Probiotics as a Tx resource in primary care

While probiotics have not been marketed as drugs, clinicians can still recommend them in an evidence-based manner.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Consider specific probiotics to prevent antibioticassociated diarrhea, reduce crying time in colicky infants, and improve therapeutic effectiveness of antibiotics for bacterial vaginosis. A

› Consider specific probiotics to reduce the risk for Clostridioides (formerly Clostridium) difficile infections, to treat acute pediatric diarrhea, and to manage symptoms of constipation. B

› Check a product’s label to ensure that it includes the probiotic’s genus, species, and strains; the dose delivered in colony-forming units through the end of shelf life; and expected benefits C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Taken together, clinical trials have reported more adverse events in the placebo than probiotic group.42 Infection data collected in these trials have been used in subsequent analyses to demonstrate that in some settings, certain probiotics actually reduce the risk of infections. One notable example was a meta-analysis of 37 RCTs that showed that probiotics reduce the incidence of late-onset neonatal sepsis in premature infants.57

At the present time, risk of probiotic use is low but still demands awareness, especially in unusual circumstances such as use in particularly vulnerable patients not yet studied or use of a product with limited available safety data. Any recommended product should be manufactured in compliance with applicable regulatory standards and preferably assured through voluntary quality audits.49

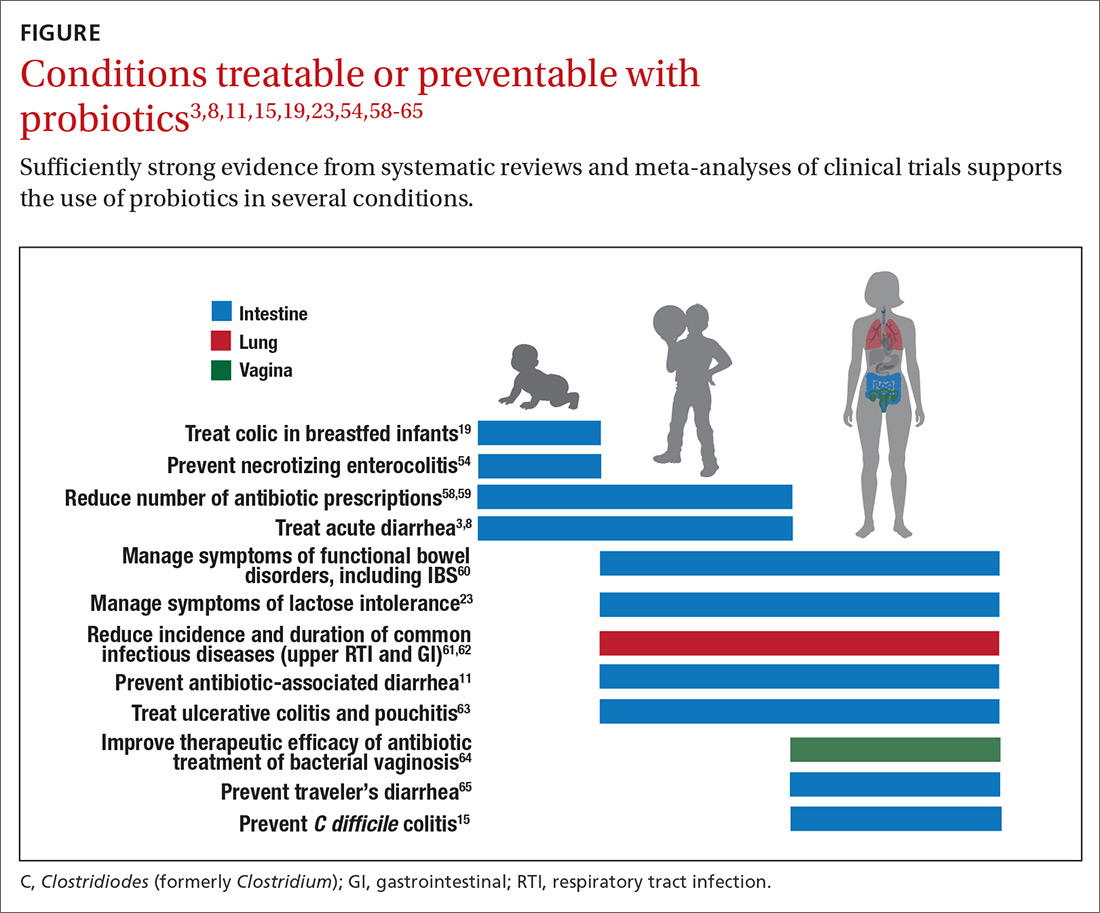

Evidence of effectiveness is strong for many conditions

Probiotics have been studied for clinical benefit in numerous conditions (FIGURE3,8,11,15,19,23,54,58-65), and systematic reviews of the clinical trials have found the overall results to be sufficiently strong to warrant recommendations, even though some individual trials were of low quality.66 Some evidence may require confirmatory studies to clarify which specific product should be recommended.

Admittedly some of the indications are for diseases that most family physicians do not typically manage. For example, the evidence for probiotics for preventing necrotizing enterocolitis in premature infants was reviewed in a Cochrane analysis, which gave an estimated number needed to treat (NNT) of 41 and concluded, “our updated review of available evidence strongly supports a change in practice.”54 A recent study of > 4500 infants in India found a probiotic/prebiotic supplement resulted in a 40% reduction in clinical sepsis compared with placebo.67 Another common use of probiotics is as adjunctive therapy for mild to moderately active ulcerative colitis, where the current estimated NNT is 4.63 Probiotics may also address gut and non-gut conditions and serve different functions throughout the lifespan.

Probiotic applications most relevant to primary care

We summarize in TABLE 13-32 probiotic uses supported by good evidence for indications of general interest in primary care medicine. This table includes endpoints with actionable evidence (including many strength of recommendation taxonomy [SORT] Level 1 studies) that allow us to make strong recommendations. Not all evidence is SORT Grade A, but we agree with the expert groups that deem evidence to be sufficient to warrant recommendations.

Continue to: The granular data...