Association between Inpatient Delirium and Hospital Readmission in Patients ≥ 65 Years of Age: A Retrospective Cohort Study

BACKGROUND: Delirium affects more than seven million hospitalized adults in the United States annually. However, its impact on postdischarge healthcare utilization remains unclear.

OBJECTIVE: To determine the association between delirium and 30-day hospital readmission.

DESIGN: A retrospective cohort study.

SETTING: A general community medical and surgical hospital.

PATIENTS: All adults who were at least 65 years old, without a history of delirium or alcohol-related delirium, and were hospitalized from September 2010 to March 2015.

MEASUREMENTS: The patients deemed at risk for or displaying symptoms of delirium were screened by nurses using the Confusion Assessment Method with a follow-up by a staff psychiatrist for a subset of screen-positive patients. Patients with delirium confirmed by a staff psychiatrist were compared with those without delirium. The primary outcome was the 30-day readmission rate. The secondary outcomes included emergency department (ED) visits 30 days postdischarge, mortality during hospitalization and 30 days postdischarge, and discharge location.

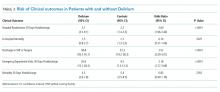

RESULTS: The cohort included 718 delirious patients and 7,927 nondelirious patients. Using an unweighted multivariable logistic regression, delirium was determined to be significantly associated with the increased odds of readmission within 30 days of discharge (odds ratio (OR): 2.60; 95% CI, 1.96-3.44; P < .0001). Delirium was also significantly (P < .0001) associated with ED visits within 30 days postdischarge (OR: 2.18; 95% CI: 1.77-2.69) and discharge to a facility (OR: 2.52; 95% CI: 2.09-3.01).

CONCLUSIONS: Delirium is a significant predictor of hospital readmission, ED visits, and discharge to a location other than home. Delirious patients should be targeted to reduce postdischarge healthcare utilization.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Primary Outcome

Delirium during admission was significantly associated with hospital readmission within 30 days of discharge (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 2.60, 95% CI: 1.96–3.44; P < .0001; Table 3).

Secondary Outcomes

Delirium during admission was significantly (P < .0001; Table 3) associated with an ED visit within 30 days of discharge (OR: 2.18; 95% CI: 1.77–2.69) and discharge to a skilled nursing facility or hospice rather than home (OR: 2.52; 95% CI: 2.09–3.01). Delirium was not associated (P > .1) with death during hospitalization nor death 30 days following discharge.

As the delirious patients were much more likely to be discharged to a skilled nursing facility than nondelirious patients, we tested whether discharge disposition influenced readmission rates and ED visits between delirious and nondelirious patients in an unadjusted univariate analysis. The association between delirium and readmission and ED utilization was present regardless of disposition. Among patients discharged to skilled nursing, readmission rates were 4.76% and 13.38% (P < .001), and ED visit rates were 12.29% and 23.24% (P < .001) for nondelirious and delirious patients, respectively. Among patients discharged home, readmission rates were 4.96% and 14.37% (P < .001), and ED visit rates were 11.93% and 29.04% (P < .001) for nondelirious and delirious patients, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In this study of patients in a community hospital in Northern California, we observed a significant association between inpatient delirium and risk of hospital readmission within 30 days of discharge. We also demonstrated increased skilled nursing facility placement and ED utilization after discharge among hospitalized patients with delirium compared with those without. Patients with delirium in this study were diagnosed by a psychiatrist—a gold standard30—and the study was conducted in a health system database with near comprehensive ascertainment of readmissions. These results suggest that patients with delirium are particularly vulnerable in the posthospitalization period and are a key group to focusing on reducing readmission rates and postdischarge healthcare utilization.

Identifying the risk factors for hospital readmission is important for the benefit of both the patient and the hospital. In an analysis of Medicare claims data from 2003 to 2004, 19.6% of beneficiaries were readmitted within 30 days of discharge.31 There is a national effort to reduce unplanned hospital readmissions for both patient safety as hospitals with high readmission rates face penalties from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.22,23 Why delirium is associated with readmission remains unclear. Delirium may precipitate aspiration events, reduce oral intake which complicates medication administration and nutrition, or reduced mobility, leading to pulmonary emboli and skin breakdown, any of which could lead to readmission.32 Delirium may also accelerate the progression of cognitive decline and overall loss of functional independence.20 Delirious patients can be difficult to care for at home, and persistent delirium may lead to returns to the ED and readmission. Strategies to reduce readmissions associated with delirium may need to focus on both prevention of hospital-acquired delirium and targeted caregiver and patient support after discharge.

