Diabetes’ social determinants: What they mean in our practices

More than many other pregnancy complications, diabetes exemplifies the impact of social determinants of health.

The medical management of diabetes during pregnancy involves major lifestyle changes. Diabetes care is largely a patient-driven social experience involving complex and demanding self-care behaviors and tasks.

The pregnant woman with diabetes is placed on a diet that is often novel to her and may be in conflict with the eating patterns of her family. She is advised to exercise, read nutrition labels, and purchase and cook healthy food. She often has to pick up prescriptions, check finger sticks and log results, accurately draw up insulin, and manage strict schedules.

Management requires a tremendous amount of daily engagement during a period of time that, in and of itself, is cognitively demanding.

Outcomes, in turn, are impacted by social context and social factors – by the patient’s economic stability and the safety and characteristics of her neighborhood, for instance, as well as her work schedule, her social support, and her level of health literacy. Each of these factors can influence behaviors and decision making, and ultimately glycemic control and perinatal outcomes.

The social determinants of diabetes-related health are so individualized and impactful that they must be realized and addressed throughout our care, from the way in which we communicate at the initial prenatal checkup to the support we offer for self-management.

Barriers to diabetes self-care

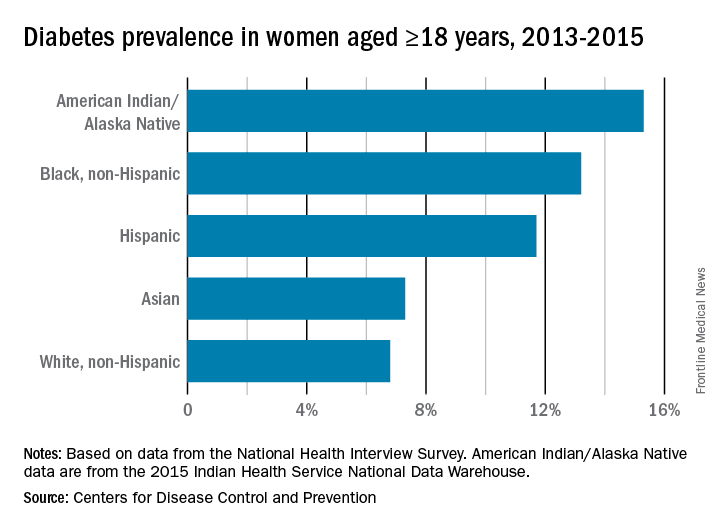

While the incidence of type 2 diabetes is increasing among all social, ethnic, and racial groups, its prevalence among nonpregnant U.S. adults is greatest among racial/ethnic minorities, as well as in individuals with a low-income status. Women who enter pregnancy with preexisting diabetes are more likely to be racial/ethnic minorities.

In pregnancy, minority women (especially Hispanic, but also Asian and non-Hispanic black women), and women with low-income status are similarly predisposed to developing gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).

Social determinants of health are interwoven with inequities stemming from race/ethnicity, income, and other factors that affect outcomes. For example, not only do non-Hispanic black women experience a greater incidence of GDM than non-Hispanic white women, but when they have GDM, they also appear to experience worse pregnancy outcomes compared with white women who also have GDM. In addition, they have a greater likelihood of developing type 2 diabetes after a pregnancy with GDM.

I care for a population that consists largely of minority, low-income women with either gestational or pregestational diabetes. Despite their best intentions and efforts – and despite seemingly high motivation levels – these women struggle to achieve the levels of glycemic control necessary for preventing maternal and fetal complications.

Several years ago, I sought to better understand the barriers to diabetes self-care and behavioral change these women face. Through a series of in-depth, semi-structured interviews with 10 English-speaking women (half with pregestational diabetes) over the course of their pregnancies, we found that the barriers to self-care related to the following: disease novelty, social and economic instability, nutrition challenges, psychological stressors, a failure of outcome expectations, and the burden of disease management (J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015 Aug;26[3]:926-40; J Nutr Educ Behav. 2016 Mar;48[3]:170-80.e1).

Some of these barriers, such as the lack of any prior experience with diabetes (through a family member, for instance) or the inability to believe that behavior change and other treatment could impact her diabetes and her fetus’ health, echoed other limited published data. However, women in our study also appeared to be affected by barriers driven by social instability (e.g., a lack of partner or family support, family conflict, or neighborhood violence), inadequate access to healthy food, and the psychological impact of diabetes.

They often felt isolated and overwhelmed by their diabetes; the condition amplified stresses they were already experiencing and contributed to worsening mental health in those who already had depression or anxiety. In the other direction, women also described how preexisting mental health challenges affected their ability to sustain recommended behavior changes.

However, we also identified factors that empowered women in this community to succeed with their diabetes during pregnancy – these included having prior familiarity and diabetes self-efficacy, being motivated by the health of the fetus or older children, having a supportive social and physical environment, and having the ability to self-regulate or set and achieve goals (J Perinatol. 2016 Jan;36[1]:13-8).

To address these barriers, my group has undertaken a series of projects aimed at improving care for pregnant women with diabetes. We developed a diabetes-specific text message support system, for instance, and are now transitioning this support to an advanced mobile health tool that can help patients beyond our site.