UPDATE: MINIMALLY INVASIVE SURGERY

When a problematic cervix or distorted anatomy makes it impossible to enter the uterus for hysteroscopy or other office procedures, a few good tools and techniques can help.

IN THIS ARTICLE

Vaginal route is clearly effective in premenopausal women

In premenopausal women, several recent randomized clinical trials show that vaginal misoprostol, administered before hysteroscopy, not only decreases pain and the force and amount of dilation needed, but also reduces complications of cervical dilation.8 As Uckuyu and colleagues observe, these findings are consistent in nulliparous women who have a history of cesarean delivery and who receive 400 μg of vaginal misoprostol 6 to 12 hours before hysteroscopy.

Several studies found no improvement in ease of dilation or operative time in menopausal women who received misoprostol before hysteroscopy.9,10 However, in their randomized, placebo-controlled trial, da Costa and colleagues found that women who received 200 μg of vaginal misoprostol 8 hours before hysteroscopy had a significant decrease in intraprocedural pain associated with cervical dilation.

Recommended protocol

For women at significant risk of cervical stenosis, give 400 μg of intravaginal misoprostol approximately 12 hours before the scheduled procedure. The patient should begin round-the-clock use of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) an hour before insertion of the misoprostol tablets.

Side effects of vaginal and oral misoprostol include occasional diarrhea, abdominal cramping, uterine bleeding, and pyrexia. These effects are usually mild and limited.8 Concomitant administration of NSAIDs reduces or eliminates these side effects.

Although you may sometimes find an incompletely dissolved tablet within the vagina, active medication usually has been absorbed, leaving the less soluble vehicle behind.

Frequent causes of stenosis include:

- Loop electrosurgical excision procedure, conization, and laser vaporization—In one series, 43% of cases of cervical stenosis resulted from one of these procedures, with a recurrence rate of 14%.11

- Scarring of the external os—Common in the parous cervix. Usually, only minimal dilation is needed; the remainder of the cervix is traversed easily.

- Narrow or closed external os—Common in menopausal women and increasingly common in nulligravid and nulliparous women as the rate of elective cesarean delivery rises. In these cases, both the endocervical canal and internal os are narrow, necessitating dilation through the entire length of the cervix.

- Genital atrophy—In postmenopausal women, cervical stenosis as a result of genital atrophy is associated with pain upon cervical dilation. The situation generally necessitates local anesthesia.12

When mechanical dilation is necessary, a few prerequisites can make a difference

By assessing each patient carefully, the gynecologist can customize the intervention. Accordingly, it is wise to have multiple types of dilators accessible to accommodate varying clinical needs and anatomic scenarios.

Begin by stabilizing the cervix. Use of a single-toothed tenaculum, placed on the anterior lip of the cervix, has several advantages. Countertraction against the dilating instrument can facilitate more controlled placement of the dilator, preventing perforation of the uterus. This maneuver is especially useful when the cervical canal and internal os are tight or resistant.

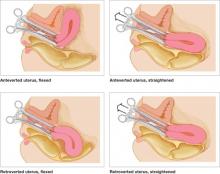

Use of a tenaculum when placing a hysteroscope produces a similar result and can add an element of safety to uterine access, especially when the uterus is significantly flexed (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1 Straighten a flexed uterus before dilating the cervix

When the uterus is flexed, creating acute angulation at the cervicouterine junction, it can be difficult to move the dilator through the internal os. By placing a tenaculum at the 12 o’clock position on the cervix of an anteverted uterus, or 6 o’clock on a retroverted uterus, and applying outward traction, you can straighten the distorted canal.

A local anesthetic can help

It is helpful to administer a local anesthetic before placing a penetrating instrument such as the tenaculum. Patients are usually grateful for the extra few minutes taken to ensure their comfort.

If the cervix is resistant, or the patient is uncomfortable, after initial attempts to dilate the cervix, consider placing a paracervical or intracervical stromal local anesthetic. Lidocaine 1% has a rapid onset of action, reaching peak effectiveness in just a few minutes, with a duration of approximately 60 minutes. Bupivacaine 0.25% has a slightly slower onset of action (8–10 minutes), but offers long duration—about 240 minutes.

Place 5 to 10 cc of local anesthetic paracervically at the 4 and 8 o’clock positions. The choice of anesthetic depends on the procedure. For example, a nulligravid patient may benefit from bupivacaine because cervical dilation can cause significant and prolonged cramping. Bupivacaine is more potent than lidocaine and, therefore, potentially more cardiotoxic, so caution is advised.

Used correctly, local anesthetic facilitates cervical dilation.

Types of dilators

Many instruments are available. Be familiar with the benefits and shortcomings of each to achieve successful cervical dilation in the office.

Lacrimal-duct dilators. These instruments have long been used by gynecologists for cervical access when the closed external os is no more than a tiny dimple. These ophthalmologic instruments come in diameters smaller than 1 mm and allow the closed menopausal cervix to be dilated enough to allow placement of more traditional instruments (FIGURE 2).