Lipoprotein(a) Elevation: A New Diagnostic Code with Relevance to Service Members and Veterans

Newly recognized as a clinical diagnosis, Lp(a) elevation is a major contributor to cardiovascular disease risk should be considered for patients with advanced premature atherosclerosis on imaging or a family history of premature cardiovascular disease, particularly when there are few traditional risk factors.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of global mortality. In 2015, 41.5% of the US population had at least 1 form of CVD and CVD accounted for nearly 18 million deaths worldwide.1,2 The major disease categories represented include myocardial infarction (MI), sudden death, strokes, calcific aortic valve stenosis (CAVS), and peripheral vascular disease.1,2 In terms of health care costs, quality of life, and caregiver burden, the overall impact of disease prevalence continues to rise.1,3-6 There is an urgent need for more precise and earlier CVD risk assessment to guide lifestyle and therapeutic interventions for prevention of disease progression as well as potential reversal of preclinical disease. Even at a young age, visible coronary atherosclerosis has been found in up to 11% of “healthy” active individuals during autopsies for trauma fatalities.7,8

The impact of CVD on the US and global populations is profound. In 2011, CVD prevalence was predicted to reach 40% by 2030.9 That estimate was exceeded in 2015, and it is now predicted that by 2035, 45% of the US population will suffer from some form of clinical or preclinical CVD. In 2015, the decadeslong decline in CVD mortality was reversed for the first time since 1969, showing a 1% increase in deaths from CVD.1 Nearly 300,000 of those using US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) services were hospitalized for CVD between 2010 and 2014.10 The annual direct and indirect costs related to CVD in the US are estimated at $329.7 billion, and these costs are predicted to top $1 trillion by 2035.1 Heart attack, coronary atherosclerosis, and stroke accounted for 3 of the 10 most expensive conditions treated in US hospitals in 2013.11 Globally, the estimate for CVD-related direct and indirect costs was $863 billion in 2010 and may exceed $1 trillion by 2030.12

The nature of military service adds additional risk factors, such as posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, sleep disorders and physical trauma which increase CVD morbidity/ mortality in service members, veterans, and their families.13-16 In addition, living in lowerincome areas (countries or neighborhoods) can increase the risk of both CVD incidence and fatalities, particularly in younger individuals.17-20 The Military Health System (MHS) and VA are responsible for the care of those individuals who have voluntarily taken on these additional risks through their time in service. This responsibility calls for rapid translation to practice tools and resources that can support interventions to minimize as many modifiable risk factors as possible and improve longterm health. This strategy aligns with the World Health Organization’s (WHO) focus on prevention of disease progression through interventions targeting modifiable risk.3-6,21-23 The driving force behind the launch of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Million Hearts program was the goal of preventing 1 million heart attacks and strokes by 2017 with risk reduction through aspirin, blood pressure control, cholesterol management, smoking cessation, sodium reduction, and physical activity.24,25 While some reductions in CVD events have been documented, the outcomes fell short of the goals set, highlighting both the need and value of continued and expanded efforts for CVD risk reduction.26

More precise assessment of risk factors during preventative care, as well as after a diagnosis of CVD, may improve the timeliness and precision of earlier interventions (both lifestyle and therapeutic) that reduce CVD morbidity and mortality.27 Personalized or precision medicine approaches take into account differences in socioeconomic, environmental, and lifestyle factors that are potentially reversible, as well as gender, race, and ethnicity.28-31 Current methods of predicting CVD risk have considerable room for improvement.27 About 40% of patients with newly diagnosed CVD have normal traditional cholesterol profiles, including those whose first cardiac event proves fatal.29-33 Currently available risk scores (hundreds have been described in the literature) mischaracterize risk in minority populations and women, and have shown deficiencies in identifying preclinical atherosclerosis.34,35 The failure to recognize preclinical CVD in military personnel during their active duty life cycle results in missed opportunities for improved health and readiness sustainment.

