Cone biopsy: perfecting the procedure

When colposcopy and cervical biopsy are inadequate in evaluating cervical dysplasia, cone biopsy of the cervix often will be both diagnostic and therapeutic.

Technique

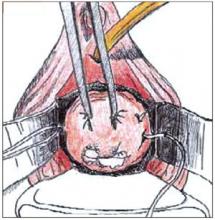

Traditionally, the first step in performing a cone biopsy is to place sutures lateral to the cervix to decrease bleeding (Figure 1). While many surgeons believe that these sutures have a beneficial effect on hemosta-sis, others have not found them to be necessary.4 And although cone biopsy typically is performed under regional or general anesthesia, I have found that IV sedation and injection of a local anesthetic are adequate for most cone biopsies.

Begin the procedure by placing either a posterior weighted speculum (for a cold-knife cone) or an insulated speculum (for electrocautery) into the vagina. Then inject a premixed solution of 2% xylocaine and epi-nephrine in a concentration of 1:200,000 into the cervical stroma at 12 o’clock outside the intended margin of the cone biopsy. Then grasp this tissue with a single-tooth tenacu-lum. Inject 5 to 10 cc of the solution para-cervically at 3 o’clock and again at 9 o’clock. I typically use a total of 20 to 30 cc to maintain hemostasis. Alternatively, the anesthetic can be infiltrated into the subepithelial stroma circumferentially around the ectocervix.

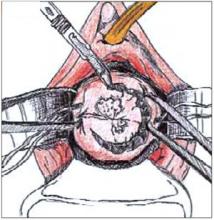

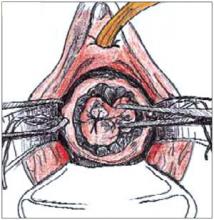

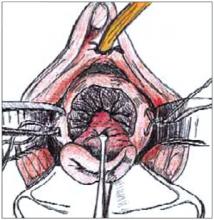

To perform a cold-knife cone, use a #11 surgical blade to begin a circular incision starting at 12 o’clock on the face of the cervix, angling the tip of the blade toward the endocervical canal (Figure 2). Use a uterine sound to mark a depth of 2 cm within the endo-cervical canal, typically the most cephalad margin of the cone. The goal is to remove a single specimen that includes the entire transformation zone and distal endocervical canal (Figure 3). After removing the cone, perform an endocervical curettage to collect an additional specimen. Apply light cautery to the edges of the cervical bed, as well as any bleeding points (Figure 4). Place 1 interrupted suture (I prefer 2-0 polyglactin) in each quadrant of the face of the cervix, starting from outside the margin of the cone and exiting near the cervical os. Then insert the suture near the cervical os and exit outside the margin of the cone. Tying these sut ures everts the cervical os to a degree and keeps the transformation zone closer to the external surface of the cervix, making it easier to find when performing future colposcopies.

Electroexcision with a fine-needle electrode is performed with a blend-1 waveform using 18 watts of power.5 Perform the excision using the “cut” button on the bovie handpiece and then use the leading edge of the electrical arc to incise the tissue. (It is best to use the arc, i.e., visible spark, to do the cutting rather than the tip of the instrument, which may “stick” to surrounding tissues.) Make a full circle to a depth of about 7 mm to outline the ectocervical cone margins. Then “pull down” the stroma on the edge of the specimen with a skin hook to continue the dissection parallel to the long axis of the endocervical canal to a depth of 1.5 to 2.0 cm. I excise the “base” of the cone with scissors to minimize any cautery effect at the endocervical margin. Achieve hemostasis by electrofulgurating the bleeding vessels using 30 to 40 watts of power in the coagulation mode. Monsel solution or paste then can be applied as needed. This technique is similar to CO2 laser conization, only it is easier to learn and quicker to perform.

FIGURE 1

Begin the cone biopsy by placing lateral sutures at the cervicovaginal junction to decrease bleeding.

FIGURE 2

Use a #11 surgical blade to make the circular incision, angling the tip of the blade toward the endocervical canal.

FIGURE 3

Grasp the specimen, including the entire transformation zone and distal endocervical canal, with an Allis clamp.

FIGURE 4

Complete the cone excision by cutting across endocervix. Apply light cautery to the edges of the cervical bed.

Follow-up

Postoperatively, patients should undergo cytologic screening every 4 months for 2 years to identify persistent or recurrent disease. Patients with positive cone biopsy margins face the highest risk of persistent or recurrent cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN). Although there is considerable variation, studies generally have reported a 30% incidence of positive margins. The incidence of recurrent dysplasia when the margins are positive has been reported to be as high as 50%.6,7

In women with positive margins, colposcopy and cervical and endocervical cytology are an important part of the follow-up. I perform an endocervical curettage, in addition to a Pap smear, at each interval visit during the first year postoperatively and perform colposcopy at the 6- and 12- month visits. After 2 years of follow-up with normal results, cytologic screening should be performed annually, per routine care.