Limited evidence guides empiric Tx of female chronic pelvic pain

Treat patients based on experience and by applying options used for other chronic pain syndromes. Lifestyle modifications can help, but avoid opioids.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Consider the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device for relief of chronic pelvic pain (CPP) from endometriosis; it’s been found to be more effective than expectant management. B

› Prescribe a trial of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, which was more effective than placebo for CPP for as long as 9 months. B

› Use gabapentin—with or without amitriptyline—to provide greater relief of CPP than amitriptyline alone. B

› Recommend pelvic physical therapy for CPP; the pelvic pain score can be reduced in proportion to the number of sessions. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Treatment

Analgesics

NSAIDs are frequently used as first-line treatment for any kind of pain, including CPP. There is some evidence of benefit from NSAIDs, compared to placebo, in cyclic CPP secondary to dysmenorrhea and endometriosis;5,6 however, evidence of effectiveness in noncyclic CPP is absent. Because of the low cost and availability of NSAIDs, a trial is reasonable as a first-line intervention, particularly in CPP suspected to be endometriosis or of musculoskeletal origin. NSAIDs can cause adverse effects, including nausea, vomiting, headache, and drowsiness in 11% to 14% of women, although these agents are generally well-tolerated on a short-term basis.5

Opioids bind to opioid receptors in the central and peripheral nervous systems, resulting in an analgesic effect. Guidelines issued in 2016 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend safer prescribing through careful evaluation of the risks and benefits of opioids for pain not caused by cancer and for palliation as part of end-of-life care.14

,

The risks of opioid use are well known in the medical community; they include tolerance, physical dependence, misuse, and death, in addition to common adverse effects such as nausea and vomiting, itching, constipation, and fatigue.14,15 Because of those risks and limited long-term benefit in nonmalignant pain disorders, opioid therapy for CPP should be avoided.14 For patients already taking an opioid, discuss a strategy for weaning and, if possible, provide home naloxone therapy in the event of accidental overdose.14

Hormonal therapy

Hormonal therapies are the most common nonsurgical treatment of noncyclic CPP, with or without a definitive diagnosis of endometriosis, in reproductive-age women with CPP.

Combined OCs, despite a lack of quality evidence, are frequently the first hormonal treatment tried in both cyclic and noncyclic CPP. A low-dosage OC may decrease cyclic pain in endometriosis, although it can increase irregular bleeding and nausea.16 As many as 53% of women with CPP reported having undergone a trial of an OC for endometriosis, despite the absence of consistent evidence showing effectiveness in CPP.17

Depot MPA, in trials, decreased pain more than placebo. It can be tried as a treatment, but its use is often limited because of adverse effects, such as weight gain and bloating.8

A trial of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) is supported by moderate-quality evidence for women whose CPP is thought to be a symptom of endometriosis or to have another uterine origin.7

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, such as depot leuprolide and goserelin acetate implant, may be considered in a woman with a diagnosis of endometriosis whose pelvic pain is not alleviated by MPA or an LNG-IUD.9

Nonhormonal therapies

CPP shares pain mechanisms with other pain syndromes, such as neuropathic pain. Antineuropathic medications, such as gabapentin and pregabalin, may, therefore, provide benefit. These medications also produce improvement in pain disorders of the musculoskeletal system, which may contribute to their analgesic effect.18

