Limited evidence guides empiric Tx of female chronic pelvic pain

Treat patients based on experience and by applying options used for other chronic pain syndromes. Lifestyle modifications can help, but avoid opioids.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Consider the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device for relief of chronic pelvic pain (CPP) from endometriosis; it’s been found to be more effective than expectant management. B

› Prescribe a trial of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, which was more effective than placebo for CPP for as long as 9 months. B

› Use gabapentin—with or without amitriptyline—to provide greater relief of CPP than amitriptyline alone. B

› Recommend pelvic physical therapy for CPP; the pelvic pain score can be reduced in proportion to the number of sessions. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Pelvic floor dysfunction therapy

Pelvic floor dysfunction of the musculature within the bony pelvis may contribute to, or cause, CPP. The pelvic floor musculature may be hypertonic or hypotonic, and trigger points may exist. Despite the frequency of pelvic floor dysfunction, detailed examination of the pelvic floor is not routinely performed during a pelvic exam.

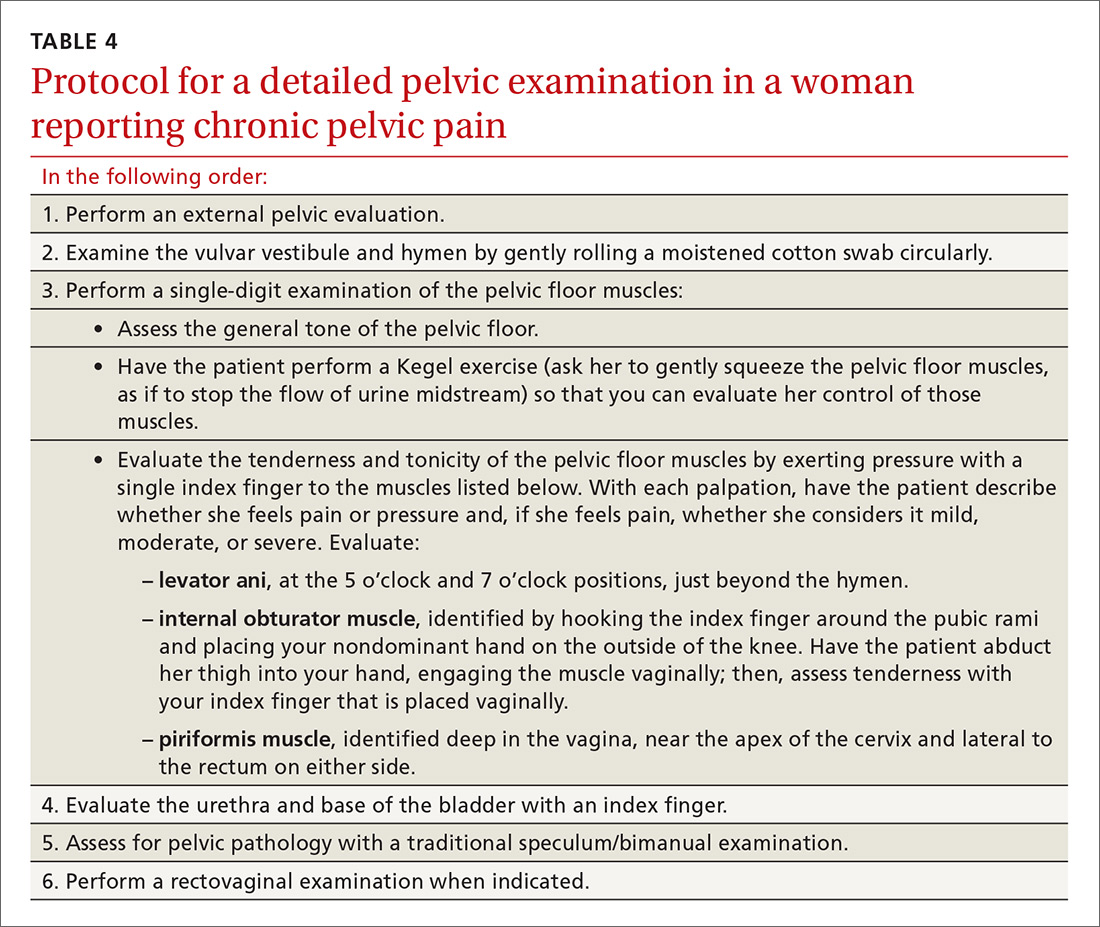

Because of the high prevalence of pelvic floor dysfunction in women with CPP, evaluation of the pelvic floor muscles is warranted.27 (A protocol for this evaluation is detailed in TABLE 4.) Pelvic dynamometry may indicate muscle spasm or chronic tension; palpation of the pelvic floor during the exam can also identify a pain generator.

