Improved Pharmacogenomic Testing Process for Veterans in Outpatient Settings by Clinical Pharmacist Practitioners

Background: Pharmacogenomic Testing for Veterans (PHASER) is a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) program that offers a 16-gene laboratory test panel to patients. Pharmacogenomic testing results may improve patient care by providing patient-specific information on how effective a medication may be or identifying increased risks for adverse drug effects. A VA Central Ohio Healthcare System Pharmacy department initiative sought to increase outpatient PHASER ordering by clinical pharmacist practitioners (CPPs).

Observations: CPPs were surveyed to address the current process and perceived barriers. Barriers identified by CPPs included a lack of clinician education materials, standardized screening process, comfort with PHASER ordering and education, support for the initiative, time constraints preventing patient education and ordering, higher priority clinical needs, forgetting to order, and increased workload and burnout. A gap analysis was used to create a new workflow with the goal of increasing PHASER orders by 50% after 3 months. The new workflow included prefilled templates, education, and visual reminders. PHASER orders increased from 87 preimplementation to 196 postimplementation, a 125% increase.

Conclusions: This quality improvement initiative resulted in an increase in PHASER orders and a clearly defined process. Perceived barriers were identified, and process changes attempted to address them in a sustainable way.

Peer-review, evidence-based, detailed gene/drug clinical practice guidelines suggest that genetic variations can impact how individuals metabolize medications, which is sometimes included in medication prescribing information.1-3 Pharmacogenomic testing identifies genetic markers so medication selection and dosing can be tailored to each individual by identifying whether a specific medication is likely to be safe and effective prior to prescribing.4

Pharmacogenomics can be a valuable tool for personalizing medicine but has had suboptimal implementation since its discovery. The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system reviewed the implementation of the Pharmacogenomic Testing for Veterans (PHASER) program. This review identified clinician barriers pre- and post-PHASER program implementation; staffing issues, competing clinical priorities, and inadequate PHASER program resources were the most frequently reported barriers to implementation of pharmacogenomic testing.5

Another evaluation of the implementation of the PHASER program that surveyed VA patients found that patients could be separated into 3 groups. Acceptors of pharmacogenomic testing emphasized potential health benefits of testing. Patients that declined testing often cited concerns for genetic information affecting insurance coverage, being misused, or being susceptible to data breach. The third group—identified as contemplators—reported the need for clinician outreach to impact their decision on whether or not to receive pharmacogenomic testing.6 These studies suggest that removing barriers by providing ample pharmacogenomics resources to clinicians, in addition to detailed training on how to offer and follow up with patients regarding pharmacogenomic testing, is crucial to successful implementation of the PHASER program.

PHASER

In 2019, the VA began working with Sanford Health to establish the PHASER program and offer pharmacogenomic testing. PHASER has since expanded to 25 VA medical centers, including the VA Central Ohio Healthcare System (VACOHCS).7,8 Pharmacogenomic testing through PHASER is conducted using a standardized laboratory panel that includes 12 different medication classes.9 The drug classes include certain anti-infective, anticoagulant, antiplatelet, cardiovascular, cholesterol, gastrointestinal, mental health, neurological, oncology, pain, transplant, and other miscellaneous medications. Medications are correlated to each class and assessed for therapeutic impacts based on gene panel results.

Clinical recommendations for medication-gene interactions can range from monitoring for increased risk of adverse effects or therapeutic failure to recommending avoiding a medication. For example, patients who test positive for the HLA-B gene have significantly increased risk of hypersensitivity to abacavir, an HIV treatment.10

Similarly, patients who cannot adequately metabolize cytochrome P450 2C19 should consider avoiding clopidogrel as they are unlikely to convert clopidogrel to its active prodrug, which reduces its effectiveness.11 Pharmacists can play a critical role educating patients about pharmacogenomic testing, especially within hematology and oncology.12 Patients can benefit from this testing even if they are not currently taking medications with known concerns as they could be prescribed in the future. The SLCO1B1 gene-drug test, for example, can identify risk for statin-associated muscle symptoms.13

Clinical pharmacist practitioners (CPPs) can increase access to genetic testing because they interact with patients in a variety of settings and can order this laboratory test.12,14 Recent research has demonstrated that most VA patients carry ≥ 1 genetic variant that may influence medication decisions and that half of veterans are prescribed a medication with known gene-drug interactions.15 CPP ordering of pharmacogenomic tests at the VACOHCS outpatient clinic was evaluated through collection of baseline data from March 8, 2023, to September 8, 2023. A goal was identified to increase orders by 50% for a patient care quality improvement initiative and use CPPs to increase access to pharmacogenomic testing. The purpose of this quality improvement initiative was to expand access to pharmacogenomic testing through process implementation and improvement within CPP-led clinic settings.

