Valbenazine for tardive dyskinesia

Tetrabenazine, a molecule developed in the mid-1950s to improve on the tolerability of reserpine, was associated with significant adverse effects such as orthostasis.6 Like reserpine, tetrabenazine subsequently was found to be effective for TD7 but without the peripheral adverse effects of reserpine. However, the kinetics of tetrabenazine necessitated multiple daily doses, and required CYP2D6 genotyping for doses >50 mg/d.8

Receptor blocking. The mechanism that differentiated reserpine’s and tetrabenazine’s clinical properties became clearer in the 1980s when researchers discovered that transporters were necessary to package neurotransmitters into the synaptic vesicles of presynaptic neurons.9 The vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT) exists in 2 isoforms (VMAT1 and VMAT2) that vary in distribution, with VMAT1 expressed mainly in the peripheral nervous system and VMAT2 expressed mainly in monoaminergic cells of the central nervous system.10

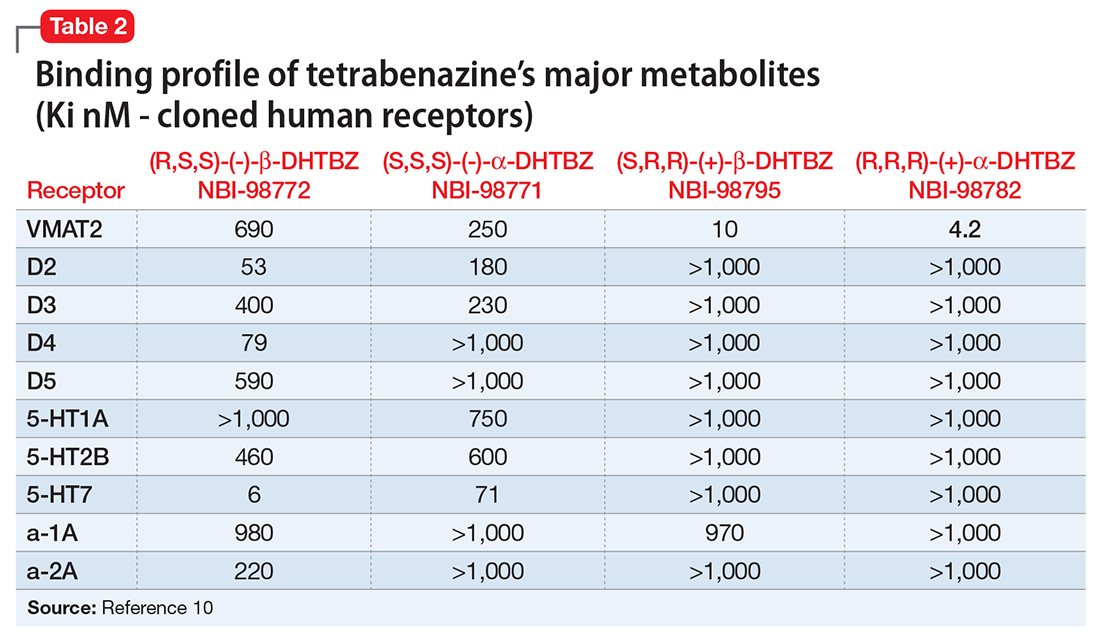

Tetrabenazine’s improved tolerability profile was related to the fact that it is a specific and reversible VMAT2 inhibitor, while reserpine is an irreversible and nonselective antagonist of both VMAT isoforms. Investigation of tetrabenazine’s metabolism revealed that it is rapidly and extensively converted into 2 isomers, α-dihydrotetrabenazine (DH-TBZ) and β-DH-TBZ. The isomeric forms of DH-TBZ have multiple chiral centers, and therefore numerous forms of which only 2 are significantly active at VMAT2.3 The α–DH-TBZ isomer is metabolized via CYP2D6 and 3A4 into inactive metabolites, while β-DH-TBZ is metabolized solely via 2D6.3 Because of the short half-life of DH-TBZ when generated from oral tetrabenazine, the existence of 2D6 polymorphisms, and the predominant activity deriving from only 2 isomers, a molecule was synthesized (valbenazine), that when metabolized would slowly be converted into the most active isomer of α–DH-TBZ designated as NBI-98782 (Table 2). This slower conversion to NBI-98782 from valbenazine (compared with its formation from oral tetrabenazine) yielded improved kinetics and permitted once-daily dosing; moreover, because the metabolism of NBI-98782 is not solely dependent on CYP2D6, the need for genotyping was removed. Neither of the 2 metabolites from valbenazine NBI-98782 and NB-136110 have significant affinity for targets other than VMAT2.11

Use in tardive dyskinesia. Recommended starting dosage is 40 mg once daily with or without food, increased to 80 mg after 1 week, based on the design and results from the phase-III clinical trial.12 The FDA granted breakthrough therapy designation for this compound, and only 1 phase-III trial was performed. Valbenazine produced significant improvement on the AIMS, with a mean 30% reduction in AIMS scores at the Week 6 endpoint from baseline of 10.4 ± 3.6.2 The effect size was large (Cohen’s d = 0.90) for the 80-mg dosage. Continuation of 40 mg/d may be considered for some patients based on tolerability, including those who are known CYP2D6 poor metabolizers, and those taking strong CYP2D6 inhibitors. Patients taking strong 3A4 inhibitors should not exceed 40 mg/d. The maximum daily dose is 40 mg for those who have moderate or severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh score, 7 to 15). Dosage adjustment is not required for mild to moderate renal impairment (creatinine clearance, 30 to 90 mL/min).