The State of Skin of Color Centers in the United States: A Cross-Sectional Survey Study

Skin of color centers (SoCCs) in the United States have helped increase the racial/ethnic diversity of and cultivate cultural competence in practicing dermatologists as well as increase skin of color (SoC) research and education to improve patient care. The objective of this cross-sectional survey study was to provide an in-depth analysis of SoCCs and SoC specialty clinics (SoCSCs) in the United States, including their patient care focus, research, and program diversity. As the US population diversifies, it is important to highlight the programmatic, research, and educational work of existing SoCCs so that they can continue to be supported and so efforts are made to encourage the establishment of future centers at academic medical institutions across the United States.

Practice Points

- Skin of color centers in the United States work to reverse the paucity of research, education, and training in skin of color dermatology and promote the diversification of residents and faculty.

- Skin of color centers expand access to culturally competent and inclusive care for diverse patient populations.

Methods

We conducted an investigator-initiated, multicenter, cross-sectional survey study of all SoCCs in the United States and their respective academic residency programs. Fifteen formal SoCCs and/or SoCSCs were identified by dermatology program websites and an article by Tull et al2 on the state of ethnic skin centers. All programs and centers identified were associated with a dermatology residency program accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

A 42-item questionnaire was sent via email to the directors of these centers and clinics with the intent to collect descriptive information about each of the SoCCs, the diversity of the faculty and residents of the associated dermatology department, current research and funding, diversity and inclusion initiatives, and trainee education from March through April 2020. Data were analyzed using Excel and SPSS statistical software to obtain descriptive statistics including the mean value numeric trends across programs.

This study underwent expedited review and was approved by the University of Southern California (Los Angeles, California) institutional review board (IRB #HS-20-00113). Patient consent was not applicable, as no information was collected about patients.

