Preventing BRCA-related cancers: The case for oophorectomy

The team that conducted the recent prospective trial of risk-reducing surgery versus surveillance reviews the evidence, plus surgical technique, psychosocial factors, use of estrogen after surgery, and insurance issues.

TABLE

Breast and ovarian cancer risk-reduction strategies for women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations

| TYPE OF CANCER | STRATEGY | ALSO CONSIDER … |

|---|---|---|

| Breast | Monthly self-examination beginning at age 18 | Imaging Breast ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging |

| 2-4 physician examinations per year, starting at age 25 | Risk–reducing surgery Mastectomy, no earlier than mid-20s | |

| Annual mammography beginning at age 25 | Salpingo-oophorectomy, after age 35 and completion of childbearing | |

| Chemoprevention Tamoxifen. Need to discuss conflicting reports on efficacy | ||

| Ovarian | CA 125 and ultrasound twice yearly, starting at age 35 | Salpingo-oophorectomy After age 35 and the completion of childbearing |

| Chemoprevention Oral contraceptives, though they may be associated with an increased risk of breast cancer | ||

| Source: Adapted from Scheuer et al28 | ||

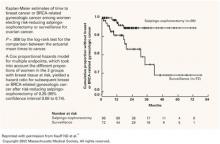

FIGURE 1 Reduction in cancer cases associated with salpingo-oophorectomy

Reprinted with permission from Kauff ND et al.18

Copyright 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Good technique and pathologic review may prevent post-oophorectomy cancer

There are 3 theories about the origin of primary peritoneal cancer after oophorectomy:

- The cancer represents undetected occult cancer present at the time of risk-reducing surgery.

- It represents cancer arising in an ovarian remnant left behind after risk-reducing surgery.

- The peritoneal cancer arises de novo from the peritoneal surface epithelium.

Reasonable evidence supports each of these theories; thus, each may play some role in the incidence of “peritoneal” cancer after risk-reducing surgery.21-23

While surgical technique and detailed pathologic review are unlikely to decrease the incidence of de novo peritoneal cancer, they may play a substantial role in reducing ovarian and related cancers after risk-reducing surgery.

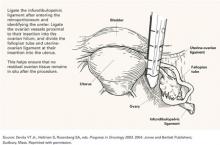

Surgical requirements. Obviously, if a surgery is to be risk-reducing, as much as possible of the tissue at risk should be removed. To do so effectively, the surgeon should be comfortable operating in the retroperitoneum so that the infundibulopelvic ligament can be ligated sufficiently proximal from the ovarian hilum to minimize the possibility of an ovarian remnant. Similarly, if a salpingo-oophorectomy without hysterectomy is to be performed, the fallopian tube should be amputated as close as possible to the uterine cornua (FIGURE 2).

Laparoscopy versus open surgery. RRSO can be performed using either a laparoscopic or open approach. The appropriate choice is best determined by the patient’s history, associated comorbid conditions, need for additional procedures, and experience of the surgeon. At our institution, in the absence of contraindications, we generally offer a laparoscopic approach due to its decreased morbidity.

Concomitant hysterectomy? An area of substantial controversy is whether the uterus should be removed at the time of RRSO. In most studies exploring this issue, hereditary breast-ovarian cancer syndrome does not appear to be associated with an increased risk of uterine cancer.24 However, there is concern that the portion of interstitial fallopian tube left behind after salpingo-oophorectomy may be at risk for malignant transformation.25,26

In our series, almost 90% of risk-reducing procedures were salpingo-oophorectomies without hysterectomy. If there is an additional benefit to concomitant hysterectomy, it has yet to be demonstrated by clinical trials.

In several studies, a patient’s level of anxiety was more important than objective cancer risk in the choice of RRSO.

Close pathologic scrutiny advised. Microscopic cancer may be found in 2% to 4% of RRSO specimens upon careful pathologic review.21,27,28 Thus, it is essential that the ovaries and fallopian tubes are sectioned in their entirety and examined by an experienced gynecologic pathologist to minimize the chance that microscopic cancer goes undetected.

It is not clear whether cytology should be routinely done at the time of risk-reducing surgery. A single report documents malignant cells in a woman with a BRCA1 mutation and no obvious foci of malignancy despite hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and staging.29 Pending further studies, we routinely send cytology for review.

FIGURE 2 Careful surgical ligation and division to eliminate residual tissue

Source: Devita VT Jr., Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, eds. Progress in Oncology 2003. 2004: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; Sudbury, Mass. Reprinted with permission.

When no BRCA mutation is present

Most of the data cited thus far apply to women with documented BRCA mutations. There is much less information about the relative risks and benefits of RRSO in women with a personal or family history of breast or ovarian cancer who lack a documented BRCA mutation.

Although RRSO may be appropriate for some of these women, in 2004 it is not the standard of care to recommend RRSO to all individuals with a personal or family history suggestive of an inherited predisposition to ovarian cancer. These patients are best managed by an interdisciplinary team of gynecologists, gynecologic oncologists, and clinical geneticists, all with experience caring for women who may have an inherited predisposition.