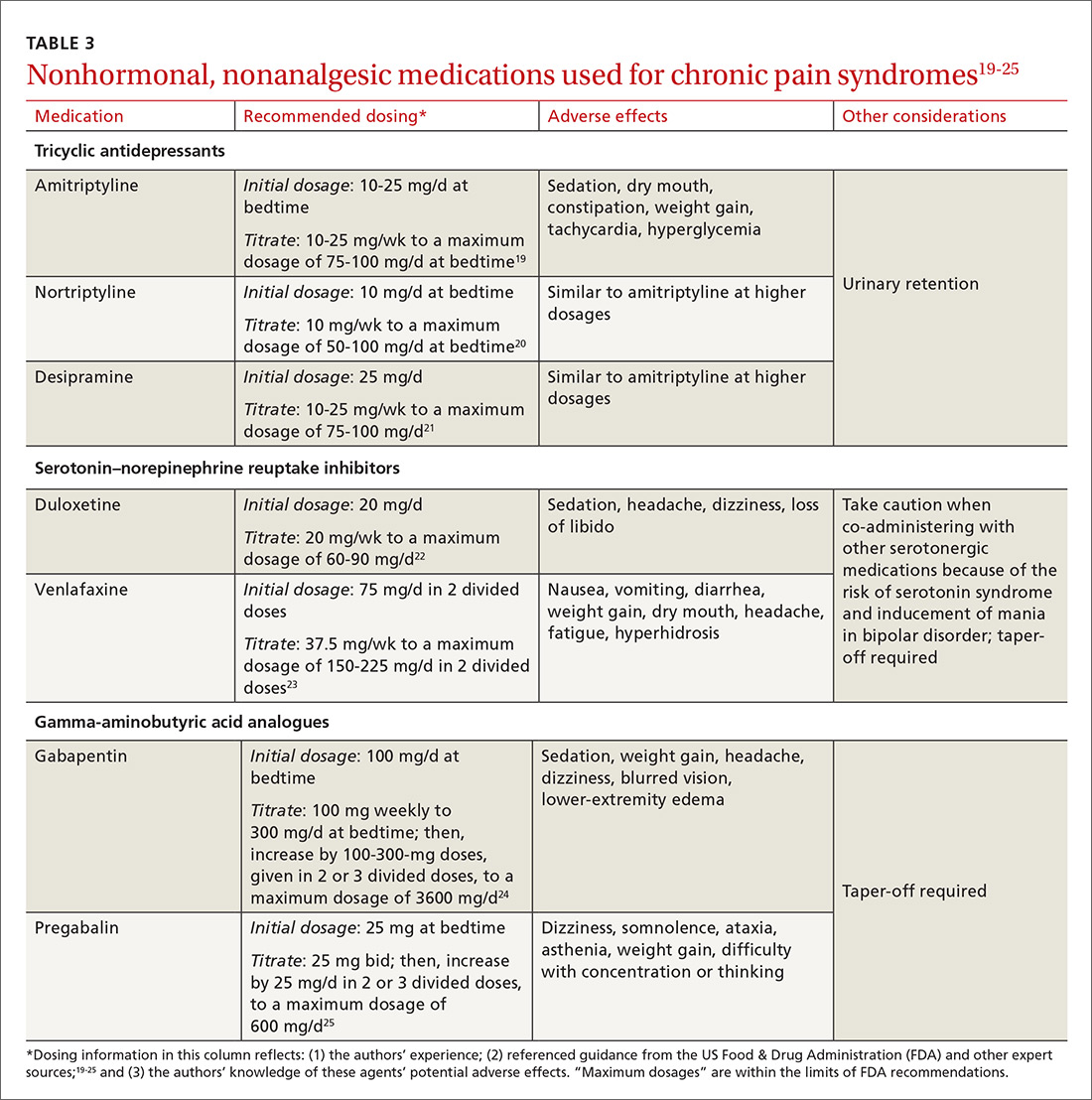

Gabapentin and amitriptyline have been studied in CPP; both were found successful in decreasing perceived pain. Of note, patients who received gabapentin, a gamma-aminobutyric acid analogue, with or without amitriptyline, had more pain relief than those treated with amitriptyline alone.10 Adverse effects of these medications may limit their use (TABLE 319-25).

Tricyclic antidepressants are well-supported, effective treatments for chronic pain through the central increase of norepinephrine. Beginning at a low dosage to diminish adverse effects (TABLE 319-25) and increasing the dosage slowly to an effective level may increase adherence. A trial of at least 6 to 8 weeks, at a moderate dosage, is recommended before discontinuing the medication. Although amitriptyline has the most evidence for value in the management of CPP disorders,10 second-generation tricyclic antidepressants nortriptyline and desipramine have also been used for pain control, and may be better tolerated.

Duloxetine and venlafaxine—serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors—increase serotonin in addition to norepinephrine, which is believed to result in pain control. Although a systematic review of trials of duloxetine for chronic pain showed some improvement in diabetic peripheral neuropathy, fibromyalgia, chronic low back pain, and osteoarthritis, the review excluded CPP in its analysis.26

In our opinion, a selective neurotransmitter reuptake inhibitor can be attempted to diminish the central pain sensitization of CPP. As with all drugs that increase the availability of serotonin, serotonin syndrome is a rare risk. Additionally, when stopping duloxetine, a prolonged taper may be required.