Most CVD risk prediction models incorporate some form of blood lipids. Total cholesterol (TC) is most commonly used in clinical practice, along with high-density lipoprotein (HDLC), low-density lipoprotein (LDLC), and triglycerides (TG).23,27,36 High LDLC and/or TC are well established as lipid-related CVD risk factors and are incorporated into many CVD risk scoring systems/models described in the literature.27 LDLC reduction is commonly recommended as CVD prevention, but even with optimal statin treatment, there is still considerable residual risk for new and recurrent CVD events.28,32,34,35,37-42

Incorporating novel biomarkers and alternative lipid measurements may improve risk prediction and aid targeted treatment, ultimately reducing CVD events.27 Apolipoprotein B (ApoB) is a major atherogenic component embedded in LDL and VLDL correlating to non-HDLC and may be useful in the setting of triglycerides ≥ 200 mg/d as levels > 130 mg/ dL appear to be risk-enhancing, but measurements may be unreliable.43 According to the 2018 Cholesterol Guidelines, lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] elevation also is recognized as a risk-enhancing factor that is particularly implicated when there is a strong family history of premature atherosclerotic CVD or personal history of CVD not explained by major risk factors.43

Lp(a) elevation is a largely underrecognized category of lipid disorder that impacts up to 20% to 30% of the population globally and within the US, although there is considerable variability by geographic location and ethnicity.44 Globally, Lp(a) elevation places > 1 billion people at moderate to high risk for CVD.44 Lp(a) has a strong genetic component and is recognized as a distinct and independent risk factor for MI, sudden death, strokes and CAVS. Lp(a) has an extensive body of evidence to support its distinct role both as a causal factor in CVD and as an augmentation to traditional risk factors.44-48

Lipoproteni(a) Elevation Use For Diagnosis

The importance of Lp(a) elevation as a clinical diagnosis rather than a laboratory abnormality alone was brought forward by the Lipoprotein(a) Foundation. Its founder, Sandra Tremulis, is a survivor of an acute coronary event that occurred when she was 39-years old, despite running marathons and having none of the traditional CVD lifestyle risk factors.49 This experience inspired her to create the Lipoprotein(a) Foundation to give a voice to families living with or at risk for CVD due to Lp(a) elevation.

As often happens in the progress of medicine, patients and their families drive change based on their personal experiences with the gaps in standard clinical practice. It was this foundation—not a member of the medical establishment—that submitted the formal request for the addition of new ICD-10-CM diagnostic and family history codes for Lp(a) elevation during the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) September 2017 ICD-10-CM Coordination and Maintenance Committee meeting.50 In June 2018, the final ICD-10-CM code addenda for 2019 was released and included the new codes E78.41 (Elevated Lp[a]) and Z83.430 (Family history of elevated Lp[a]).52 After the new codes were approved, both the American Heart Association and the National Lipid Association added recommendations regarding Lp(a) testing to their clinical practice guidelines.43,52

Practically, these codes standardize billing and payment for legitimate clinical work and laboratory testing. Prior to the addition of Lp(a) elevation as a clinical diagnosis, testing and treatment of Lp(a) elevation was considered experimental and not medically necessary until after a cardiovascular event had already occurred. Services for Lp(a) elevation were therefore not reimbursed by many healthcare organizations and insurance companies. The new ICD-10-CM codes encourage the assessment of Lp(a) both in individuals with early onset major CVD events and in presumably fit, healthy individuals, particularly when there is a family history of Lp(a) elevation. Given that Lp(a) levels do not change significantly over time, the current understanding is that only a single measurement is needed to define the individual risk over a lifetime.41,42,44,45 As therapies targeting Lp(a) levels evolve, repeated measurements may be indicated to monitor response and direct changes in management. “Elevated Lipoprotein(a)” is the first laboratory testing abnormality that has achieved the status of a clinical diagnosis.

