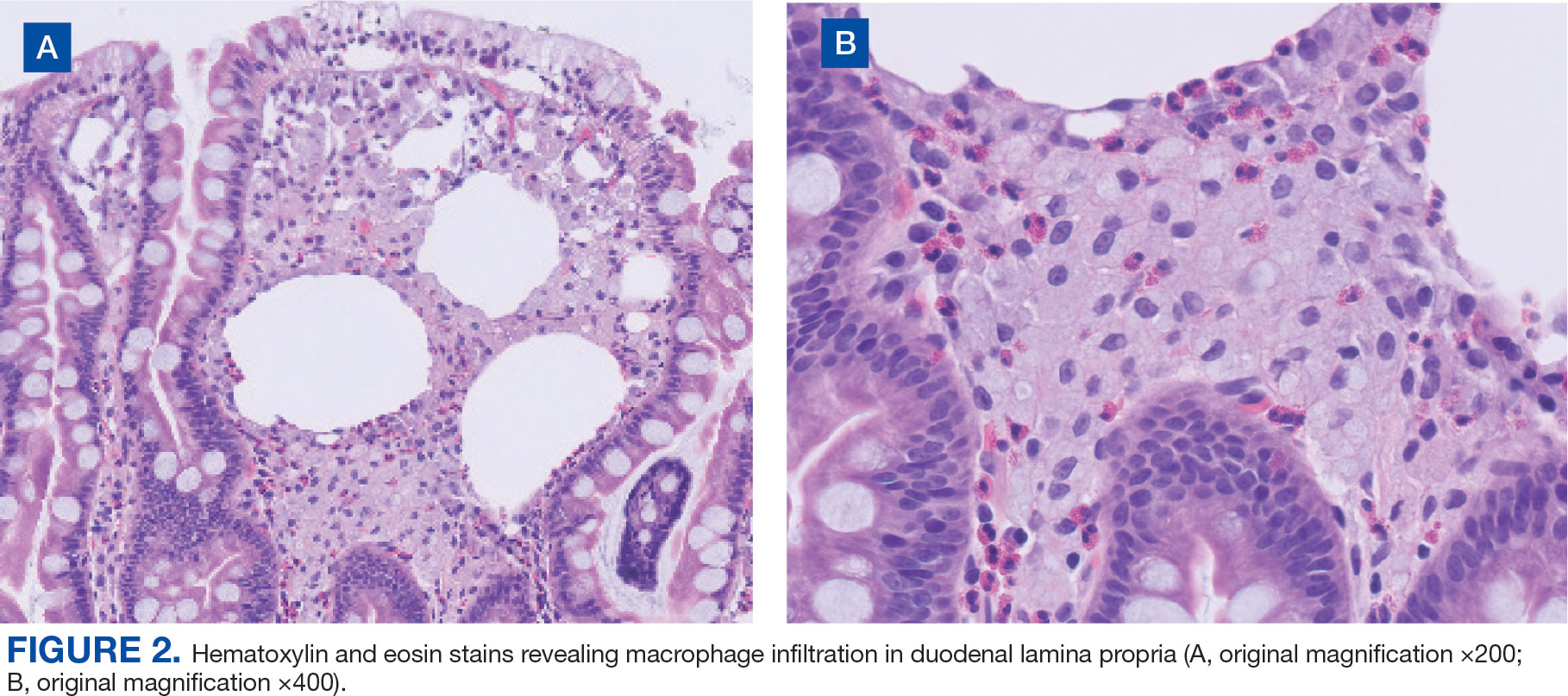

Upper endoscopy with duodenal biopsy showed benign duodenal mucosa. Histopathologic evaluation revealed abundant foamy macrophages within lamina propria. Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stain was positive, diastase-resistant material was visualized within the macrophages (Figures 1 and 2). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of duodenal biopsy tissue was positive for T. whipplei. A lumbar puncture was performed, and PCR testing of CSF for T. whipplei was also positive. A stool PCR test was positive for Giardia. Transthoracic echocardiogram and brain magnetic resonance imaging were normal.

We treated the patient’s giardiasis with a single dose of oral tinidazole 2 g. To treat Whipple disease with central nervous system (CNS) involvement, we started the patient on ceftriaxone 2 g intravenous every 24 hours for 4 weeks, followed by oral trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole (TMPSMX) 160/800 mg twice daily with an expected 1-year course.

Two months into TMP-SMX therapy, the patient developed an acute kidney injury with hyperkalemia (potassium, 5.5 mEq/L). We transitioned the therapy to doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg orally 3 times daily to complete 18 months of therapy. A lumbar puncture for CSF PCR and duodenal biopsy was planned for 6 months and 1 year after diagnosis.

