Managing an eclamptic patient

Most Ob/Gyns have little experience managing acute eclampsia, but all maternity units and obstetricians need to be prepared to diagnose and manage this grave threat.

Controlling severe hypertension

The next step is to reduce blood pressure to a safe range. The objective: to preserve cerebral autoregulation and prevent congestive heart failure without compromising cerebral perfusion or jeopardizing uteroplacental blood flow, which is already reduced in many women with eclampsia.1

To these ends, try to keep systolic blood pressure between 140 and 160 mm Hg and diastolic pressure between 90 and 110 mm Hg. This can be achieved with:

- bolus 5- to 10-mg doses of hydralazine,

- 20 to 40 mg labetalol intravenously every 15 minutes, as needed, or

- 10 to 20 mg oral nifedipine every 30 minutes.

Other potent antihypertensive drugs such as sodium nitroprusside or nitroglycerine are rarely needed in eclampsia, and diuretics are indicated only in the presence of pulmonary edema.

Intrapartum management

Maternal hypoxemia and hypercarbia cause fetal heart rate and uterine activity changes during and immediately following a convulsion.

Fetal heart rate changes

These can include bradycardia, transient late decelerations, decreased beat-to-beat variability, and compensatory tachycardia.

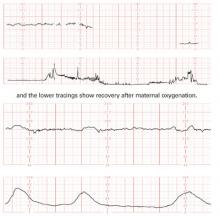

The interval from onset of the seizure to the fall in fetal heart rate is approximately 5 minutes (FIGURE 1). Transitory fetal tachycardia frequently occurs after the prolonged bradycardia. The loss of beat-to-beat variability, with transitory late decelerations, occurs during the recovery phase.

The mechanism for the transient fetal bradycardia may be intense vasospasm and uterine hyperactivity, which may decrease uterine blood flow. The absence of maternal respiration during the convulsion may also contribute to fetal heart rate changes.

Since the fetal heart rate usually returns to normal after a convulsion, other conditions should be considered if an abnormal pattern persists.

In some cases, it may take longer for the heart rate pattern to return to baseline if the fetus is preterm with growth restriction.

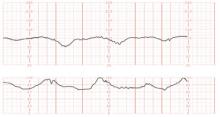

Placental abruption may occur after the convulsion and should be suspected if fetal bradycardia or repetitive late decelerations persist (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 1 Fetal response to a convulsion The top 2 tracings show fetal bradycardia during an eclamptic convulsion

FIGURE 2 Abruptio placentae Repetitive late decelerations secondary to abruptio placentae, necessitating cesarean section

Uterine activity

During a convulsion, contractions can increase in frequency and tone. The duration of increased uterine activity varies from 2 to 14 minutes.

These changes usually resolve spontaneously within 3 to 10 minutes following the termination of convulsions and correction of maternal hypoxemia (FIGURE 1).

If uterine hyperactivity persists, suspect placental abruption (FIGURE 2).

Do not rush to cesarean

It benefits the fetus to allow in utero recovery from the maternal convulsion, hypoxia, and hypercarbia before delivery. However, if the bradycardia and/or recurrent late decelerations persist beyond 10 to 15 minutes despite all efforts, suspect abruptio placentae or nonreassuring fetal status.

Once the patient regains consciousness and is oriented to name, place, and time, and her convulsions are controlled and condition stabilized, proceed with delivery.

Choosing a delivery route

Eclampsia is not an indication for cesarean. The decision to perform a cesarean should be based on fetal gestational age, fetal condition, presence of labor, and cervical Bishop score. I recommend:

- Cesarean section for women with eclampsia before 30 weeks’ gestation who are not in labor and whose Bishop score is below 5.

- Vaginal delivery for women in labor or with rupture of membranes, provided there are no obstetric complications.

- Labor induction with oxytocin infusion or prostaglandins in all women at or after 30 weeks, regardless of the Bishop score, and in women before 30 weeks when the Bishop score is 5 or above.

Maternal pain relief

During labor and delivery, systemic opioids or epidural anesthesia can provide pain relief—the same recommendations as for women with severe preeclampsia.

For cesarean delivery, an epidural, spinal, or combined techniques of regional anesthesia are suitable.

Do not use regional anesthesia if there is coagulopathy or severe thrombocytopenia (platelet count less than 50,000/mm3). In women with eclampsia, general anesthesia increases the risk of aspiration and failed intubation due to airway edema, and is associated with marked increases in systemic and cerebral pressures during intubation and extubation.

Women with airway or laryngeal edema may require awake intubation under fiber optic observation, with tracheostomy immediately available.

Changes in systemic or cerebral pressures may be attenuated by pretreatment with labetalol or nitroglycerine injections.

Postpartum management

After delivery, women with eclampsia require close monitoring of vital signs, fluid intake and output, and symptoms for at least 48 hours.

Risk of pulmonary edema

These women usually receive large amounts of intravenous fluids during labor, delivery, and postpartum. In addition, during the postpartum period, extracellular fluid mobilizes, leading to increased intravascular volume.