The Effects of a Multifaceted Intervention to Improve Care Transitions Within an Accountable Care Organization: Results of a Stepped-Wedge Cluster-Randomized Trial

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

BACKGROUND: Transitions from hospital to the ambulatory setting are high risk for patients in terms of adverse events, poor clinical outcomes, and readmission.

OBJECTIVES: To develop, implement, and refine a multifaceted care transitions intervention and evaluate its effects on postdischarge adverse events.

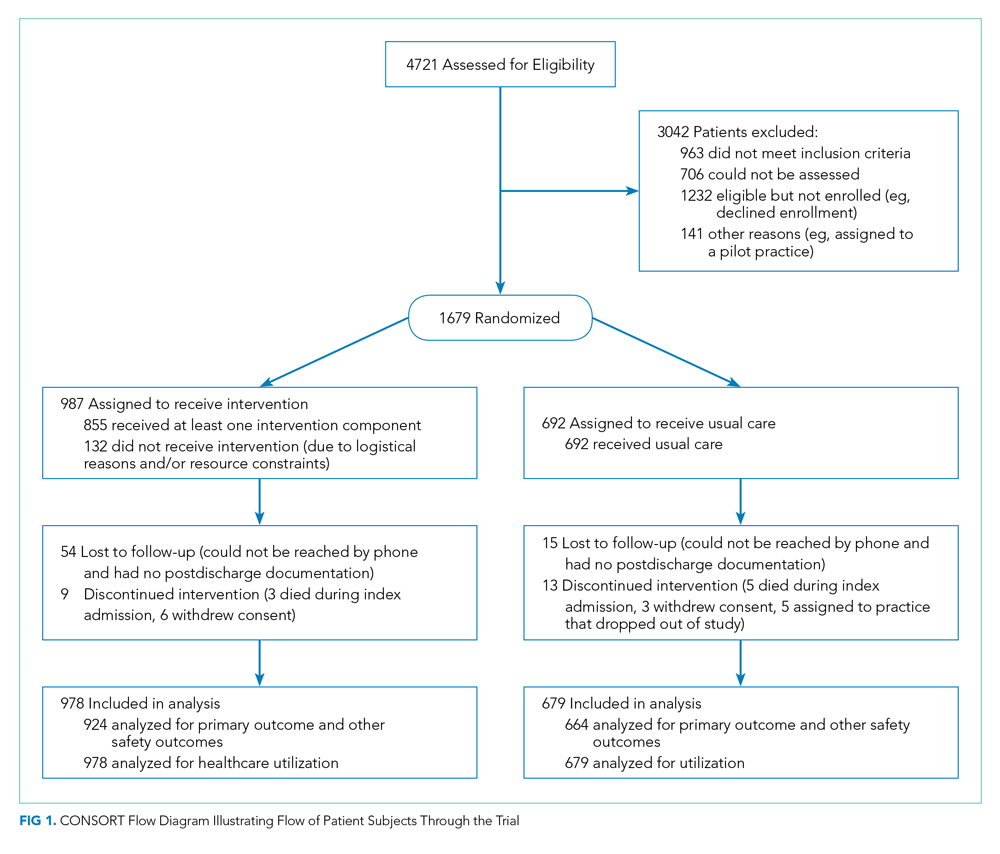

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS: Two-arm, single-blind (blinded outcomes assessor), stepped-wedge, cluster-randomized clinical trial. Participants were 1,679 adult patients who belonged to one of 17 primary care practices and were admitted to a medical or surgical service at either of two participating hospitals within a pioneer accountable care organization (ACO).

INTERVENTIONS: Multicomponent intervention in the 30 days following hospitalization, including: inpatient pharmacist-led medication reconciliation, coordination of care between an inpatient “discharge advocate” and a primary care “responsible outpatient clinician,” postdischarge phone calls, and postdischarge primary care visit.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES: The primary outcome was rate of postdischarge adverse events, as assessed by a 30-day postdischarge phone call and medical record review and adjudicated by two blinded physician reviewers. Secondary outcomes included preventable adverse events, new or worsening symptoms after discharge, and 30-day nonelective hospital readmission.

RESULTS: Among patients included in the study, 692 were assigned to usual care and 987 to the intervention. Patients in the intervention arm had a 45% relative reduction in postdischarge adverse events (18 vs 23 events per 100 patients; adjusted incidence rate ratio, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.35-0.84). Significant reductions were also seen in preventable adverse events and in new or worsening symptoms, but there was no difference in readmission rates.

CONCLUSION: A multifaceted intervention was associated with a significant reduction in postdischarge adverse events but no difference in 30-day readmission rates.

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

METHODS

This study was a two-arm, single-blind (blinded outcomes assessor), stepped-wedge, multisite cluster-randomized clinical trial (NCT02130570) approved by the institutional review board of Partners HealthCare.

Study Design and Randomization

The study employed a “stepped-wedge” design, which is a cluster-randomized study design in which an intervention is sequentially rolled out to different groups at different, prespecified, randomly determined times.9 Each cluster (in this case, each primary care practice) served as its own control, while still allowing for adjustment for temporal trends. Originally, 18 practices participated, but one withdrew due to the low number of patients enrolled in the study, leaving 17 clusters and 16 sequences; see Figure 1 of Appendix 1 for a full description of the sample size and timeline for each cluster. Practices were not aware of this timeline until after recruitment.

Study Setting and Participants

Conducted within a large Pioneer ACO in Boston and funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), the Partners-PCORI Transitions Study was designed as a “real-world” quality improvement project. Potential participants were adult patients who were admitted to medical and surgical services of two large academic hospitals (Hospital A and Hospital B) affiliated with an ACO, who were likely to be discharged back to the community, and whose PCP belonged to a primary care practice that was affiliated with the ACO, agreed to participate, and were designated PCMHs or on their way to being designated by meeting certain criteria: electronic health record, patient portal, team-based care, practice redesign, care management, and identification of high-risk patients. See Study Protocol (Appendix 2) for detailed patient and primary care practice inclusion criteria.

Patient Enrollment

Study staff screened participants from a daily automated list of patients admitted the day before, using medical records to determine eligibility, which was then confirmed by the patient’s nurse. Exclusion criteria included likely discharge to a location other than home, being in police custody, lack of a telephone, being homeless, previous enrollment in the study, and being unable to communicate in English or Spanish. Allocation to study arm was concealed until the patient or proxy provided informed written consent. The research assistant administered questionnaires to all study subjects to assess potential confounders and functional status 1 month prior to admission (

Intervention

The intervention was based on a conceptual model of an ideal discharge11 that we developed based on work by Naylor et al,12 work by Coleman and Berenson,3 best practices in medication reconciliation and information transfer according to our own research,13-15 the best examples of interventions to improve the discharge process,12,16,17 and a systematic review of discharge interventions.18 Some of the factors necessary for an ideal care transition include complete, organized, and timely documentation of the patient’s hospital course and postdischarge plan; effective discharge planning; coordination of care among the patient’s providers; methods to ensure medication safety; advanced care planning in appropriate patients; and education and “coaching” of patients and their caregivers so they learn how to manage their conditions. The final multifaceted intervention addressed each component of the ideal discharge and included inpatient and outpatient components (Table 1 and Table 1 of Appendix 1).