Lp(a) Measurements

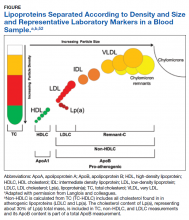

There is considerable complexity to the measurement of lipoproteins in blood samples due to heterogeneity in both density and size of particles as illustrated in the Figure.53

For traditional lipids measured in clinical practice, the size and density ranges from small high-density lipoprotein (HDL) through LDLC and intermediate- density lipoprotein (IDL) to the largest least dense particles in the very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) and chylomicron remnant fractions. Standard lipid profiles consist of mass concentration measurements (mg/dL) of TC, TG, HDLC, and LDLC.53 Non-HDLC (calculated as: TC−HDLC) consists of all cholesterol found in atherogenic lipoproteins, including remnant-C and Lp(a). Until recently, the cholesterol content of Lp(a), corresponding to about 30% of Lp(a) total mass, was included in the TC, non-HDLC and LDLC measurements with no separate reporting by the majority of clinical laboratories.

After > 50 years of research on the structure and biochemistry of Lp(a), the physiology and biological functions of these complex and polymorphic lipoprotein particles are not fully understood. Lp(a) is composed of a lipoprotein particle similar in composition to LDL (protein and lipid), containing 1 molecule of ApoB wrapped around a core of cholesteryl ester and triglyceride with phospholipids and unesterified cholesterol at its surface.48 The presence of a unique hydrophilic, highly glycosylated protein referred to as apolopoprotienA (apo[a]), covalently attached to ApoB-100 by a single disulfide bridge, differentiates Lp(a) from LDL.48 Cholesterol rich ApoB is an important component within many lipoproteins pathogenic for atherosclerosis and CVD.45,47,53

The apo(a) contributes to the increased density of Lp(a) compared to LDLC with associated reduced binding affinity to the LDL receptor. This reduced receptor binding affinity is a presumed mechanism for the lack of Lp(a) plasma level response to statin therapies, which increase hepatic LDL receptor activity.47 Apo(a) evolved from the plasminogen gene through duplication and remodeling and demonstrates extensive heterogeneity in protein size, with > 40 different apo(a) isoforms resulting in > 40 different Lp(a) particle sizes. Size of the apo(a) particle is determined by the number of pleated structures known as kringles. Most people (> 80%) carry 2 different-sized apo(a) isoforms. Plasma Lp(a) level is determined by the net production of apo(a) in each isoform, and the smaller apo(a) isoforms are associated with higher plasma levels of Lp(a).45

Given the heterogeneity in Lp(a) molecular weight, which can vary even within individuals, recommendations have been made for reporting results as particle numbers or concentrations (nmol/L or mmol/L) rather than as mass concentration (mg/dL).55 However, the majority of the large CVD morbidity and mortality outcomes studies used Lp(a) mass concentration levels in mg/ dL to characterize risk levels.56,57 There is no standardized method to convert Lp(a) measurements from mg/dL to nmol/L.55 Current assays using WHO standardized reagents and controls are reliable for categorizing risk levels.58

The European Atherosclerosis Society consensus panel recommended that desirable Lp(a) levels should be below the 80th percentile (< 50 mg/dL or < 125 nmol/L) in patients with intermediate or high CVD risk.59 Subsequent epidemiological and Mendelian randomization studies have been performed in general populations with no history of CVD and demonstrated that increased CVD risk can be detected with Lp(a) levels as low as 25 to 30 mg/dL.56,60-63 In secondary prevention populations with prior CVD and optimal treatment (statins, antiplatelet drugs), recurrent event risk was also increased with elevated Lp(a).63-66