Gap Analysis

Lean Six Sigma A3 methodology was used to identify ways to increase the use of pharmacogenomic testing for veterans at VACOHCS and develop an improved process for increased ordering of pharmacogenomic testing. Lean Six Sigma A3 methodology is a stepwise approach to process improvement that helps identify gaps in efficiency, sustainable changes, and eliminate waste.16 Baseline data were collected from March 8, 2023, to September 8, 2023, to determine the frequency of CPPs ordering pharmacogenomic laboratory panels during clinic appointments. The ordering of pharmacogenomic panels was monitored by the VACOHCS PHASER coordinator.

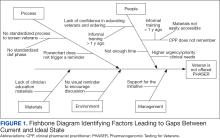

CPPs were surveyed to identify perceived barriers to PHASER implementation. A gap analysis was conducted using Lean Six Sigma A3 methodology. Gap analyses use lean tools such as a Fishbone Diagram to illustrate and identify the gap between current state and ideal state. (Figure 1).The following barriers were identified: lack of clinician education materials, lack of a standardized patient screening process, time constraints on patient education and ordering, higher priority clinical needs, forgetting to order, lack of comfort with pharmacogenomics ordering and education, lack of support for the initiative, and increased workload and burnout. Among these perceived barriers, higher priority clinical needs, forgetting to order, and time constraints ranked highest in importance among CPPs.

In line with Lean Six Sigma A3 methodology, several tests of change were used to improve pharmacogenomic testing ordering. These changes focused on increasing patient and clinician awareness, facilitating discussion, educating clinicians, and simplifying documentation to ease time constraints. Several strategies were employed postimplementation (Figure 2). Prefilled templates simplified documentation. These templates helped identify patients without pharmacogenomic testing, provided reminders, and saved documentation time during visits. CPPs also received training and materials on PHASER ordering and documentation within encounter notes. Additionally, patient-directed advertisements were displayed in CPP examination rooms to help inspire and facilitate discussion between veterans and CPPs.

Process Improvement Data

The quality improvement project goal was to increase PHASER orders by 50% after 3 months. PHASER orders increased from 87 at baseline (March 8, 2023, to September 8, 2023) to 196 during the intervention (November 16, 2023, to February 16, 2024), a 125% increase. Changes were consistent and sustained with 65 orders the first month, 67 orders the second month, and 64 orders the third month.

Discussion

Using Lean Six Sigma A3 methodology for a quality improvement process to increase PHASER orders by CPPs revealed barriers and guided potential solutions to overcome these barriers. Interventions included additional CPP training and ordering, tools for easier identification of potential patients, documentation best practices, patient-directed advertisements to facilitate conversations. These interventions required about 8 hours for preparation, distribution, development, and interpretation of surveys, education, and documentation materials. The financial impact of these interventions was already included in allotted office materials budgeted and provided. Additional funding was not needed to provide patient-directed advertisements or education materials. The VACOHCS pharmacogenomics CPP discusses PHASER test results with patients at a separate appointment.

Future directions include educating other CPPs to assist in discussing results with veterans. Overall, the changes implemented to improve the PHASER ordering process were low effort and exemplify the ease of streamlining future initiatives, allowing for sustained optimal implementation of pharmacogenomic testing.

Conclusions

A quality improvement initiative resulted in increased PHASER orders and a clearly defined process, allowing for a continued increase and sustained support. Perceived barriers were identified, and the changes implemented were often low effort but exhibited a sustained impact. The insights gleaned from this process will shape future process development initiatives and continue to sustain pharmacogenomic testing ordering by CPPs. This process will be extended to other VACOHCS clinical departments to further support increased access to pharmacogenomic testing, reduce medication trial and error, and reduce hospitalizations from adverse effects for veterans.