The State of Skin of Color Centers in the United States: A Cross-Sectional Survey Study

Skin of color centers (SoCCs) in the United States have helped increase the racial/ethnic diversity of and cultivate cultural competence in practicing dermatologists as well as increase skin of color (SoC) research and education to improve patient care. The objective of this cross-sectional survey study was to provide an in-depth analysis of SoCCs and SoC specialty clinics (SoCSCs) in the United States, including their patient care focus, research, and program diversity. As the US population diversifies, it is important to highlight the programmatic, research, and educational work of existing SoCCs so that they can continue to be supported and so efforts are made to encourage the establishment of future centers at academic medical institutions across the United States.

Practice Points

- Skin of color centers in the United States work to reverse the paucity of research, education, and training in skin of color dermatology and promote the diversification of residents and faculty.

- Skin of color centers expand access to culturally competent and inclusive care for diverse patient populations.

Comment

As the number of SoCCs/SoCSCs in the United States continues to grow, it is important to highlight their programmatic, research, and educational accomplishments to show the benefits of such programs, including their ability to increase access to culturally competent and inclusive care for diverse patient populations. One study found that nearly 92% of patients in the United States seen by dermatologists are White.15 Although studies have shown that Hispanic/Latino and Black patients are less likely to seek care from a dermatologist,16,17 there is no indication that these patients have a lesser need for such specialty care. Additionally, outcomes of common dermatologic conditions often are poorer in SoC populations.15 The dermatologists leading SoCCs/SoCSCs are actively working to reverse these trends, with Black and Hispanic/Latino patients representing the majority of their patients.

Faculty and Resident Demographics and Areas of Focus—Although there are increased diversity efforts in dermatology and the medical profession more broadly, there still is much work to be done. While individuals with SoC now comprise more than 35% of the US population, only 12% of dermatology residents and 6% of academic dermatology faculty identify as either Black or Hispanic/Latino.5,8,10 These numbers are even more discouraging when considering other URiM racial groups such as Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiians or Native American/American Indians who represent 0% and 0.1% of dermatology faculty, respectively.8,10 Academic programs with SoCCs/SoCSCs are working to create a space in which these discrepancies in representation can begin to be addressed. Compared to the national 6.8% rate of URiM faculty at academic institutions, those with SoCCs/SoCSCs report closer to 10% of faculty identifying as URiM.18 Moreover, almost all programs had faculty specialized in at least 1 condition that predominantly affects patients with SoC. This is of critical importance, as the conditions that most commonly affect SoC populations—such as CCCA, hidradenitis suppurativa, and cutaneous lupus—often are understudied, underfunded, underdiagnosed, and undertreated.19-22

