Interpreting liver function tests

Patients’ elevated LFT results can indicate hepatocyte injury, cholestasis, or both.

If repeat results are abnormal, obtain the patient’s consent to inform the primary care provider. Then take a thorough history and perform a focused physical exam. In the history, focus on use of prescription and nonprescription medications, including over-the-counter and herbal therapies, alcohol, and drugs of abuse, such as MDMA (“ecstasy”), phencyclidine (“angel dust”), and glues or solvents. Also assess for risk factors for infectious hepatitis, such as IV drug use, work-related blood exposure, and tattoos. Ask about a family history of liver disease. Focus your physical exam on visible stigmata of chronic liver disease, such as jaundice, temporal wasting, ascites, and palmar erythema.

Next, analyze the severity and pattern of the LFT abnormality. Liver injury is defined as:

- ALT >3 times the upper limit of normal

- ALP >2 times the upper limit of normal

- or total bilirubin >2 times the upper limit of normal if associated with any elevation of ALT or ALP.5

If ALT elevations predominate, consider hepatocellular injury. If ALP elevations predominate, suspect cholestatic injury. Elevations of both ALT and ALP suggest a mixed pattern of hepatocellular and cholestatic injury.

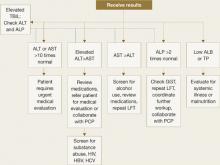

Figure 1 Interpreting liver function test results

ALB: albumin; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; GGT: gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase; HBV: hepatitis B virus; HCV: hepatitis C virus; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; LFT: liver function test; PCP: primary care provider; TBIL: total bilirubin; TP: total protein

CASE CONTINUED: Pinpointing a diagnosis

Mrs. W undergoes repeat LFTs with GGT testing, screening tests for hepatitis B and C, and a comprehensive physical exam. The psychiatrist screens for alcohol use, asks the patient about her use of herbal therapies and substance abuse relapse, and evaluates cognitive mental status for symptoms of encephalopathy. Results reveal that Mrs. W’s ALT and AST are elevated because of chronic active hepatitis C.

Causes of hepatocellular injury

Further evaluation of your patient’s test results can help narrow down potential causes of liver damage. If your patient’s ALT is disproportionately elevated, estimate the:

- severity of aminotransferase elevation

- ratio of AST:ALT

- rate of change over multiple LFTs.

If AST or ALT is >10 times normal, consider toxin-induced or ischemic injury.6 An AST:ALT ratio of 2:1 or 3:1, especially when associated with elevated GGT, strongly suggests alcohol-induced injury. With acute mild transaminase elevations—ALT>AST, 2 to 3 times normal—suspect medication-related injury.

A variety of factors and conditions can result in hepatocellular damage:

Common causes

Medications. Many drugs, including common psychotropics, can cause elevated liver enzymes (Table 2).5 As little as 4 grams per day of acetaminophen can cause mild transaminitis.4 Antidepressants, second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), and anticonvulsants can cause increases in AST and ALT.7 If liver enzymes rise after a patient starts a new medication, drug-related liver toxicity is likely. Remember to consider a patient’s use of drugs of abuse and herbal therapies.

Discontinuing the suspect agent usually produces steady (although sometimes slow) improvement in LFTs. Use serial LFT testing and focused history and physical examinations to confirm improvement.

Alcohol. Screen for alcohol abuse using the CAGE questionnaire, the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, or a similar tool. More than 90% of patients with an AST:ALT ratio of 2:1 have alcoholic liver disease; this percentage increases to >96% when the ratio is 3:1.1 A 2-fold increase in GGT in a patient with an AST:ALT ratio >2:1 further supports the diagnosis. In patients with alcohol abuse, AST rarely exceeds 10 times normal.5

Hepatitis C. The prevalence of hepatitis C is increasing among patients with severe mental illness, especially a dual diagnosis.8 Hepatitis C rarely causes acute symptoms.

Offer a hepatitis C antibody screening to test patients with even a remote history of IV drug use or comorbid substance abuse. Patients with a positive hepatitis C antibody test or a negative hepatitis C antibody test but a high risk for the disease should receive further testing.9

Hepatitis B. Risk factors include exposure to blood, sexual transmission, and emigration from endemic areas in Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Initial screening panels include tests for hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B surface antibody, and hepatitis B core antibody. Positive B surface antigen and core antibody tests indicate infection.

NASH. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is the most common cause of mild transaminitis in the Western world (Box).4,10,11

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is inflammatory liver disease of uncertain pathogenesis that commonly occurs with metabolic syndrome. It affects up to 5% of Americans, most often those who are middle-aged and overweight or obese, hyperlipidemic, or diabetic. NASH resembles alcoholic liver disease but occurs in people who drink little or no alcohol. In addition to inflammation, it is characterized by accumulation of fat and fibrous tissue in the liver. Typically patients are asymptomatic, but NASH can lead to cirrhosis.

NASH is a common cause of mild transaminitis. Aminotransferase levels are usually <4 times the normal value.10 Thirteen percent of patients with NASH have normal LFT results despite histologic abnormalities.4 NASH is a diagnosis of exclusion that is confirmed by liver biopsy.

NASH has no specific therapies or cure. Treatment focuses on controlling associated conditions such as diabetes, obesity, and hyperlipidemia. In obese patients, weight loss is the cornerstone of treatment. If you prescribe a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA) for a patient who has NASH, be aware that SGAs increase the risk of hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia, which can exacerbate NASH.11