Telemedicine: Medicolegal aspects in ObGyn

The COVID pandemic increased the use of telemedicine dramatically; what should clinicians keep in mind?

CASE Conclusion

Patient concerns come to the fore

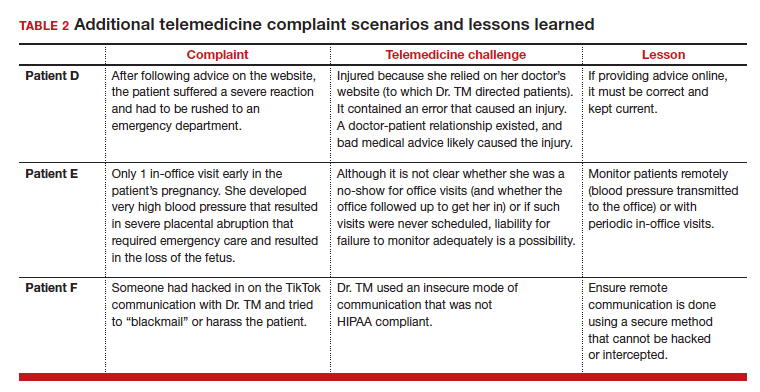

By 2023, Dr. TM started receiving bad news. Patient D called complaining that after following the advice on the website, she suffered a severe reaction and had to be rushed to an emergency department. Patient E (who had only 1 in-office visit early in her pregnancy) notified the office that she developed very high blood pressure that resulted in severe placental abruption, requiring emergency care and resulting in the loss of the fetus. Patient F complained that someone hacked the TikTok direct message communication with Dr. TM and tried to “blackmail” or harass her.

Discussion. Patients D, E, and F represent potential problems of telemedicine practice. Patient D was injured because she relied on her doctor’s website (to which Dr. TM directed patients). It contained an error that caused an injury. A doctor-patient relationship existed, and bad medical advice likely caused the injury. Physicians providing advice online must ensure the advice is correct and kept current.

Patient E demonstrates the importance of monitoring patients remotely (blood pressure transmitted to the office) or with periodic in-office visits. It is not clear whether she was a no-show for office visits (and whether the office followed up on any missed appointments) or if such visits were never scheduled. Liability for failure to monitor adequately is a possibility.

Patient F’s seemingly minor complaint could be a potential problem. Dr. TM used an insecure mode of communication. Although some HIPAA security regulations were modified or suspended during the pandemic, using such an unsecure platform is problematic, especially if temporary HIPAA rules expired. The outcome of the complaint is in doubt.

(See TABLE 2 for additional comments on patients D, E, and F.)

Out-of-state practice

Dr. TM treated 3 out-of-state residents (D, E, and F) via telemedicine. Recently Dr. TM received a complaint from the State Medical Licensure Board for practicing medicine without a license (Patient D), followed by similar charges from Patient E’s and Patient F’s state licensing boards. He has received a licensing inquiry from his home state board about those claims of illegal practice in other states and incompetent treatment.

Patient D’s pregnancy did not go well. The 1 in-person visit did not occur and she has filed a malpractice suit against Dr. TM. Patient E is threatening a malpractice case because the STI was not appropriately diagnosed and had advanced before another physician treated it.

In addition, a private citizen in Patient F’s state has filed suit against Dr. TM for abetting an illegal abortion (for Patient F).

Discussion. Patients D, E, and F illustrate the risk of even incidental out-of-state practice. The medical board inquiries arose from anonymous tips to all 4 states reporting Dr. TM was “practicing medicine without a license.” Patient E’s home state did have a licensing compact with the adjoining state (ie, Dr. TM’s home state). However, it required physicians to register and file an annual report, which Dr. TM had not done. The other 2 states did not have compacts with Dr. TM’s home state. Thus, he was illegally practicing medicine and would be subject to penalties. His home state also might impose license discipline based on his illegal practice in other states.

Continue to: What’s the verdict?...