A concise guide to monoamine oxidase inhibitors

A better understanding of the risks can lead to increased use of these highly effective agents. First of 2 parts.

VIDEO: Listen to Dr. Meyer discuss what to tell patients about diet and monoamine oxidase inhibitors.

What is tyramine? Tyramine is a biogenic amine that is virtually absent in fresh animal protein sources but is enriched after decay or fermentation.20 Modern food processing and handling methods have significantly limited the tyramine content in processed foods, with the exception of certain cheeses and sauces, as discussed below. Moreover, modern assaying techniques using high-performance liquid chromatography have generated extremely accurate assessments of the tyramine content of specific foods.21 Data published prior to 2000 are not reliable, because many of these publications employed outdated methods.17

When ingested, tyramine is metabolized by gut MAO-A, with doses up to 400 mg causing no known effects, although most people rarely ingest >25 mg during a meal.22 In addition to being a substrate for MAO-A, tyramine is also a substrate for the dopamine transporter, norepinephrine transporter (NET), the vesicular monoamine transporter 2, and TAAR1.23 Tyramine enters the cell via NET, where it interacts with TAAR1, a G protein-coupled receptor that is responsive to trace amines, such as tyramine, as well as amphetamines.20 The agonist properties at TAAR1 are the presumed site of action for the BP effects of tyramine, because binding results in potent release of norepinephrine.20,24 When tyramine is supplied to an animal in which MAO-A is inhibited, the decreased peripheral catabolism of tyramine results in markedly increased norepinephrine release by peripheral adrenergic neurons. Moreover, the absence of MAO-A activity in those neurons prevents any norepinephrine breakdown, resulting in robust synaptic norepinephrine delivery and peripheral effects.

All orally administered irreversible MAOIs potently inhibit gut and systemic MAO-A, and are susceptible to the impact of significant tyramine ingestion. The exception is selegiline transdermal (Figure 112), as appreciable gut MAO-A inhibition does not occur until doses >6 mg/24 hours are reached.22 No significant pressor response was seen in participants taking selegiline transdermal, 6 mg/24 hours for 13 days, who consumed a meal that provided 400 mg of tyramine.22 Conversely, for oral agents that produce gut MAO-A inhibition, tyramine doses as low as 8 to 10 mg (when administered as tyramine capsules) may increase systolic pressure by 30 mm Hg.25 The dietary warnings do not apply to rasagiline, which is a selective MAO-B inhibitor, although rasagiline may have an impact on resting BP; the prescribing information for rasagiline includes warnings about hypotension and hypertension.26

What to tell patients about tyramine. Although administering pure tyramine capsules can induce a measurable change in systolic BP, when ingested as food, tyramine doses <50 mg are unlikely to cause an increase in BP sufficient to warrant clinical intervention, although some individuals can be sensitive to 10 to 25 mg.19 When discussing with patients safety issues related to diet, there are a few important concepts to remember19:

- In an era when the tyramine content of foods was much higher (1960 to 1964) and MAOI users received no dietary guidance, only 14 deaths were reported among an estimated 1.5 million patients who took MAOIs.

- MAOIs do not raise BP, and their use is associated with orthostasis in some patients.

- Routine exercise or other vigorous activities (eg, weightlifting) can raise systolic pressure well above 200 mm Hg, and routine baseline systolic pressures, ranging from 180 to 220 mm Hg, do not increase the risk of subarachnoid hemorrhage.

- Hospital evaluation is needed only if a substantial amount of tyramine is ingested (eg, estimated ≥100 mg), and self-monitoring shows a systolic BP ≥220 mm Hg over a prolonged period (eg, 2 hours). Ingestion of 100 mg of tyramine would almost certainly have to be intentional, as it would require one to consume 3.5 oz of the most highly tyramine-laden cheeses.

Emphasize to patients that only a small number of highly aged cheeses, foods, and sauces contain high quantities of tyramine, and that even these foods can be enjoyed in small amounts. All patients who are prescribed an MAOI also should purchase a portable BP cuff for those rare instances when a dietary indiscretion may have occurred and the person experiences a headache within 1 to 2 hours after tyramine ingestion. Most reactions are self-limited and resolve over 2 to 4 hours.

