Does tamoxifen use increase the risk of endometrial cancer in premenopausal patients?

In a large, nationwide retrospective longitudinal cohort study that examined the occurrence of endometrial cancer and other uterine pathology in patients using tamoxifen for treatment of invasive breast cancer compared with breast cancer patients not receiving tamoxifen, the authors found a 3.77-fold increased risk of endometrial cancer in premenopausal patients using tamoxifen. These data conflict with multiple previously published randomized controlled trials that demonstrated an increased risk of endometrial cancer in the postmenopausal population (but not in premenopausal patients). The experts suggest that a study design issue in the recent study may explain these disparate findings.

Methodological concerns

In the study by Ryu and colleagues, we found the definition of premenopausal to be problematic. Ultimately, if patients did not have a diagnosis of menopause in the problem summary list, they were assumed to be premenopausal if they were between the ages of 20 and 50 and not taking an aromatase inhibitor. However, important considerations in this population include the cancer stage and treatment regimens that can and do directly impact menopausal status.

Data demonstrate that early-onset breast cancer tends to be associated with more biologically aggressive characteristics that frequently require adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy.6,7 This chemotherapy regimen is comprised most commonly of Adriamycin (doxorubicin), paclitaxel, and cyclophosphamide. Cyclophosphamide is an alkylating agent that is a known gonadotoxin, and it often renders patients either temporarily or permanently menopausal due to chemotherapy-induced ovarian failure. Prior studies have demonstrated that for patients in their 40s, approximately 90% of those treated with cyclophosphamide-containing chemo-therapy for breast cancer will experience chemotherapy-induced amenorrhea (CIA).8 Although some patients in their 40s with CIA will resume ovarian function, the majority will not.8,9

Due to the lack of reliability in diagnosing CIA, blood levels of estradiol and follicle stimulating hormone are often necessary for confirmation and, even so, may be only temporary. One prospective analysis of 4 randomized neoadjuvant/adjuvant breast cancer trials used this approach and demonstrated that 85.1% of the study cohort experienced chemotherapy-induced ovarian failure at the end of their treatment, with some fluctuating back to premenopausal hormonal levels at 6 and 12 months.10

Furthermore, in the study by Ryu and colleagues, there is no description or confirmation of menstrual patterns in the study group to support the diagnosis of ongoing premenopausal status. Data on CIA and loss of ovarian function, therefore, are critical to the accurate categorization of patients as premenopausal or menopausal in this study. The study also relied on consistent and accurate recording of appropriate medical codes to capture a patient’s menopausal status, which is unclear for this particular population and health system.

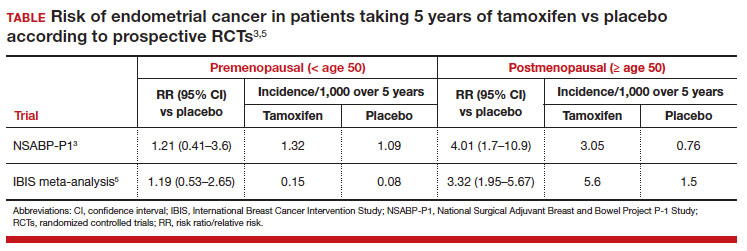

In evaluating prior research, multiple studies demonstrated no increased risk of endometrial cancer in premenopausal women taking tamoxifen for breast cancer prevention (TABLE).3,5 These breast cancer prevention trials have several major advantages in assessing tamoxifen-associated endometrial cancer risk for premenopausal patients compared with the current study:

- Both studies were prospective double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized clinical breast cancer prevention trials with carefully designed and measured outcomes.

- Since these were breast cancer prevention trials, administration of gonadotoxic chemotherapy was not a concern. As a result, miscategorizing patients with chemotherapy-induced menopause as premenopausal would not be expected, and premature menopause would not be expected at a higher rate than the general population.

- Careful histories were required prior to study entry and throughout the study, including data on menopausal status and menstrual and uterine bleeding histories.11

In these prevention trials, the effect of tamoxifen on uterine pathology demonstratedrepeatable evidence that there was a statistically significant increased risk of endometrial cancer in postmenopausal women, but there was no similar increased risk of endometrial cancer in premenopausal women (TABLE).3,5 Interestingly, the magnitude of the endometrial cancer risk found in the premenopausal patients in the study by Ryu and colleagues (RR, 3.77) is comparable to that of the menopausal group in the prevention trials, raising concern that many or most of the patients in the treatment group assumed to be premenopausal may have indeed been “menopausal” for some or all the time they were taking tamoxifen due to the possible aforementioned reasons. ●

While the data from the study by Ryu and colleagues are provocative, the findings that premenopausal women are at an increased risk of endometrial cancer do not agree with those of well-designed previous trials. Our concerns about categorization bias (that is, women in the treatment group may have been menopausal for some or all the time they were taking tamoxifen but were not formally diagnosed) make the conclusion that endometrial cancer risk is increased in truly premenopausal women somewhat specious. In a Committee Opinion (last endorsed in 2020), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) stated the following: “Postmenopausal women taking tamoxifen should be closely monitored for symptoms of endometrial hyperplasia or cancer. Premenopausal women treated with tamoxifen have no known increased risk of uterine cancer and as such require no additional monitoring beyond routine gynecologic care.”12 Based on multiple previously published studies with solid level 1 evidence and the challenges with the current study design, we continue to agree with this ACOG statement.

VERSHA PLEASANT, MD, MPH; MARK D. PEARLMAN, MD