Examining the “Repletion Reflex”: The Association between Serum Potassium and Outcomes in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure

BACKGROUND: In patients hospitalized with heart failure (HF) exacerbations, physicians routinely supplement potassium to maintain levels ≥4.0 mEq/L. The evidence basis for this practice is relatively weak. We aimed to evaluate the association between serum potassium levels and outcomes in patients hospitalized with HF.

METHODS: We identified patients admitted with acute HF exacerbations to hospitals that contributed to an electronic health record-derived dataset. In a subset of patients with normal admission serum potassium (3.5-5.0 mEq/L), we averaged serum potassium values during a 72-hour exposure window and categorized as follows: <4.0 mEq/L (low normal), 4.0-4.5 mEq/L (medium normal), and >4.5 mEq/L (high normal). We created multivariable models examining associations between these categories and outcomes.

RESULTS: We included 4,995 patients: 2,080 (41.6%), 2,326 (46.6%), and 589 (11.8%) in the <4.0, 4.0-4.5, and >4.5 mEq/L cohorts, respectively. After adjustment for demographics, comorbidities, and presenting severity, we observed no difference in outcomes between the low and medium normal groups. Compared to patients with levels <4.0 mEq/L, patients with a potassium level of >4.5 mEq/L had a longer length of stay (median of 0.6 days; 95% CI: 0.1 to 1.0) but did not have statistically significant increases in mortality (OR [odds ratio] = 1.51; 95% CI: 0.97 to 2.36) or transfers to the intensive care unit (OR = 1.78; 95% CI: 0.98 to 3.26).

CONCLUSIONS: Inpatients with heart failure who had mean serum potassium levels of <4.0 showed similar outcomes to those with mean serum potassium values of 4.0-4.5. Compared with mean serum potassium level of <4.0, mean serum levels of >4.5 may be associated with increased risk of poor outcomes.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

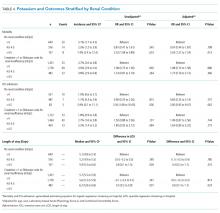

When stratifying our results by the presence or absence of acute or chronic renal insufficiency, we continued to observe no increased risk of any outcome in the 4.0-4.5 mEq/L compared with the <4.0 mEq/L groups across all strata (Table 4). Interestingly, even after adjustment, we did find that most of the increased risk of mortality and ICU admission in the >4.5 versus <4.0 mEq/L groups was among those without renal insufficiency (mortality OR = 3.03; ICU admission OR = 3.00) and was not statistically significant in those with renal insufficiency (mortality OR = 1.27; ICU admission OR = 1.63). Adjusted LOS estimates remained relatively similar in this stratified analysis.

DISCUSSION

The best approach to mild serum potassium value abnormalities in patients hospitalized with HF remains unclear. Many physicians reflexively replete potassium to ensure all patients maintain a serum value of >4.0 mEq/L.15 Yet, in this large observational study of patients hospitalized with an acute HF exacerbation, we found little evidence of association between serum potassium <4.0 mEq/L and negative outcomes.

Compared with those with mean potassium values <4.0 mEq/L (in unadjusted models), there was an association between potassium values of >4.5 mEq/L and increased risk of mortality and ICU transfer. This association was attenuated after adjustment, suggesting that factors beyond potassium values influenced the observed relationship. These findings seem to suggest that unobserved differences in the >4.5 mEq/L group (there were observed differences in this group, eg, greater presenting severity and higher comorbidity scores, suggesting that there were also unobserved differences), and not average potassium value, were the reasons for the observed differences in outcomes. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that potassium >4.5 mEq/L has some associated increased risk compared with mean potassium values of <4.0 mEq/L for patients hospitalized with acute decompensated HF.

Patients in our study routinely received exogenous potassium: more than 70% of patients received repletion at least once, although it is notable that the majority of patients in the 4.0-4.5 and >4.5 mEq/L groups did not receive repletion. Despite this practice, the data supporting this approach to potassium management for patients hospitalized with HF remain mixed. A serum potassium decline of >15% during an acute HF hospital stay has been reported as a predictor of all-cause mortality after controlling for disease severity and associated comorbidities, including renal function.25 However, this study was focused on decline in admission potassium rather than an absolute cut-off (eg, >4.0 mEq/L). Additionally, potassium levels <3.9 mEq/L were associated with increased mortality in patients with acute HF following a myocardial infarction, but this study was not focused on patients with HF.26 Most of the prior literature in patients with HF was conducted in patients in outpatient settings and examined patients who were not experiencing acute exacerbations. MacDonald and Struthers advocate that patients with HF have their potassium maintained above 4.0 mEq/L but did not specify whether this included patients with acute HF exacerbations.10 Additionally, many studies evaluating potassium repletion were conducted before widespread availability of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or potassium-sparing diuretics, including spironolactone. Prior work has consistently reported that hyperkalemia, defined as serum potassium >4.5 mEq/L, is associated with mortality in patients with acute HF over the course of hospitalization (which aligned with the results from our sensitivity analysis), but concurrent medication regimens and underlying impaired renal function likely accounted for most of this association.17 The picture is further complicated as patients with acute HF presenting with hypokalemia may be at risk for subsequent hyperkalemia, and potassium repletion can stimulate aldosterone secretion, potentially exacerbating underlying HF.27,28

These data are observational and are unlikely to change practice. However, daily potassium repletion represents a huge cost in time, money, and effort to the health system. Furthermore, the greatest burden occurs for the patients, who have labs drawn and values checked routinely and potassium administered orally or parenterally. While future randomized clinical trials (RCTs) would best examine the benefits of repletion, future pragmatic trials could attempt to disentangle the associated risks and benefits of potassium repletion in the absence of RCTs. Additionally, such studies could better take into account the role of concurrent medication use (like ACEs or angiotensin II receptor blockers), as well as assess the role of chronic renal insufficiency, acute kidney injury, and magnesium levels.29

This study has limitations. Its retrospective design leads to unmeasured confounding; however, we adjusted for multiple variables (including LAPS-2), which reflect the severity of disease at admission and underlying kidney function at presentation, as well as other comorbid conditions. In addition, data from the cohort only extend to 2012, so more recent changes in practice may not be completely reflected. The nature of the data did not allow us to directly investigate the relationship between serum potassium and arrhythmias, although ICU transfer and mortality were used as surrogates.

In conclusion, the benefit of a serum potassium level >4.0 mEq/L in patients admitted with HF remains unclear. We did not observe that mean potassium values <4.0 mEq/L were associated with worse outcomes, and, more concerning, there may be some risk for patients with mean values >4.5 mEq/L.