Schizoaffective disorder: A challenging diagnosis

Paying close attention to the temporal relationship of psychotic and mood symptoms is key.

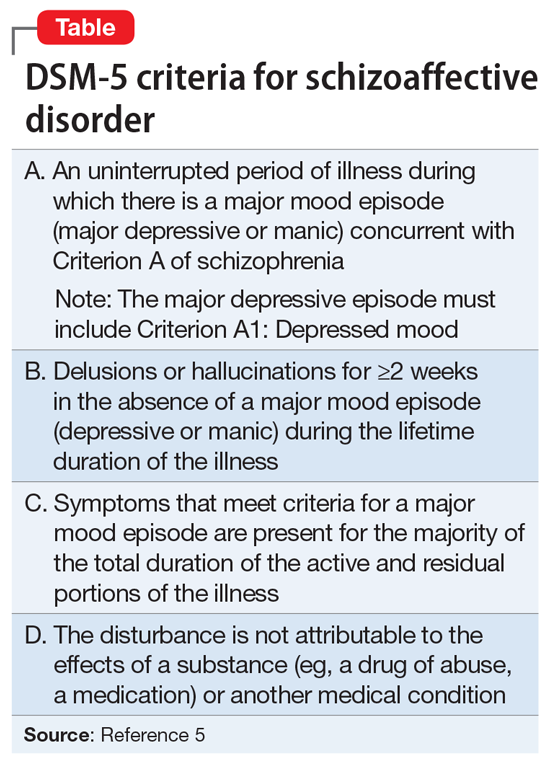

DSM-5 provides a clearer separation between schizophrenia with mood symptoms, bipolar disorder, and SAD (Table5). In addition, DSM-5 shifts away from the DSM-IV diagnosis of SAD as an episode, and instead focuses more on the longitudinal course of the illness. It has been suggested that this change will likely lead to reduced rates of diagnosis of SAD.6 Despite improvements in classification, the diagnosis remains controversial (Box7-11).

Box 1

Despite improvements in classification, controversy continues to swirl around the question of whether schizoaffective disorder (SAD) represents an independent disorder that stands apart from schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, whether it is a form of schizophrenia, or whether it is a form of bipolar disorder or a depressive disorder.7,8 Other possibilities are that SAD is heterogeneous or that it represents a middle point on a spectrum that bridges mood and psychotic disorders. While the merits of each possibility are beyond the scope of this review, it is safe to say that each possibility has its proponents. For these reasons, some argue that the concept itself lacks validity and shows the pitfalls of our classification system.7

Poor diagnostic reliability is one reason for concerns about validity. Most recently, a field trial using DSM-5 criteria produced a kappa of 0.50, which is moderate,9 but earlier definitions produced relatively poor results. Wilson et al10 point out that Criterion C, which concerns duration of mood symptoms, produces a particularly low kappa. Another reason is diagnostic switching, whereby patients initially diagnosed with 1 disorder receive a different diagnosis at followup. Diagnostic switching is especially problematic for SAD. In a large meta-analysis by Santelmann et al,11 36% of patients initially diagnosed with SAD had their diagnosis changed when reassessed. This diagnostic shift tended more toward schizophrenia than bipolar disorder. In addition, more than one-half of all patients initially diagnosed with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depressive disorder were re-diagnosed with SAD when reassessed.

DSM-5 subtypes and specifiers

In DSM-5,SAD has 2 subtypes5:

- Bipolar type. The bipolar type is marked by the presence of a manic episode (major depressive episodes may also occur)

- Depressive type. The depressive type is marked by the presence of only major depressive episodes.

SAD also includes several specifiers, with the express purpose of giving clinicians greater descriptive ability. The course of SAD can be described as either “first episode,” defined as the first manifestation of the disorder, or as having “multiple episodes,” defined as a minimum of 2 episodes with 1 relapse. In addition, SAD can be described as an acute episode, in partial remission, or in full remission. The course can be described as “continuous” if it is clear that symptoms have been present for the majority of the illness with very brief subthreshold periods. The course is designated as “unspecified” when information is unavailable or lacking. The 5-point Clinician-Rated Dimensions of Psychosis Symptoms was introduced to enable clinicians to make a quantitative assessment of the psychotic symptoms, although its use is not required.

Epidemiology and gender ratio

The epidemiology of SAD has not been well studied. DSM-5 estimates that SAD is approximately one-third as common as schizophrenia, which has a lifetime prevalence of 0.5% to 0.8%.5 This is similar to an estimate by Perälä et al12 of a 0.32% lifetime prevalence based on a nationally representative sample of persons in Finland age ≥30. Scully et al13 calculated a prevalence estimate of 1.1% in a representative sample of adults in rural Ireland. Based on pooled clinical data, Keck et al14 estimated the prevalence in clinical settings at 16%, similar to the figure of 19% reported by Levinson et al15 based on data from New York State psychiatric hospitals. In clinical practice, the diagnosis of SAD is used frequently when there is diagnostic uncertainty, which potentially inflates estimates of lifetime prevalence.

The prevalence of SAD is higher in women than men, with a sex ratio of about 2:1, similar to that seen in mood disorders.13,16-19 There are an equal number of men and women with the bipolar subtype, but a female preponderance with the depressive subtype.5 The bipolar subtype is more common in younger patients, while the depressive subtype is more common in older patients. SAD is a rare diagnosis in children.20

Continue to: Course and outcome