Vulvar pain syndromes: Causes and treatment of vestibulodynia

Although the origins of vestibulodynia are incompletely understood, this subset of vulvar pain is manageable and—good news—even curable in some cases

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Part 1: Making the correct diagnosis

(September 2011) - Part 2: A bounty of treatments—but not all of them are proven

(October 2011)

This three-part series concludes with a look at vestibulodynia—pain that is localized to the vulvar vestibule. Much is known about this disorder, compared with our knowledge base in the recent past, but much remains to be discovered. Among the questions explored by the panelists in this article is whether vestibulodynia and generalized vulvodynia are distinct entities—or different manifestations of the same process.

Other questions addressed here:

- Do oral contraceptives (OCs) contribute to vestibulodynia?

- What about herpes and genital warts? Are they causes of vestibular pain?

- Are some women more vulnerable to vestibulodynia than others?

- Is the disorder curable?

- Does vestibulectomy provide definitive treatment?

Part 1 of this series, which appeared in the September 2011 issue, focused on generalized vulvar pain and its causes, features, and diagnosis. Part 2, in the October issue, took as its subject the treatment of vulvar pain. Both are available in the archive at obgmanagement.com.

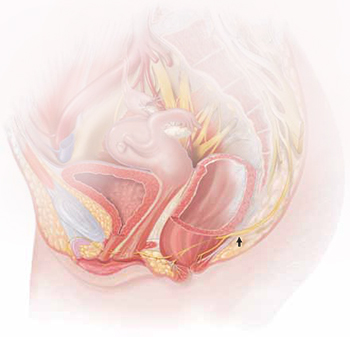

The lower vagina and vulva are richly supplied with peripheral nerves and are, therefore, sensitive to pain, particularly the region of the hymeneal ring. Although the pudendal nerve (arrow) courses through the area, it is an uncommon source of vulvar pain.

What do we know about the causes of vestibulodynia?

Dr. Lonky: What are the causes of provoked vestibulodynia (PVD), also known as vulvar vestibulitis syndrome? And what are the theories behind those causes?

Dr. Haefner: The specific cause is unknown. Most likely, there isn’t a single cause. Theories that have been proposed include abnormalities of embryologic development, infection, inflammation, genetic and immune factors, and nerve pathways.

Patients who have vestibulodynia may also have interstitial cystitis. It has been noted that tissues from the vestibule and bladder have a common embryologic origin and, therefore, are predisposed to similar pathologic responses when challenged.1,2

Candida albicans infection in patients who experience vestibular pain has also been studied. The exact association is difficult to determine because many patients report Candida infections without verified testing for yeast. Bazin and colleagues found a very weak association between infection and pain on the vestibule.3

Inflammation—the “itis” in vestibulitis—has been excluded from the recent International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) terminology because studies found no association between excised tissue and inflammation. Bohm-Starke and colleagues found low expression of the inflammatory markers cyclooxygenase 2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase in the vestibular mucosa of women who had localized vestibular pain, as well as in healthy women in the control group.4

Goetsch was one of the first researchers to explore a genetic association with localized vulvar pain.5 Fifteen percent of patients questioned over a 6-month period were found to have localized vestibular pain. Thirty-two percent had a female relative who had dyspareunia or tampon intolerance, raising the issue of a genetic predisposition. Another genetic connection was found in a study evaluating gene coding for interleukin 1-receptor antagonist.6–8

Krantz examined the nerve characteristics of the vulva and vagina.9 The region of the hymeneal ring was richly supplied with free nerve endings. No corpuscular endings of any form were observed. Only free nerve endings were observed in the fossa navicularis. A sparsity of nerve endings occurred in the vagina, as compared with the region of the fourchette, fossa navicularis, and hymeneal ring. More recent studies have analyzed the nerve factors, thermoreceptors, and nociceptors in women with vulvar pain.10,11

Dr. Edwards: I feel strongly that vestibulodynia and generalized vulvodynia are the same process. For example, tension headaches are supposed to be occipital, but some people experience tension headaches that are periorbital. Both are tension headaches despite the different locations. And almost all patients who experience any subset of vulvodynia have provoked vestibular pain. So the only thing that separates vestibulodynia from other patterns of vulvodynia is the option of vestibulectomy for therapy.

I don’t think that vulvodynia and vestibulodynia are “wastebasket” names for undiagnosable vulvar pain; rather, they are specific disease processes produced by pelvic floor dysfunction that predisposes a woman to neuropathic pain with a trigger or to a systemic pain syndrome that includes an abnormal pelvic floor.

Dr. Gunter: There are probably many causes of PVD, as Dr. Haefner suggested. There may be an ignition hypothesis, whereby some outside inflammatory trigger or trauma produces local neurogenic inflammation. However, given the prevalence of other pain disorders, there is probably also a need to have a lowered threshold for these changes to occur—basically, a vulnerable neurologic platform.

For some women, local neural hyperplasia is probably a factor. It is possible that there are different causes for primary and secondary vestibulodynia.