Patients who ingest ≥100 mg of tyramine should be evaluated by a physician. Under no circumstances should a patient be given a prescription for nifedipine or other medications that can abruptly lower BP, because this may result in complications, including myocardial infarction.27,28 Counsel patients to remain calm. Some clinicians endorse the use of low doses of benzodiazepines (the equivalent of alprazolam 0.5 mg) to facilitate this, because anxiety elevates BP. A recent emergency room study of patients with an initial systolic BP ≥160 mm Hg or diastolic BP ≥100 mm Hg without end organ damage demonstrated that alprazolam, 0.5 mg, was as effective as captopril, 25 mg, in lowering BP.29

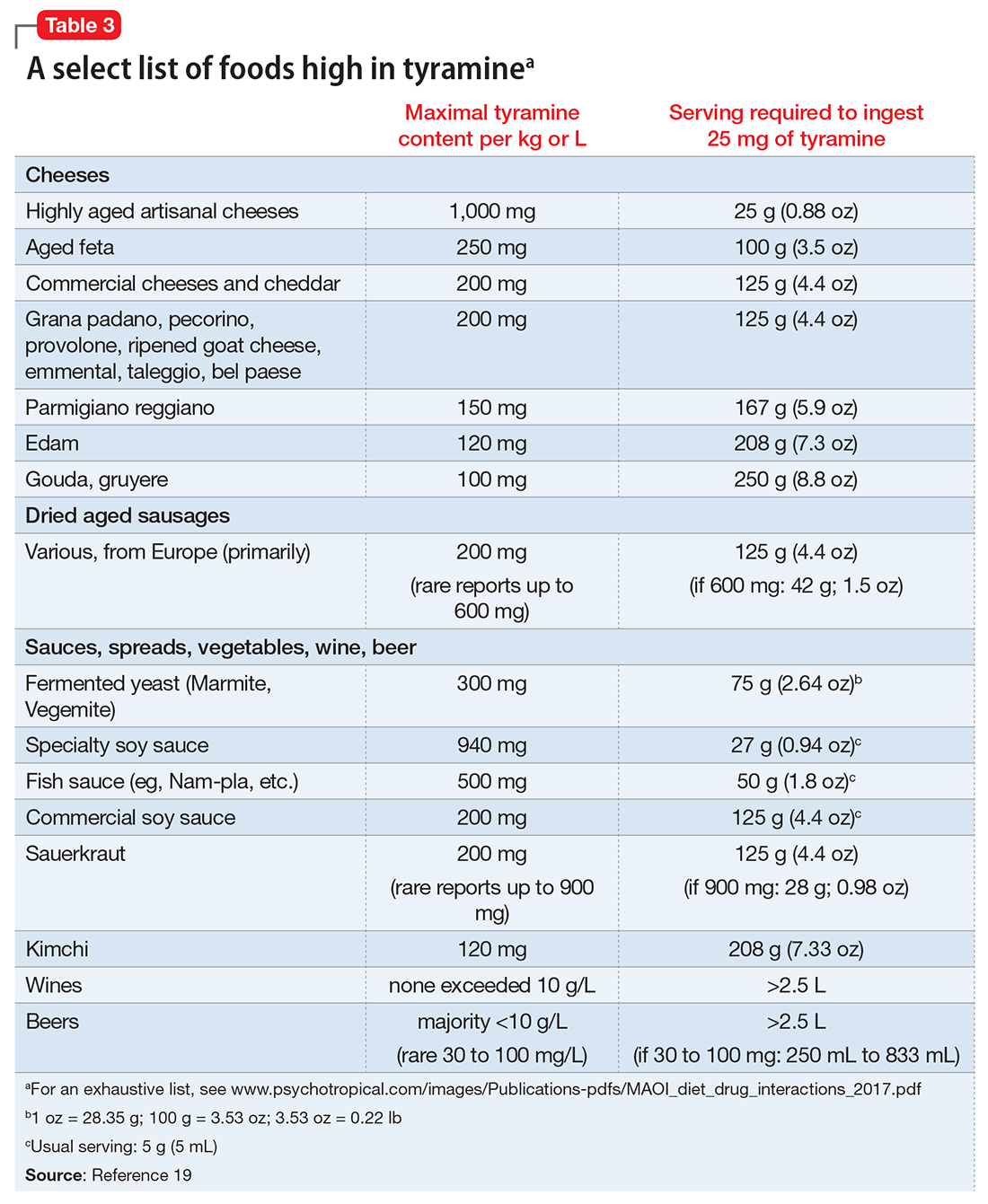

Also, tell patients that if a food is unfamiliar and highly aged or fermented, they should avoid it until they can further inquire about it. In a review, Gillman19 provides the tyramine content of an exhaustive list of cheeses, aged meats, and sauces (see Related Resources). For other products, patients often can obtain information directly from the manufacturer. In many parts of the world, assays for tyramine content are required as a demonstration of adequate product safety procedures. Even the most highly aged cheeses with a tyramine content of 1,000 g/kg can be enjoyed in small amounts (<1 oz), and most products would require heroic intake to achieve clinically significant tyramine ingestion (Table 319).

Improved education can clarify the risks

Medications such as lithium, clozapine, and MAOIs have a proven record of efficacy, yet often are underused due to fears engendered by lack of systematic training. A recent initiative in New York thus aimed to increase rates of