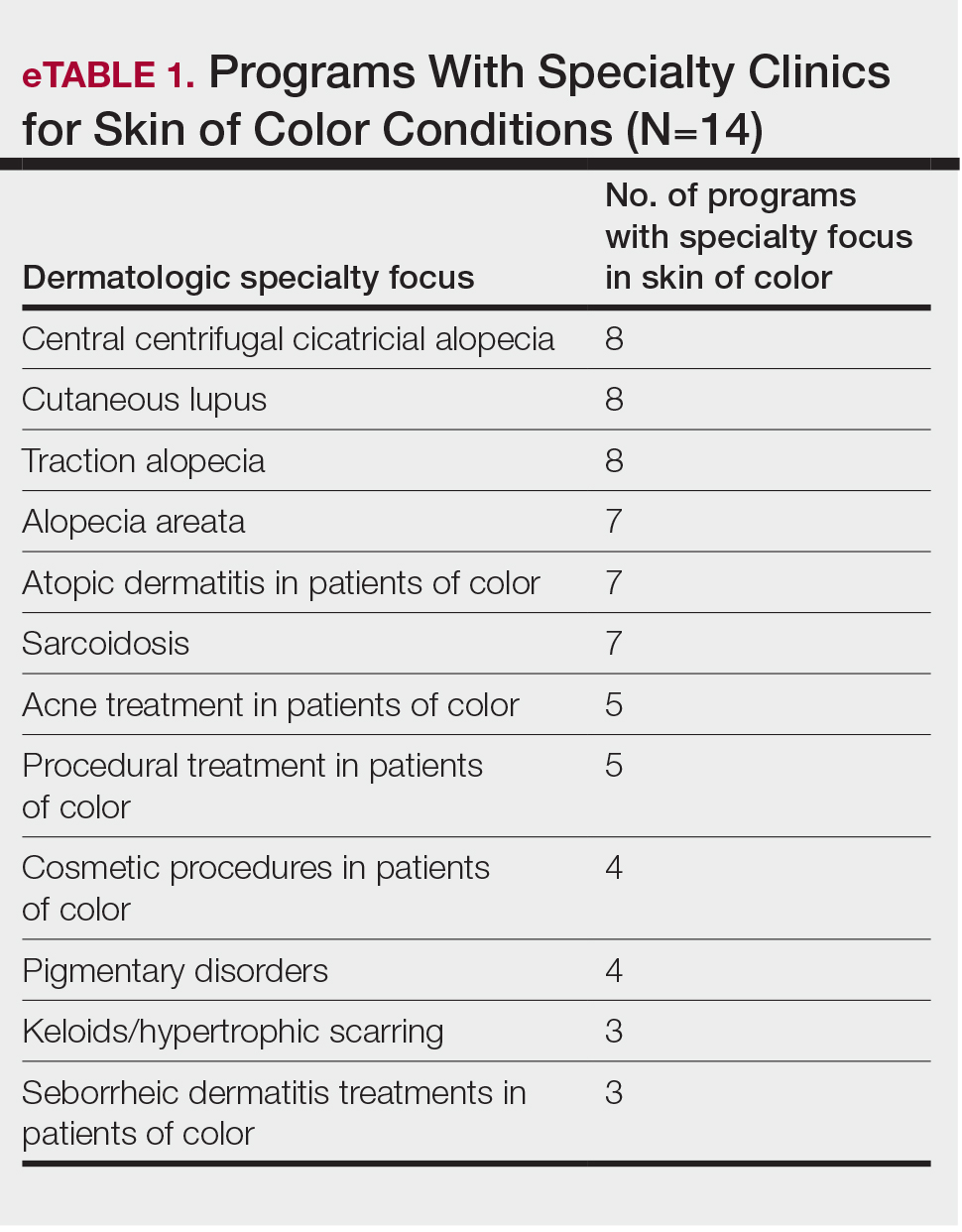

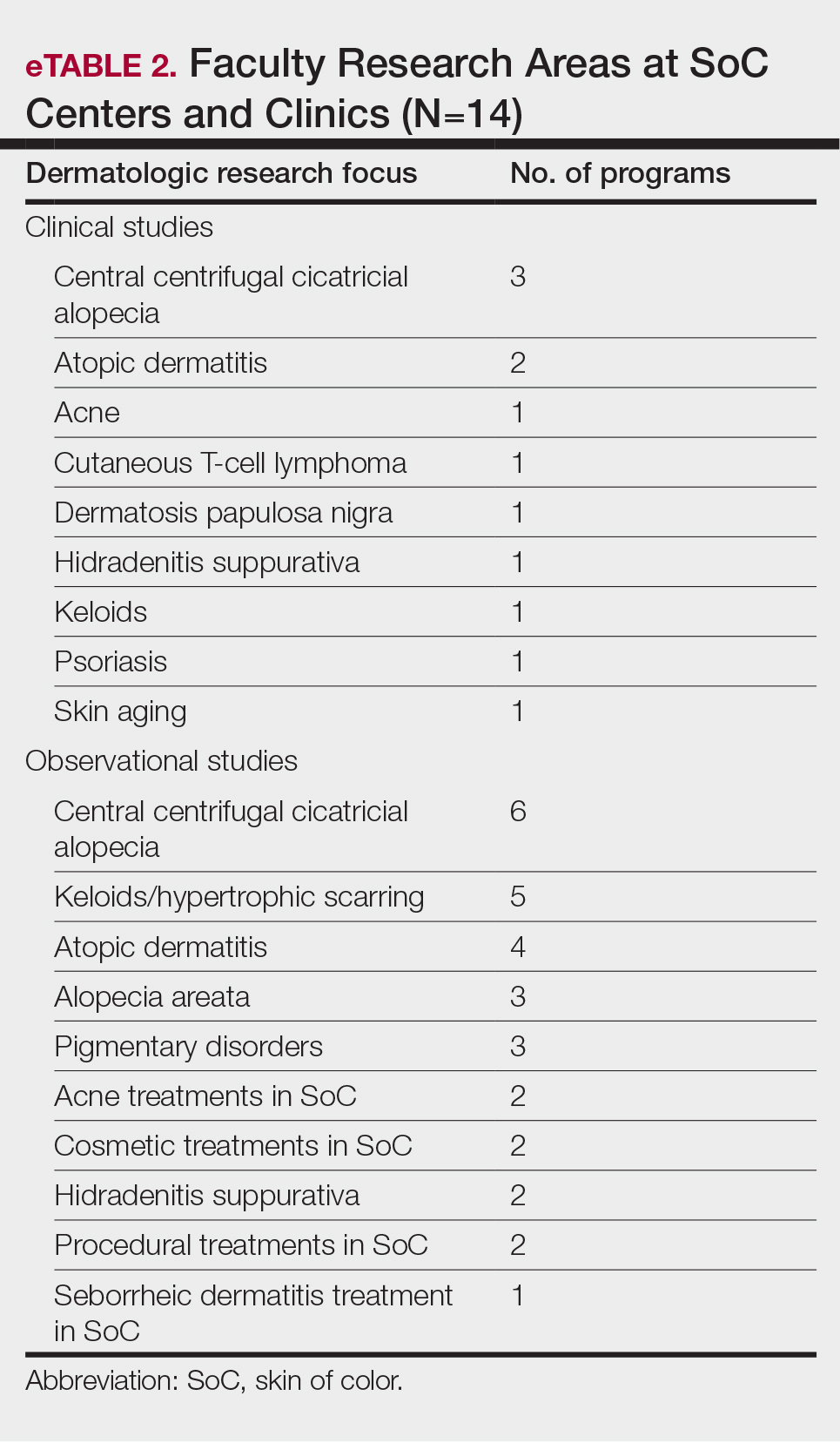

Faculty SoC Research—An important step in narrowing the knowledge gap and improving health care disparities in patients with SoC is to increase SoC research and/or to increase the representation of patients with SoC in research studies. In a 2021 study, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms race/ethnicity, dyschromia, atopic dermatitis, and acne was conducted to investigate publications pertaining to the top 3 most common chief concerns in patients with SoC. Only 1.6% of studies analyzed (N=74,941) had a specific focus on SoC.12 A similar study found that among the top 5 dermatology-focused research journals, only 3.4% of all research (N=11,003) on the top 3 most common chief concerns in patients with SOC was conducted in patients with SoC.23 Research efforts focused on dermatologic issues that affect patients with SoC are a priority at SoCCs/SoCSCs. In our study, all respondents indicated that they had at least 1 ongoing observational study; the most commonly studied conditions were CCCA, keloids/hypertrophic scarring, and atopic dermatitis, all of which are conditions that either occur in high frequency or primarily occur in SoC. Only 35.71% (5/14) of respondents had active clinical trials related to SoC, and only 21.43% (3/14) and 28.57% (4/14) had internal and external funding, respectively. Although research efforts are a priority at SoCCs/SoCSCs, our survey study highlights the continued paucity of formal clinical trials as well as funding for SoC-focused research. Improved research efforts for SoC must address these deficits in funding, academic support, and other resources.

