The broad picture of interstitial cystitis

Pelvic floor dysfunction

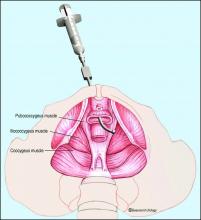

The most important component of the physical exam in patients with the symptoms of frequency, urgency, and pelvic pain – and the most overlooked – is assessment of the levator muscles for tightness and tenderness. Levator pain and trigger points may be identified during the pelvic exam by pressing laterally on the levator complex in each quadrant of the vagina and at the ischial spines. The tension of the muscles and severity of pain should be assessed, and it is helpful to ask the patient if the pain reproduces her normal pelvic pain symptoms.

We’ve found that identifying and treating pelvic floor dysfunction with modalities such as pelvic floor physical therapy with intravaginal myofascial release, intravaginal valium, trigger point injections into the levator complex, pudendal nerve blocks, and neuromodulation can frequently resolve or significantly lessen the patient’s pain and bladder symptoms, suggesting that the diagnosis of IC/BPS was wrong.

Pelvic floor physical therapy works to stretch the contracted anterior pelvic muscles by releasing trigger points and connective tissue restrictions, and by decreasing periurethral tension; it also may decrease neurogenic triggers and central nervous system sensitivity. Kegel exercises will worsen pain in these patients and should be avoided.

When pelvic floor dysfunction is identified, such treatment by a therapist knowledgeable in intravaginal myofascial release is a next reasonable step before any medications or invasive testing, such as bladder hydrodistension, are used.

One of the only National Institutes of Health–funded studies to show benefit of a treatment in an IC population, in fact, was a multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing 10 sessions of myofascial pelvic floor physical therapy with “global therapeutic massage.” Myofascial physical therapy led to significant improvement, compared with the generalized spa-like massage (J Urol. 2012 Jun;187[6]:2113-8).

Our patients with IC/BPS symptoms and pelvic floor dysfunction require 1-2 visits weekly for an average of 12 weeks for tightness and tenderness to be significantly minimized or eliminated. Patients are also prescribed home stretching exercises and advised to use internal vaginal dilators. Most patients will report resolution of their pelvic pain, sexual pain, and bladder symptoms – especially with the combination of physical therapy and trigger point injections. In more severe cases, we may use sacral or pudendal neuromodulation to improve the frequency, urgency and pelvic pain.

Turning to the bladder

When urinary symptoms persist after the completion of pelvic floor therapy, or when pelvic floor dysfunction is not identified in the first place, we proceed with bladder-specific therapies. I will often suggest trials of amitriptyline or hydroxyzine, for instance, and/or changes in hydration and caffeine consumption. I am not a fan of pentosan polysulfate sodium (Elmiron) as it is a very expensive medication that has minimal benefit for the majority of patients.

When conservative therapies do not work, I move to cystoscopy with hydrodistension. The procedure can serve several purposes. It can be diagnostic, enabling us to rule out other potential symptom-causing pathologies, and it can be prognostic, helping us to understand when bladder capacity is severely reduced and to plan treatment. In some patients, it can even be therapeutic. Some of my patients have significant relief of symptoms from a hydrodistension of the bladder once or twice a year.

There is no standard method for performing a hydrodistension. I perform a complete cystoscopy to look for tumors, stones, diverticulum or Hunner’s lesions and, if the bladder is normal in appearance, I proceed with a 2-minute hydrodistension at 80-100 cm of water pressure under anesthesia. The bag is raised above the bladder, allowing the bladder to fill with the force of gravity and the pressures to equalize. The urethra must be compressed so that water doesn’t leak around the cystoscope. After 2 minutes of hydrodistension, the bladder is drained, volume is measured, and the procedure is repeated.

After the hydrodistension, the bladder is reinspected to be certain there is no bladder perforation and to evaluate for diffuse glomerulations (petechial hemorrhages) that are suggestive, but not diagnostic, of IC/BPS.