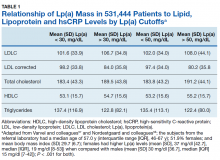

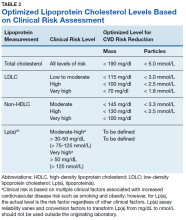

Using immunoturbidometric assays, Varvel and colleagues reported the prevalence of elevated Lp(a) mass concentration levels (mg/dL) in > 500,000 US patients undergoing clinical evaluations based on data from a referral laboratory of patients.58 The mean Lp(a) levels were 34.0 mg/dL with median (interquartile range [IQR]) levels at 17 (7-47) mg/dL and overall range of 0 to 907 mg/dL.58 Females had higher Lp(a) levels compared to males but no ethnic or racial breakdown was provided. Lp(a) levels > 30 mg/dL and > 50 mg/dL were present in 35% and 24% of subjects, respectively. Table 1 displays the relationship between various Lp(a) level cut-offs to mean levels of LDLC, estimated LDLC corrected for Lp(a), TC, HDLC, and TG.58 The data demonstrate that Lp(a) elevation cannot be inferred from LDLC levels nor from any of the other traditional lipoprotein measures. Patients with high risk Lp(a) levels may have normal LDLC. While Lp(a) thresholds have been identified for stratification of CVD risk, the target levels for risk reduction have not been specifically defined, particularly since therapies are not widely available for reduction of Lp(a). Table 2 provides an overview of clinical lipoprotein measurements that may be reasonable targets for therapeutic interventions and reduction of CVD risk.44,53,55 In general, existing studies suggest that radical reduction (> 80%) is required to impact long-term outcomes, particularly in individuals with severe disease.68,69

LDLC reduction alone leaves a residual CVD risk that is greater than the risk reduced.40 In addition, the autoimmune inflammation and lipid specific autoantibodies play an important role in increased CVD morbidity and mortality risk.70,71 The presence of autoantibodies such as antiphospholipid antibodies (without a specific autoimmune disease diagnosis) increases the risk of subclinical atherosclerosis.72,73 Certain autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus are recognized as independent risk factors for CVD.74,75 Autoantibodies appear to mediate CVD events and mortality risk, independent of traditional therapies for risk reduction.73 Further research is needed to clarify the role of autoantibodies as markers of increased or decreased CVD risk and their mechanism of action.

Autoantibodies directed at new antigens in lipoproteins within atherosclerotic lesions can modulate the impact of atherosclerosis via activation of the innate and adaptive immune system.76 The lipid-associated neopeptides are recognized as damage-associated or danger- associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), also known as alarmins, which signal molecules that can trigger and perpetuate noninfectious inflammatory responses.77-79 Plasma autoantibodies (immunoglobulin M and G [IgM, IgG]) modify proinflammatory oxidation-specific epitopes on oxidized phospholipids (oxPL) within lipoproteins and are linked with markers of inflammation and CVD events.80-82 Modified LDLC and ApoB-100 immune complexes with specific autoantibodies in the IgG class are associated with increased CVD.76 These and other risk-modulating autoantibodies may explain some of the variability in CVD outcomes by ethnicity and between individuals.

Some antibodies to oxidized LDL (ox-LDL) may have a protective role in the development of atherosclerosis.83,84 In a cohort of > 500 women, the number of carotid atherosclerotic plaques and total carotid plaque area were inversely correlated with a specific IgM autoantibody (MDA-p210).84 High concentrations of Lp(a)- containing circulating immune complexes and Lp(a)-specific IgM and IgG have been described in patients with coronary heart disease (CHD).85 Like ox-LDL, oxidized Lp(a) [ox-Lp(a)] is more potent than native Lp(a) in increasing atherosclerosis risk and is increased in patients with CHD compared to healthy controls.86-88 Ox-Lp(a) levels may represent an even stronger risk marker for CVD than ox-LDL.85

Possible Mechanisms of Pathogenesis

While the precise quantification of Lp(a) in human plasma (or serum) has been challenging, current clinical laboratories use standardized international reference reagents and controls in their assays. Most current Lp(a) assays are based on immunological methods (eg, immunonephelometry, immunoturbidimetry, or enzyme linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA]) using antibodies against apo(a).89 Apo(a) contains 10 subtypes of kringle IV and 1 copy of kringle V. Some assays use antibodies against kringle-IV type 2; however, it has been recommended that newer methods should use antibodies against the specific bridging kringle-IV Type 9 domain, which has a more stable bond and is present as a single copy.48,89 Other approaches to Lp(a) measurement include ultraperformance liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry that can determine both the concentration and particle size of apo(a).48,90 For routine clinical care, currently available assays reporting in mg/dL can be considered fairly accurate for separating low-risk from moderate-to-high-risk patients.45