It also is of great importance for institutions to provide support for trainees wanting to pursue SoC research. Encouragingly, more than half (57.14%) of SoCCs/SoCSCs have developed formal research opportunities for residents, and nearly 64.29% have formal opportunities for medical students. These efforts to provide early experiences in SoC research are especially impactful by cultivating interest in working with populations with SoC and hopefully inspiring future dermatologists to engage in further SoC research.

SoC Education and Diversity Initiatives—Although it is important to increase representation of URiM physicians in dermatology and to train more SoC specialists, it is imperative that all dermatologists feel comfortable recognizing and treating dermatologic conditions in patients of all skin tones and all racial/ethnic backgrounds; however, many studies suggest that residents not only lack formal didactics and education in SoC, but even more unsettling, they also lack confidence in treating SoC.13,24 However, one study showed that this can be changed; Mhlaba et al25 assessed a SoC curriculum for dermatology residents, and indeed all of the residents indicated that the curriculum improved their ability to treat SoC patients. This deficit in dermatology residency training is specifically addressed by SoCCs/SoCSCs. In our study, all respondents indicated that residents rotate through their centers. Moreover, our study found that most of the academic institutions with SoCCs/SoCSCs provide a SoC didactic curriculum for residents, and almost all of the programs invited SoC specialists to give guest lectures. This is in contrast to a 2022 study showing that 63.2% (N=125) of graduating dermatology residents reported receiving SoC-specific didactics, sessions, or lectures.14 These findings highlight the critical role that SoCCs/SoCSCs can provide in dermatology residency training.