Discussion

Whipple disease is often overlooked when making a diagnosis due to the nonspecific nature of its associated signs and symptoms. Classic Whipple disease has 2 stages: an initial prodromal stage marked by intermittent arthralgias, followed by a second gastrointestinal stage that involves chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain, and weight loss.1-3 Infection can sometimes be misdiagnosed as seronegative rheumatoid arthritis and a definite diagnosis can be missed for extended periods, with 1 case taking up to 8 years to diagnose after the first joint manifestations.2,4,5 Blood culture-negative endocarditis has also been well documented.1-5

The most common CNS clinical manifestations of Whipple disease include cognitive changes (eg, dementia), ocular movement disturbances (eg, oculomasticatory myorhythmia, which is pathognomonic for Whipple disease), involuntary movements, and hypothalamic dysfunction.1,6 Other neurologic symptoms include seizures, ataxia, meningitis, and myelopathy. Cerebrospinal fluid studies vary, with some results being normal and others revealing elevated protein counts.1

Disease Course

A retrospective study by Compain and colleagues reports that Whipple disease follows 3 patterns of clinical CNS involvement: classic Whipple disease with neurologic involvement, Whipple disease with isolated neurologic involvement, and neurologic relapse of previously treated Whipple disease.6 Isolated neurologic involvement is roughly 4% to 8%.6-8 Previous studies showed that the average delay from the presentation of neurologic symptoms to diagnosis is about 30 months.9

Diagnosis can be made with histologic evaluation of duodenal tissue using hematoxylin-eosin and PAS stains, which reveal foamy macrophages in expanded duodenal lamina propria, along with a positive tissue PCR.1,5 The slow replication rate of T. whipplei limits the effectiveness of bacterial cultures. After adequate treatment, relapses are still possible and regularly involve the CNS.1,4

Treatment typically involves blood-brain barrier-crossing agents, such as 2 weeks of meropenem 1 g every 24 hours or 2 to 4 weeks of ceftriaxone 2 g every 24 hours, followed by 1 year of TMP-SMX 160/800 mg twice daily. Doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg orally 3 times daily have also been shown to be effective, as seen in our patient.

Mortality rates vary for patients with Whipple disease and CNS involvement. One study reported poor overall prognosis in patients with CNS involvement, with mortality rates as high as 27%.10 However, rates of early detection and appropriate treatment may be improving, with 1 case series reporting 11% mortality in 18 patients with Whipple disease.6

Diagnosis

Because Whipple disease mimics many other diseases, misdiagnosis as infectious and noninfectious etiologies is common. PAS stain and tissue PCR helped uncover Whipple disease in a patient erroneously diagnosed with refractory Crohn disease.11

Weight loss, diarrhea, arthralgias, and cognitive impairment can also be seen in celiac disease. However, dermatologic manifestations, metabolic bone disease, and vitamin deficiencies are characteristics of celiac disease and can help distinguish it from T. whipplei infection.12

Whipple disease can also be mistaken for tropical sprue. Both can manifest with chronic diarrhea and duodenal villous atrophy; however, tropical sprue is more prevalent in specific geographic areas, and clinical manifestations are primarily gastrointestinal. Weight loss, diarrhea, steatorrhea, and folate deficiency are unique findings in tropical sprue that help differentiate it from Whipple disease.13 Likewise, other infectious diseases can be misdiagnosed as Whipple disease. Duodenal villi blunting and positive PAS staining have been reported in a Mycobacterium avium complex intestinal infection in a patient with AIDS, leading to a misdiagnosis of Whipple disease.14

Some parasitic infections have gastrointestinal symptoms similar to those of Whipple disease and others, such as giardiasis, are known to occur concurrently with Whipple disease.15-17 Giardiasis can also account for weight loss, malabsorptive symptoms, and greasy diarrhea. One case report hypothesized that 1 disease may predispose individuals to the other, as they both affect villous architecture.17 Additional research is needed to determine where the case reports have left off and to explore the connection between the 2 conditions.

Conclusions

The diagnosis of Whipple disease is challenging and frequently missed due to the rare and protean nature of the disease. This case highlights the importance of clinical suspicion for Whipple disease, especially in patients presenting with chronic seronegative arthritis, gastrointestinal abnormalities, and cognitive changes. Furthermore, this case points to the importance of additional testing for Whipple disease, even when a concurrent infection, such as giardiasis, has been identified.