The physiologic role of Lp(a) in humans remains to be fully defined and individuals with extremely low plasma Lp(a) levels present no disease or deficiency syndromes.91 Lp(a) accumulates in endothelial injuries and binds to components of the vessel wall and subendothelial matrix, presumably due to the strong lysine binding site in apo(a).46 Mediated by apo(a), the binding stimulates chemotactic activation of monocytes/macrophages and thereby modulating angiogenesis and inflammation.89 Lp(a) may contribute to CVD and CAVS via its LDL-like component, with proinflammatory effects of oxidized phospholipids (OxPL) on both ApoB and apo(a) and antifibrinolytic/prothrombotic effects of apo(a).92 In Vitro studies have demonstrated that apo(a) modifies cellular function of cultured vascular endothelial cells (promoting stress fiber formation, endothelial contraction and vascular permeability), smooth muscles, and monocytes/ macrophages (promoting differentiation of proinflammatory M1-1 type macrophages) via complex mechanisms of cell signaling and cytokine production.89 Lp(a) is the only monogenetic risk factor for aortic valve calcification and stenosis93 and is strongly linked specifically with the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs10455872 in the gene LPA encoding for apo(a).94

CVD Risk Predictive Value

There are a large number of studies demonstrating that Lp(a) elevations are an independent predictor of adverse cardiovascular outcomes including MI, sudden death, strokes, calcific aortic valve stenosis and peripheral vascular disease (Table 3). The Copenhagen City Heart Study and Copenhagen General Population Study are well known prospective population- based cohort studies that track outcomes through national patient registries.95 These studies demonstrate increased risk for MI, CHD, CAVS, and heart failure when subjects with very high Lp(a) levels (50-115 mg/dL) are compared with subjects with very low Lp(a) levels (< 5 mg/dL).96-100 Subjects with less extreme Lp(a) elevations (> 30 mg/dL) also show increased risk of CVD when they have comorbid LDLC elevations.101 However, the Copenhagen studies are composed exclusively of white subjects and the effects of Lp(a) are known to vary with race or ethnicity.

The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) recruited an ethnically diverse sample of > 6,000 Americans, aged 45 to 84 years, without CVD, into an ongoing prospective cohort study. Research using subjects from this study has found consistently increased risk of CHD, heart failure, subclinical aortic valve calcification, and more severe CAVS in white subjects with elevated Lp(a).60,102,103 Black subjects with elevated Lp(a) had increased risk of CHD and more severe CAVS and Hispanic subjects with Lp(a) elevation were at higher risk for CHD.60,102 So far, no studies of MESA subjects have identified a relationship between Lp(a) elevation and CVD events for Asian-Americans subjects (predominantly of Chinese descent). There is a need for ongoing research to more precisely define relevant cut-off levels by race, ethnicity and sex.

The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study was a prospective multiethnic cohort study including > 15,000 US adults, aged 45 to 64 years.103 Lp(a) elevations in this cohort were associated with greater risks for first CVD events, heart failure, and recurrent CVD events.61,64,105 The risk of stroke for subjects with elevated Lp(a) was greater for black and white women, and for black men.61,106 However, a meta-analysis of case-control studies showed increased ischemic stroke risk in both men and women with elevated Lp(a).57

A recent European meta-analysis collected blood samples and outcome data from > 50,000 subjects in 7 prospective cohort studies. Using a central laboratory to standardize Lp(a) measurements, researchers found increased risk of major coronary events and new CVD in subjects with Lp(a) > 50 mg/dL compared to those below that threshold.107

Although many of these studies show modest increases in risk of CVD events with Lp(a) elevation, it should be noted that other studies do not demonstrate such consistent associations. This is particularly true in studies of women and nonwhite ethnic groups.103,108-112 The variability of study results may be due to other confounding factors such as autoantibodies that either upregulate or downregulate atherogenicity of LDLC and potentially other lipoproteins. This is particularly relevant to women who have an increased risk for autoimmune disease.