Hospital readmission and ED visits are not mutually exclusive experiences. In the United States, the majority of patients admitted to the hospital are admitted through the ED.33 Thus, most of the readmissions in this cohort were also likely counted as 30-day ED visits. However, as ED utilization occurs regardless of whether a patient is discharged or admitted from the ED, we reported all ED visits in this analysis, similar to other studies.34 More delirium patients returned to the ED 30 days postdischarge than were ultimately readmitted to the hospital, and delirious patients were more likely to visit the ED or be readmitted than nondelirious patients. These observations point toward the first 30 days after discharge as a crucial period for these patients.

Our study features several strengths. To our knowledge, this study is one of the largest investigations of inpatients with delirium. One distinguishing feature was that all cases of delirium in this study were diagnosed by a psychiatrist, which is considered a gold standard. Many studies rely solely on brief nursing-administered surveys for delirium diagnosis. Using Kaiser Permanente data allowed for more complete follow-up of patients, including vital status. Kaiser Permanente is both a medical system and an insurer, resulting in acquisition of detailed health information from all hospitalizations where Kaiser Permanente insurance was used for each patient. Therefore, patients were only lost to follow-up following discharge in the event of a membership lapse; these patients were excluded from analysis. The obtained data are also more generalizable than those of other studies examining readmission rates in delirious patients as the hospital where these data were collected is a 116-bed general community medical and surgical hospital. Thus, the patients enrolled in this study covered multiple hospital services with a variety of admission diagnoses. This condition contrasts with much of the existing literature on inpatient delirium; these studies mostly center on specific medical conditions or surgeries and are often conducted at academic medical centers. At the same time, Kaiser Permanente is a unique health maintenance organization focused on preventive care, and readmission rates are possibly lower than elsewhere given the universal access to primary care for Kaiser Permanente members. Our results may not generalize to patients hospitalized in other health systems.

The diagnosis of delirium is a clinical diagnosis without biomarkers or radiographic markers and is also underdiagnosed and poorly coded.32 For these reasons, delirium can be challenging to study in large administrative databases or data derived from electronic medical records. We addressed this limitation by classifying the delirium patients only when they had been diagnosed by a staff psychiatrist. However, not all patients who screened positive with the CAM were evaluated by the staff psychiatrist during the study period. Thus, several CAM-positive patients who were not evaluated by psychiatry were included in the control population. This situation may cause bias toward identification of more severe cases of delirium. Although the physicians were encouraged to consult the psychiatry department for any patients who screened positive for delirium with the CAM, the psychiatrist may not have been involved if patients were managed without consultation. These patients may have exhibited less severe delirium or hypoactive delirium. In addition, the CAM fails to detect all delirious patients; interrater variability may occur with CAM administration, and non-English speaking patients are more likely to be excluded.35 These situations are another possible way for our control population to include some delirious patients and those patients with less severe or hypoactive subtypes. While this might bias toward the null hypothesis, it is also possible our results only indicate an association between more clinically apparent delirium and readmission. A major limitation of this study is that we were unable to quantify the number of cohort patients screened with the CAM or the results of screening, thus limiting our ability to quantify the impact of potential biases introduced by the screening program.

This study may have underestimated readmission rates. We defined readmissions as all hospitalizations at any Kaiser Permanente facility, or to an alternate facility where Kaiser Permanente insurance was used, within 30 days of discharge. We excluded the day of discharge or the following calendar day to avoid mischaracterizing transfers from the index hospital to another Kaiser Permanente facility as readmissions. This step was conducted to avoid biasing our comparison, as delirious patients are less frequently discharged home than nondelirious patients. Therefore, while the relative odds of readmission between delirious and nondelirious patients reported in this study should be generalizable to other community hospitals, the absolute readmission rates reported here may not be comparable to those reported in other studies.

Delirium may represent a marker of more severe illness or medical complications accrued during the hospitalization, which could lead to the associations observed in this study due to confounding.32 Patients with delirium are more likely to be admitted emergently, admitted to the ICU, and feature higher acuity conditions than patients without delirium. We attempted to mitigate this possibility by using a multivariable model to control for variables related to illness severity, including the Charlson comorbidity index, HCUP diagnostic categories, and ICU admission. Despite including HCUP diagnostic categories in our model, we were unable to capture the contribution of certain diseases with finer granularity, such as preexistent dementia, which may also affect clinical outcomes.36 Similarly, although we incorporated markers of illness severity into our model, we were unable to adjust for baseline functional status or frailty, which were not reliably recorded in the electronic medical record but are potential confounders when investigating clinical outcomes including hospital readmission.

We also lacked information regarding the duration of delirium in our cohort. Therefore, we were unable to test whether longer episodes of delirium were more predictive of readmission than shorter episodes.