Results

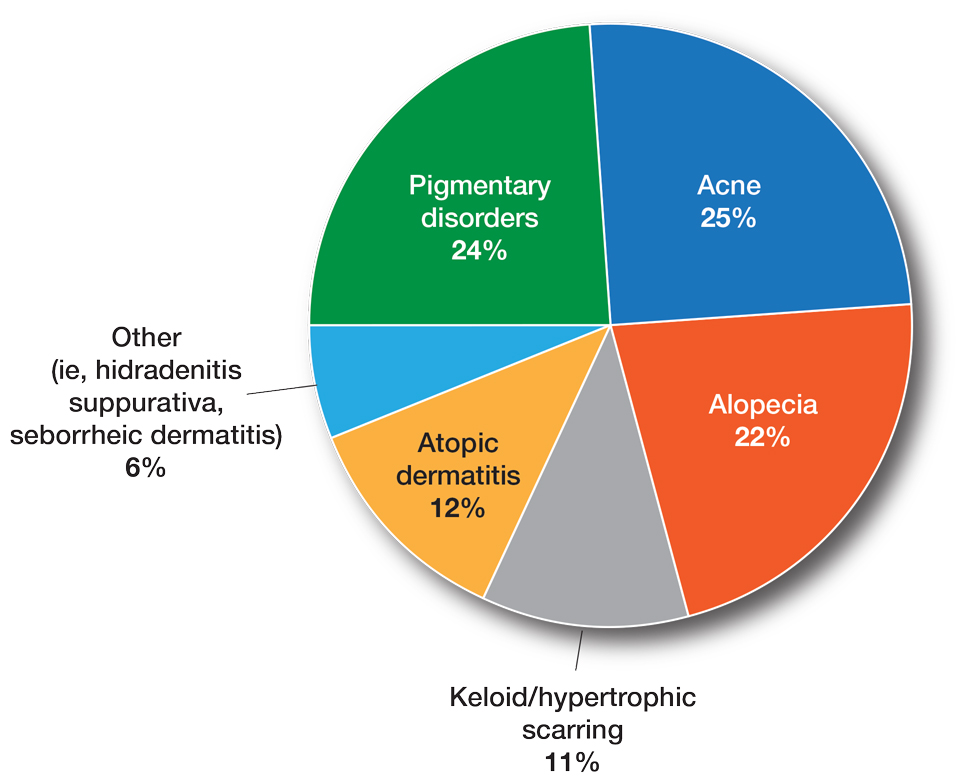

Fourteen directors from SoCCs/SoCSCs completed the questionnaire (93.3% response rate). Most centers were located in urban areas (12/14 [85.71%]), except for 2 in rural or suburban settings (Table). Most of the SoCCs/SoCSCs were located in the South (5/14 [35.71%]), followed by the Northeast (4/14 [28.57%]), West (3/14 [21.43%]), and Midwest (2/14 [14.29%])(Table). Six (42.86%) of the programs had a SoCSC, 3 (21.43%) had a formal SoCC, and 5 (35.71%) had both. Across all centers, the most common population seen and treated was Black/African American followed by Hispanic/Latino and Asian, respectively. The most commonly seen dermatologic conditions were acne, pigmentary disorders, alopecia, and atopic dermatitis (Figure). The most common cosmetic practice performed for patients with SoC was dermatosis papulosa nigra/seborrheic keratosis removal, followed by laser treatments, skin tag removal, chemical peels, and neuromodulator injections, respectively.

Faculty and Resident Demographics and Areas of Focus—The demographics and diversity of the dermatology faculty and residents at each individual institution also were assessed. The average number of full-time faculty at each institution was 19.4 (range, 2–48), while the average number of full-time faculty who identified as underrepresented in medicine (URiM) was 2.1 (range, 0–5). The average number of residents at each institution was 17.1 (range, 10–31), while the average number of URiM residents was 1.7 (range, 1–3).

The average number of full-time faculty members at each SoCC was 1.6 (range, 1–4). The majority of program directors reported having other specialists in their department that also treated dermatologic conditions predominantly affecting patients with SoC (10/14 [71.43%]). The 3 most common areas of expertise were alopecia, including central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA); cutaneous lupus; and traction alopecia (eTable 1).

Faculty SoC Research—Only a minority of programs had active clinical trials related to SoC (5/14 [35.71%]). Clinical research was the most common type of research being conducted (11/14 [78.57%]), followed by basic science/translational (4/14 [28.57%]) and epidemiologic research (2/14 [14.29%]). The most commonly investigated conditions for observational studies included CCCA, keloids/hypertrophic scarring, and atopic dermatitis (eTable 2). Only 8 of 14 programs had formal SoC research opportunities for residents (57.14%), while 9 had opportunities for medical students (64.29%).

Few institutions had internal funding (3/14 [21.43%]) or external funding (4/14 [28.57%]) for SoC research. Extramural fun ding sources included the Skin of Color Society, the Dermatology Foundation, and the Radiation Oncology Institute, as well as industry funding. No federal funding was received by any of the sites.

Skin of Color Education and Diversity Initiatives—All 14 programs had residents rotating through their SoCC and/or SoCSCs. The vast majority (12/14 [85.71%]) indicated resident exposure to clinical training at the SoCC and/or SoCSC during all 3 years of training. Residents at most of the programs spent 1 to 3 months rotating at the SoCC/SoCSC (6/14 [42.86%]). The other programs indicated residents spent 3 to 6 months (3/14 [21.43%]) or longer than 6 months (3/14 [21.4%]), and only 2 programs (14.29%) indicated that residents spent less than 1 month in the SoCC/SoCSC.

The majority of programs offered a SoC didactic curriculum for residents (10/14 [71.43%]), with an average of 3.3 SoC-related lectures per year (range, 0–5). Almost all programs (13/14 [92.86%]) invited SoC specialists from outside institutions as guest lecturers. Half of the programs (7/14 [50.0%]) used a SoC textbook for resident education. Only 3 programs (21.43%) offered at least 1 introductory SoC dermatology lecture as part of the preclinical medical student dermatology curriculum.

Home institution medical students were able to rotate at their respective SoCC/SoCSC at 11 of 14 institutions (78.57%), while visiting students were able to rotate at half of the programs (7/14 [50.0%]). At some programs, rotating at the SoCC/SoCSC was optional and was not formally integrated into the medical student rotation schedule for both home and visiting students (1/14 [7.14%] and 4/14 [28.57%], respectively). A majority of the programs (8/14 [57.14%]) offered scholarships and/or grants for home and/or visiting URiM students to help fund away rotations.

Despite their SoC focus, only half of the programs with SoCCs/SoCSCs had a formal committee focused on diversity and inclusion (7/14 [50.0%]) Additionally, only 5 of 14 (35.71%) programs had any URiM outreach programs with the medical school and/or the local community.