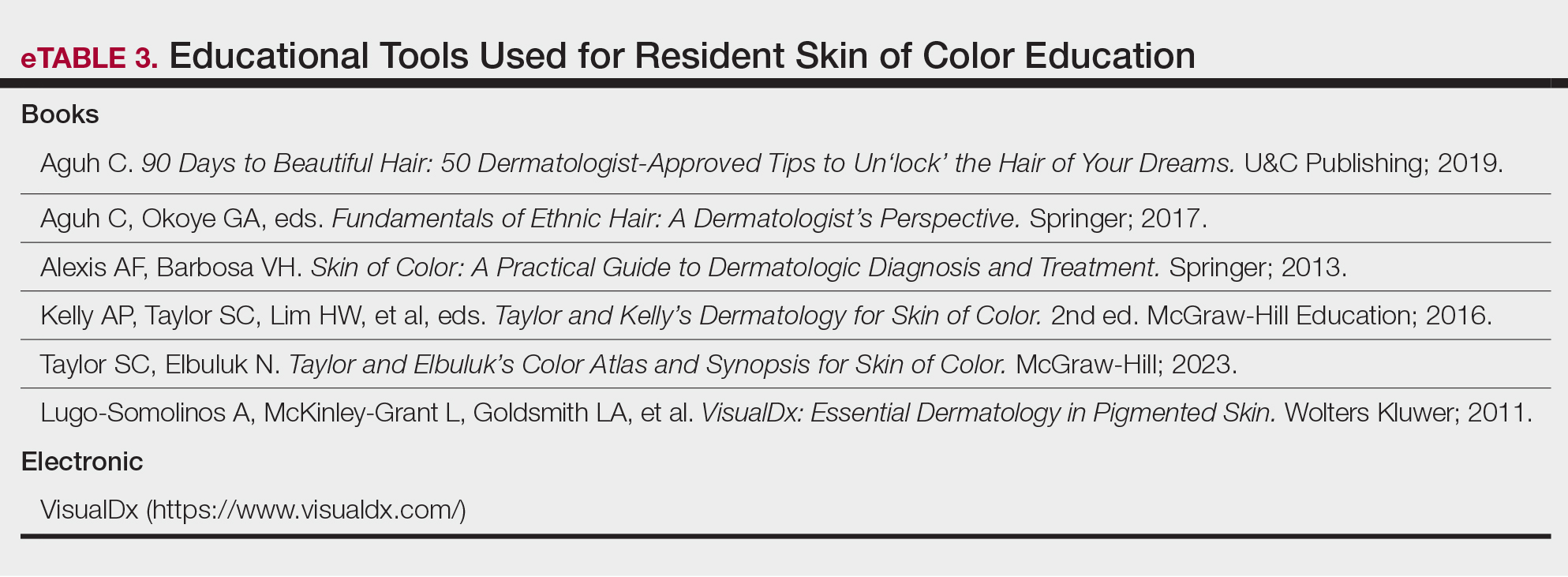

Although SoCCs/SoCSCs have made considerable progress, there is still much room for improvement. Namely, only half of the respondents in our study indicated that their program has formally incorporated a SoC textbook into resident education (eTable 3). Representation of SoC in the textbooks that dermatology residents use is critically important because these images form the foundation of the morphologic aids of diagnosis. Numerous studies have analyzed popular dermatologic textbooks used by residency programs nationwide, finding the number of SoC images across dermatology textbooks ranging from 4% to 18%.26,27 The use of standard dermatology textbooks is not enough to train residents to be competent in diagnosing and treating patients with SoC. There should be a concerted effort across the field of dermatology to encourage the development of a SoC educational curriculum at every academic dermatology program, including SoC textbooks, Kodachromes, and online/electronic resources.

Efforts to increase diversity in dermatology and dermatologic training should start in medical school preclinical curriculums and medical student rotations. Although our survey did not assess current medical student curricula, the benefits of academic institutions with SoCCs/SoCSCs are highlighted by the ability for both home and visiting medical students to rotate through the centers and gain early exposure to SoC dermatology. Most of the programs even provide scholarships and/or grants for URiM students to help fund their rotations, which is of critical importance considering the mounting data that the financial burden of visiting rotations disproportionately affects URiM students.28

Study Limitations—Although we did an extensive search and believe to have correctly identified all 15 formal SoCCs/SoCSCs with a high response rate (93.3%), there are institutions that do not have formalized SoCCs/SoCSCs but are known to serve SoC populations. Likewise, there are private dermatology practices not associated with academic centers that have SoC specialists and positively contribute to SoC patient care, research, and education that were not included in this study. Additionally, the data for this study were collected in 2020 and analyzed in 2021, so it is possible that not all SoCCs, divisions, or clinics were included in this study, particularly if established after 2021.

Conclusion

As the United States continues to diversify, the proportion of patients with SoC will continue to grow, and it is imperative that this racial, ethnic, and cultural diversity is reflected in the dermatology workforce as well as research and training. The current deficits in medical training related to SoC populations and the importance for patients with SoC to find dermatologists who can appropriately treat them is well known.29 Skin of color centers/SoCSCs strive to increase access to care for patients with SoC, improve cultural competency, promote diversity among faculty and trainees, and encourage SoC research and education at all levels. We urge academic dermatology training programs to make SoC education, research, and patient care a departmental priority. Important first steps include departmental diversification at all levels, incorporating SoC into curricula for residents, providing and securing funding for SoC research, and supporting the establishment of more formal SoCCs and/or SoCSCs to help reduce dermatologic health care disparities among patients with SoC and improve health equity.

Appendix