Although it might be difficult to distinguish pelvic floor myofascial pain as the primary or secondary cause of pain, pelvic floor physical therapy may clarify the role of the pelvic floor response (depending on the patient’s clinical exam and history). A low-quality retrospective case study on pelvic floor physical therapy reported significant improvement in pain that was proportional to the number of sessions completed.11 Trigger-point injections and injections of botulinum toxin A have been used with reported improvement in the pelvic floor pain profile, and there is evidence to support the benefit of such injections in pelvic muscle dysfunction.12

Psychotherapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is well established as an option to manage a patient’s response to pain, including teaching coping skills for a chronic pain disorder and pain flares. Evidence supports using CBT or mindfulness techniques over usual care in reducing the intensity of pain in chronic low back pain,28 and may be helpful in CPP. Patients with CPP who received 10 treatments of Mensendieck somatocognitive therapy (a mind–body therapy technique popular in Europe) over 90 days, compared with standard treatment alone, demonstrated improvement in pain, motor function, and psychological distress that persisted 9 months after treatment.13

Lifestyle changes, complementary and alternative therapies

Although medical and nonpharmacotherapeutic treatments are often important in the

Diet modifications may relieve pain in some women with CPP. Although a systematic review in 2011 highlighted the lack of data available for the efficacy of dietary therapies for treating CPP, the authors did present data that a diet rich in antioxidants might alleviate pain sysmptoms.29 Also, a gluten-free diet might reduce the symptoms of pain related to endometriosis and, thus, improve physical functioning, among other health domains.30

Exercise can be an important factor in the management of CPP, as with other chronic pain syndromes. In functional pain syndromes, the addition or maintenance of an exercise program has been shown to decrease the amount of pain medications required, improve depressive symptoms, increase energy, and decrease stress. Exercise also improves sleep quality and one’s ability to cope with pain.31

Yoga provides a good balance of aerobic and muscle-building activity and, in the authors’ experience, is tolerated by most women with CPP.

Acupuncture has limited evidence in the treatment of pelvic pain in women. Of the available studies, most are limited to pain related to endometriosis.32

Sleep hygiene may be an important consideration in managing CPP. Sleep disturbances are reported in more than 80% of women with CPP,33 including excessive time in bed and frequent napping, resulting in daytime fatigue and feeling generally unrested. A recent meta-analysis reported mild-to-moderate immediate improvement in patients’ pain after nonpharmacotherapeutic sleep interventions.34 The National Sleep Foundation has produced a patient guide to assist in sleep hygiene.35

Devising a management strategy despite sparse evidence

Because the cause of noncyclic CPP may be multifactorial, and because the literature on the etiology of CPP is limited (and, when there is research, it is inconclusive or of poor quality36), there are few evidence-based recommendations for treating CPP. Given the paucity of quality evidence, physicians should treat patients empirically, based on their experience and their familiarity with the range of medical and nonpharmacotherapeutic options used to manage other chronic pain syndromes.

CASE 1

Ms. G’s cyclic pelvic pain was present only during menses. The dyschezia, severe pain that began only after she discontinued a combined OC, aching pain, and severe menstrual cramps are, taken together, suggestive of endometriosis, despite a normal physical exam.

Medical and surgical options were reviewed with Ms. G. She elected to undergo diagnostic laparoscopy. Several extrauterine foci of endometrial tissue were noted and excised; an LNG-IUD was inserted. Her pain improved significantly after surgery.

CASE 2

Ms. M was found to have significant pain on single-digit examination of the pelvic floor muscles, indicating likely pelvic floor muscle dysfunction. Pelvic dynamometry revealed significant tightness and spasm in the pelvic floor muscles—specifically, the levator ani complex.

Ms. M was started on gabapentin to reduce baseline pain and was referred for pelvic floor physical therapy. She felt reassured that her risk of cancer was low, considering her negative work-up, and that cancer was not the cause of her pain. Her symptoms improved greatly with a regimen of medical and physical therapy, although she continues to experience pain flares.

CORRESPONDENCE

Wendy S. Biggs, MD, Central Michigan University College of Medicine, 1632 Stone St., Saginaw, MI 48602; biggs2ws@cmich.edu.