Lp(a) has significant genetic heritability—75% in Europeans and 85% in African Americans.113 In whites, the LPA gene on chromosome 6p26- 27 with the polymorphism genetic variants rs10455872 and rs3798220 is consistently associated with elevated Lp(a) levels.63,100,113 However, the degree of Lp(a) elevation associated with these specific genetic variants varies by ethnicity.78,113,115

Lifestyle and Cardiovascular Health

It is noteworthy that the Lp(a) genetic risks can also be modified by lifestyle risk reduction even in the absence of significant blood level reductions. For example, Khera and colleagues constructed a genetic risk profile for CVD that included genes related to Lp(a).116 Subjects with high genetic risk were more likely to experience CVD events compared with subjects with low genetic risk. However, risks for CVD were attenuated by 4 healthy lifestyle factors: current nonsmoker, body mass index < 30, at least weekly physical activity, and a healthy diet. Subjects with high genetic risk and an unhealthy lifestyle (0 or 1 of the 4 healthy lifestyle factors) were the most likely to develop CVD (Hazard ratio [HR], 3.5), but that risk was lower for subjects with healthy (3 or 4 of the 4 healthy lifestyle factors) and intermediate lifestyles (2 of the 4 healthy lifestyle factors) (HR, 1.9 and 2.2, respectively), despite despite high genetic risk for CVD.

While the independent CVD risk associated with elevated Lp(a) does not appear to be responsive to lifestyle risk reduction alone, certainly elevated LDLC and traditional risk factors can increase the overall CVD risk and are worthy of preventive interventions. In particular, inflammation from any source exacerbates CVD risk. Proatherogenic diet, insufficient sleep, lack of exercise, and maladaptive stress responses are other targets for personalized CVD risk reduction. 28,117 Studies of dietary modifications and other lifestyle factors have shown reduced risk of CVD events, despite lack of reduction in Lp(a) levels.119,120 It is noteworthy that statin therapy (with or without ezetimibe) fails to impact CAVS progression, likely because statins either raise or have no effect on Lp(a) levels.92,119

Until recently, there has been no evidence supporting any therapeutic intervention causing clinically meaningful reductions in Lp(a). Table 4 lists major drug classes and their effects on Lp(a) and CVD outcomes; however, a detailed discussion of each of these therapies is beyond the scope of this review. Drugs that reduce Lp(a) by 20-30% have varying effects on CVD outcomes, from no effect122,123 to a 10% to 20% decrease in CVD events when compared with a placebo.124,125 Because these drugs also produce substantial reductions in LDLC, it is not possible to determine how much of the beneficial effects are due to reductions in Lp(a).

Lipoprotein apheresis produces profound reductions in Lp(a) of 60 to 80% in very highrisk populations.69,126 Within-subjects comparisons show up to 80% reductions in CVD events, relative to event rates prior to treatment initiation.69,127 Early trials of antisense oligonucleotide against apo(a) therapies show potential to produce similar outcomes.128,129 These treatments may be particularly effective in patients with isolated Lp(a) elevations.

Summary

Lp(a) elevation is a major contributor to cardiovascular disease risk and has been recognized as an ICD-10-CM coded clinical diagnosis, the first laboratory abnormality to be defined a clinical disease in the asymptomatic healthy young individuals. This change addresses currently under- diagnosed CVD risk independent of LDLC reduction strategies. A brief overview of recent guidelines for the clinical use of Lp(a) testing from the American Heart Association43,151 and the National Lipid Association52 can be found in Table 5. Although drug therapies for lowering Lp(a) levels remain limited, new treatment options are actively being developed.

Many Americans with high Lp(a) have not yet been identified. Expanded one-time screening can inform these patients of their cardiovascular risk and increase their access to early, aggressive lifestyle modification and optimal lipid-lowering therapy. Given the further increased CVD risk factors for military service members and veterans, a case can be made for broader screening and enhanced surveillance of elevated Lp(a) in these presumably healthy and fit individuals as well as management focused on modifiable risk factors.

Acknowledgements

This program initiative was conducted by the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc. as part of the Integrative Cardiac Health Project at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC), and is made possible by a cooperative agreement that was awarded and administered by the US Army Medical Research & Materiel Command (USAMRMC), at Fort Detrick under Contract Number: W81XWH-16-2-0007. It reflects literature review preparatory work for a research protocol but does not involve an actual research project. The work in this manuscript was supported by the staff of the Integrative Cardiac Health Project (ICHP) with special thanks to Claire Fuller, Elaine Walizer, Dr. Mariam Kashani and the entire health coaching team.