2016 Update on infectious disease

Recent studies offer new data on treatments for surgical-site infections after cesarean delivery, postpartum endometritis, and chlamydia infection, while a vaccine for hepatitis E with long-term efficacy has promise for reducing occurrence of this common infection in developing countries.

In this article

• Azithromycin vs doxycycline for chlamydia

• Insect repellents to prevent Zika virus

What this evidence means for practiceIn this study, both doxycycline and azithromycin were highly effective (100% and 97%, respectively) for treating chlamydia genital tract infection, and they are comparable in cost. In our opinion, the improved adherence that is possible with single-dose azithromycin, the greater safety in pregnancy, and the excellent tolerability of this drug outweigh its slightly deceased rate of microbiologic cure.

Vaccine effective against hepatitis E for 4+ yearsZhang J, Zhang XF, Huang SJ, et al. Long-term efficacy of a hepatitis E vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(10):914-922.

This study conducted by Zhang and colleagues in Dongtai, China, is an extended follow-up study of the hepatitis E virus (HEV) vaccine (Hecolin; Xiamen Innovax Biotech). A recombinant vaccine directed against HEV genotype 1, Hecolin has been used in China since 2012.

In the initial efficacy study, healthy adults aged 16 to 65 years were randomly assigned to receive either the hepatitis E vaccine (vaccine group, 56,302 participants) or the hepatitis B vaccine (control group, 56,302 participants). Vaccine administration occurred at 0, 1, and 6 months, and participants were followed for a total of 19 months.

Details of the studyThe follow-up study was designed to assess the efficacy, immunogenicity, and safety of the HEV vaccine up to 4.5 years postvaccination. All health care centers (205 village and private clinics) in the study area were enrolled in the program. The treatment assignments of all patients remained double blinded. Unblinding occurred only after the data on safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity had been locked.

A diagnosis of HEV infection was made if at least 2 of the following markers were present: a positive test for immunoglobulin M antibodies against HEV, a positive test for HEV RNA, or a serum concentration of immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies against HEV that was at least 4 times higher than previously measured at any time during the same illness. Vaccine immunogenicity was assessed by testing serum samples for IgG antibodies against HEV at regular intervals after the vaccination was given.

Over the 4.5-year study period, 7 cases of hepatitis E occurred in the vaccine group, and 53 in the control group. Vaccine efficacy was 86.8% (P<.001) in the modified intention-to-treat analysis. Among patients who received 3 doses of HEV vaccine and who were seronegative at the start of the study, 87% maintained antibodies against HEV for 4.5 years. Within the control group, HEV titers developed in 9% of participants. The vaccine and control groups had similar rates of adverse events.

The authors concluded that the HEV vaccine induced antibodies against hepatitis E that lasted up to 4.5 years. Additionally, 2 doses of vaccine induced slightly lower levels of antibody than those produced by 3 doses of the vaccine. Finally, all participants in the vaccine group who developed HEV had antibodies with high or moderate avidity, indicating an anamnestic response from previous immunity. Most participants in the control group who developed HEV, however, had antibodies with low avidity, indicating no previous immunity.

The burden of HEVHepatitis E is a serious infection and is the most common waterborne illness in the world. It occurs mainly in developing countries with limited resources. HEV infection is caused by genotypes 1, 2, 3, or 4, although all 4 genotypes belong to the same serotype. Genotypes 1 and 2 are typically waterborne, and genotypes 3 and 4 are typically transmitted from animals and humans. In general, the case fatality rate associated with HEV infection is 1% to 3%.12 In pregnancy, this rate increases to 5% to 25%.13,14 In Bangladesh, for example, hepatitis E is responsible for more than 1,000 deaths per year among pregnant women.15

Clinical presentation of HEV infection is a spectrum, with most symptomatic patients presenting with acute, self-limited hepatitis. Severe cases may be associated with pancreatitis, arthritis, aplastic anemia, and neurologic complications, such as seizures. Populations at risk for more severe cases include pregnant women, elderly men, and patients with pre‑ existing, chronic liver disease.

What this evidence means for practiceStandard sanitary precautions, such as clean drinking water, traditionally have been considered the mainstay of hepatitis E prevention. However, as the study authors indicate, recent severe outbreaks of HEV infection in Sudan and Uganda have occurred despite these measures. Thus, an effective vaccine that produces long-standing immunity has great potential for reducing morbidity and mortality in these countries. The present vaccine appears to be highly effective and safe. The principal unanswered question is the duration of immunity.

My patients are asking, "What is the best insect repellent to try to avoid Zika virus?"

With summer upon us we have received questions from colleagues about the best over-the-counter insect repellents to advise their pregnant patients to use.

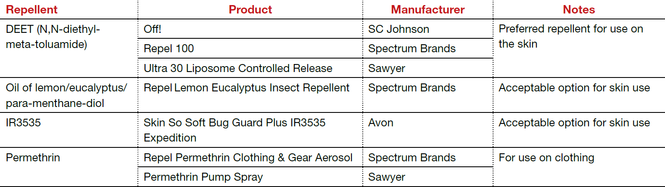

The preferred insect repellent for skin coverage is DEET (N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide) (TABLE). Oil of lemon/eucalyptus/para-menthane-diol and IR3535 are also acceptable repellents to use on the skin that are safe for use in pregnancy. In addition, instruct patients to spray permethrin on their clothing or to buy clothing (boots, pants, socks) that has been pretreated with permethrin.1,2

Anushka Chelliah, MD, and Patrick Duff, MD.

Abbreviation: OTC, over the counter.

Coming soon to OBG Management

Drs. Chelliah and Duff follow-up on their March 2016 examination of Zika virus infection with:

- Latest information on Zika virus-associated birth defects

- Ultrasonographic and radiologic evidence of abnormalities in the fetus and newborn exposed to Zika virus infection

- Link between Zika virus infection and serious neurologic complications in adults

- New recommendations for preventing sexual transmission of Zika virus infection

Dr. Chelliah is a Maternal Fetal Medicine-Fellow in the Division of Maternal Fetal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Florida College of Medicine, Gainesville.

Dr. Duff is Associate Dean for Student Affairs and Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology in the Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, University of Florida College of Medicine.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

References

- Peterson EE, Staples JE, Meaney-Delman D, et al. Interim guidelines for pregnant women during a Zika virus outbreak--United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(2):30-33.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Features: Avoid mosquito bites. https://www.cdc.gov/Features/stopmosquitoes/index.html. Updated March 18, 2016. Accessed May 10, 2016.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.