How to better identify and manage women with elevated breast cancer risk

This case-based review details screening and management strategies that can maximize the care you provide to women at heightened risk.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Assess breast cancer risk in all women starting at age 35. C

› Perform enhanced screening in all women with a lifetime risk of breast cancer > 20%. A

› Discuss chemoprevention for all women at elevated risk for breast cancer. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE

Ms. P’s clinician starts with an assessment using the Gail model. However, when the result comes back with average risk, the clinician decides to follow up with the Tyrer-Cuzick model in order to incorporate Ms. P’s multiple second-degree relatives with breast and ovarian cancer. (The BCSC model was not used because it only includes first-degree relatives.)

Genetic testing

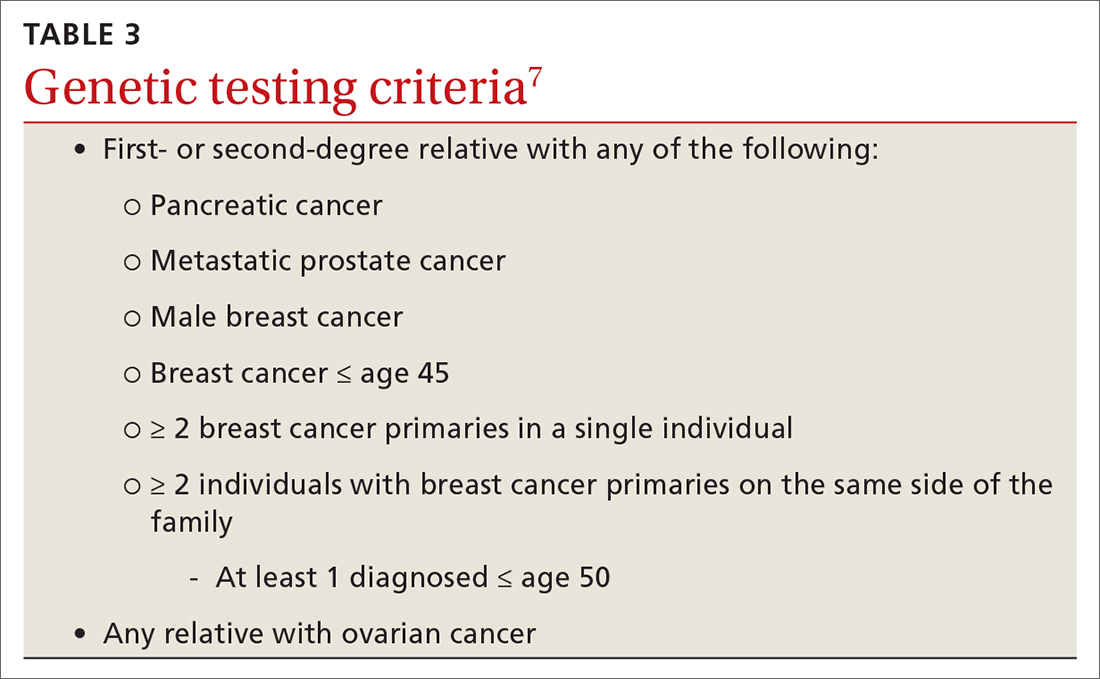

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend genetic testing if a woman has a first- or second-degree relative with pancreatic cancer, metastatic prostate cancer, male breast cancer, breast cancer at age 45 or younger, 2 or more breast cancers in a single person, 2 or more people on the same side of the family with at least 1 diagnosed at age 50 or younger, or any relative with ovarian cancer (see TABLE 3).7 Before ordering genetic testing, it is useful to refer the patient to a genetic counselor for a thorough discussion of options.

Results of genetic testing may include high-risk variants, moderate-risk variants, and variants of unknown significance (VUS), or be negative for any variants. High-risk variants for breast cancer include BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, and cancer syndrome variants such as TP53, PTEN, STK11, and CDH1.5,6,9,13-15 These high-risk variants confer sufficient risk that women with these mutations are automatically categorized in the high-risk group. It is estimated that high-risk variants account for only 25% of the genetic risk for breast cancer.16

BRCA1/2 and PTEN mutations confer greater than 80% lifetime risk, while other high-risk variants such as TP53, CDH1, and STK11 confer risks between 25% and 40%. These variants are also associated with cancers of other organs, depending on the mutation.17

Moderate-risk variants—ATM and CHEK2—do not confer sufficient risk to elevate women into the high-risk group. However, they do qualify these intermediate-risk women to participate in a specialized management strategy.5,9,13,18

VUS are those for which the associated risk is unclear, but more research may be done to categorize the risk.9 The clinical management of women with VUS usually entails close monitoring.

In an effort to better characterize breast cancer risk using a combination of pathogenic variants found in broad multi-gene cancer predisposition panels, researchers have developed a method to combine risks in a “polygenic risk score” (PRS) that can be used to counsel women (see “What is a polygenic risk score for breast cancer?” on page 203).19-21PRS predicts an additional 18% of genetic risk in women of European descent.21

SIDEBAR

What is a polygenic risk score for breast cancer?

- A polygenic risk score (PRS) is a mathematical method to combine results from a variety of different single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs; ie, single base pair variants) into a prediction tool that can estimate a woman’s lifetime risk of breast cancer.

- A PRS may be most accurate in determining risk for women with intermediate pathogenic variants, such as ATM and CHEK2. 19,20

- PRS has not been studied in non-White women.21

Continue to: CASE