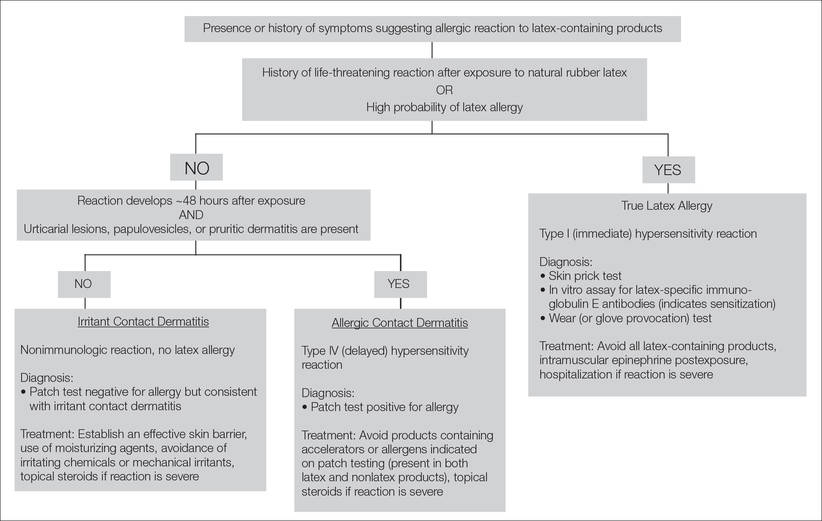

Differentiation of Latex Allergy From Irritant Contact Dermatitis

The term latex allergy refers to a hypersensitivity to products containing natural rubber latex. Individuals with true latex allergy have developed type I (immediate) hypersensitivity due to previous sensitization and production of immunoglobulin E antibodies. Other forms of adverse reactions to latex-containing products may develop, including irritant contact dermatitis and type IV (delayed) hypersensitivity reactions, although they do not indicate true latex allergy. Several diagnostic tests are available to differentiate true latex allergy from irritant contact dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis. It is crucial to determine the type of hypersensitivity in patients labeled with “latex allergy” in order to establish the most effective treatment regimen.

Practice Points

- The term latex allergy often is used as a general diagnosis to describe 3 types of reactions to natural rubber latex, including irritant contact dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis (type IV hypersensitivity reaction), and true latex allergy (type I hypersensitivity reaction).

- The latex skin prick test is considered the gold standard for diagnosis of true latex allergy, but this method is not available in the United States. In vitro assay for latex-specific immunoglobulin E antibodies is the best alternative.

The most noninvasive method of latex allergy testing is an in vitro assay for latex-specific IgE antibodies, which can be detected by either a radioallergosorbent test (RAST) or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The presence of antilatex IgE antibodies confirms sensitization but does not necessarily mean the patient will develop a symptomatic reaction following exposure. Due to the unavailability of a standardized reagent for the skin prick test in the United States, evaluation of latex-specific serum IgE levels may be the best alternative. While the skin prick test has the highest sensitivity, the sensitivity and specificity of latex-specific serum IgE testing are 50% to 90% and 80% to 87%, respectively.6

The wear test (also known as the use or glove provocation test), can be used to diagnose clinically symptomatic latex allergy when there is a discrepancy between the patient’s clinical history and results from skin prick or serum IgE antibody testing. To perform the wear test, place a natural rubber latex glove on one of the patient’s fingers for 15 minutes and monitor the area for development of urticaria. If there is no evidence of allergic reaction within 15 minutes, place the glove on the whole hand for an additional 15 minutes. The patient is said to be nonreactive if a latex glove can be placed on the entire hand for 15 minutes without evidence of reaction.3

Lastly, patch testing can differentiate between irritant contact and allergic contact (type IV hypersensitivity) dermatitis. Apply a small amount of each substance of interest onto a separate disc and place the discs in direct contact with the skin using hypoallergenic tape. With type IV latex hypersensitivity, the skin underneath the disc will become erythematous with developing papulovesicles, starting between 2 and 5 days after exposure. The Figure outlines the differentiation of true latex allergy from irritant and allergic contact dermatitis and identifies methods for making these diagnoses.

General Medical Protocol With Latex Reactions

To reduce the incidence of latex allergic reactions among health care workers and patients, Kumar2 recommends putting a protocol in place to document steps in preventing, diagnosing, and treating latex allergy. This protocol includes employee and patient education about the risks for developing latex allergy and the signs and symptoms of a reaction; available diagnostic testing; and alternative products (eg, hypoallergenic gloves) that are available to individuals with a known or suspected allergy. At-risk health care workers who have not been sensitized should be advised to avoid latex-containing products.3 Routine questioning and diagnostic testing may be necessary as part of every preoperative assessment, as there have been reported cases of anaphylaxis in patients with undocumented allergies.7 Anaphylaxis caused by latex allergy is the second leading cause of perioperative anaphylaxis, accounting for as many as 20% of cases.8 With the use of preventative measures and early identification of at-risk patients, the incidence of latex-related anaphylaxis is decreasing.8 Ascertaining valuable information about the patient’s medical history, such as known allergies to foods that have cross-reactivity to latex (eg, bananas, mango, kiwi, avocado), is one simple way of identifying a patient who should be tested for possible underlying latex allergy.8 Total avoidance of latex-containing products (eg, in the workplace) can further reduce the incidence of allergic reactions by decreasing primary sensitization and risk of exposure.

Conclusion

Patients claiming to be allergic to latex without documentation should be tested. The diagnostic testing available in the United States includes patch testing, wear (or glove provocation) testing, or assessment of IgE antibody titer. Accurate differentiation among irritant contact dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis, and true latex allergy is paramount for properly educating patients and effectively treating these conditions. Additionally, distinguishing patients with true latex allergy from those who have been misdiagnosed can save resources and reduce health care costs.