HIV in Pregnancy: An Update

Remarkable progress has been made over the past 30-plus years in the identification of the human immunodeficiency virus, in the development of drugs to treat HIV infection, and in providing access and assuring adherence to these increasingly effective therapies. As a result, we can now offer women with HIV infection a significantly improved prognosis as well as a very high likelihood of having children who will not be infected with HIV.

While HIV infection is still an incurable, lifelong disease, it has in many ways become a chronic disease just like many other chronic diseases – a status that just a generation ago would have been a pipe dream. Today when I see a patient who has hypertension, diabetes, and HIV infection, I am often more worried about managing the hypertension and diabetes than I am about managing the HIV.

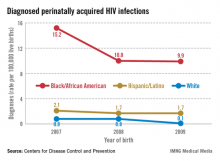

In my state of New York, for example, the number of babies born with HIV infection 15 years ago was approximately 100; in 2010, this number was 3.

Whether we practice in an area of high or low prevalence, we each have a responsibility to identify HIV-infected women and, in the context of pregnancy, to ensure that each patient’s prognosis is optimized, and perinatal transmission is prevented by bringing her viral load to an undetectable level. In cases in which an uninfected woman is considering pregnancy and her partner is HIV infected, periconception administration of antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis is a new and promising tool.

Identifying patients

None of these benefits can be provided to HIV-infected women if their status is unknown. Just as we have to measure blood pressure in order to be able to treat hypertension, we must ensure that women in our practices know their HIV status so that they can avail themselves of the remarkable advances that have been made in the care of HIV infection and the prevention of mother-to-child transmission. Testing appropriately is part of our role.

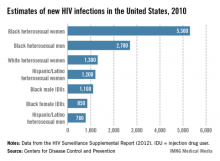

Certainly, HIV incidence and risk for infection vary across the United States; there are dramatic differences in risk, for instance, between Des Moines, where prevalence is low, and Washington, D.C., where almost 3% of the population is infected with HIV. Still, regardless of geography, we must appreciate that the impact of the epidemic on women has grown significantly over time, such that women now account for approximately one in four people living with HIV, according to the CDC.

What is especially important for us to appreciate is the fact that a sizable portion of all people with HIV still do not know their HIV status. The CDC estimates that approximately 18% of all HIV-infected individuals are unaware of their status.

A significant percentage of the children who are infected, moreover, were born to women whose status was unknown. According to the CDC, approximately 27% of the mothers of HIV-infected infants reported from 2003 to 2007 were diagnosed with HIV after delivery, and only 29% of the mothers of infected infants received antiretroviral therapy (ART) during pregnancy.

The CDC, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the American Academy of Pediatrics, and other national organizations have long called for universal prenatal HIV testing to improve the health outcomes of the mother and infant.

On a broader level, the approach to testing has evolved. In 2006, the CDC moved away from targeted risk-based HIV testing recommendations and advised routine opt-out testing for all patients aged 13-64 years. The agency concluded that universal testing is more effective largely because many patients found to be infected did not consider themselves to be at risk. ACOG weighed in the following year, also recommending universal testing with patient notification and an opt-out option, which removes the need for detailed, testing-related informed consent.