Association between Inpatient Delirium and Hospital Readmission in Patients ≥ 65 Years of Age: A Retrospective Cohort Study

BACKGROUND: Delirium affects more than seven million hospitalized adults in the United States annually. However, its impact on postdischarge healthcare utilization remains unclear.

OBJECTIVE: To determine the association between delirium and 30-day hospital readmission.

DESIGN: A retrospective cohort study.

SETTING: A general community medical and surgical hospital.

PATIENTS: All adults who were at least 65 years old, without a history of delirium or alcohol-related delirium, and were hospitalized from September 2010 to March 2015.

MEASUREMENTS: The patients deemed at risk for or displaying symptoms of delirium were screened by nurses using the Confusion Assessment Method with a follow-up by a staff psychiatrist for a subset of screen-positive patients. Patients with delirium confirmed by a staff psychiatrist were compared with those without delirium. The primary outcome was the 30-day readmission rate. The secondary outcomes included emergency department (ED) visits 30 days postdischarge, mortality during hospitalization and 30 days postdischarge, and discharge location.

RESULTS: The cohort included 718 delirious patients and 7,927 nondelirious patients. Using an unweighted multivariable logistic regression, delirium was determined to be significantly associated with the increased odds of readmission within 30 days of discharge (odds ratio (OR): 2.60; 95% CI, 1.96-3.44; P < .0001). Delirium was also significantly (P < .0001) associated with ED visits within 30 days postdischarge (OR: 2.18; 95% CI: 1.77-2.69) and discharge to a facility (OR: 2.52; 95% CI: 2.09-3.01).

CONCLUSIONS: Delirium is a significant predictor of hospital readmission, ED visits, and discharge to a location other than home. Delirious patients should be targeted to reduce postdischarge healthcare utilization.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

The development of delirium is associated with several negative outcomes during the hospital stay. Delirium is an independent predictor of prolonged hospital stay,7,9,12,13 prolonged mechanical ventilation,14 and mortality during admission.14,15 Inpatient delirium is associated with functional decline at discharge, leading to a new nursing home placement.16-19 Preexisting dementia is exacerbated by inpatient delirium, and a new diagnosis of cognitive impairment20 or dementia becomes more common after an episode of delirium.21

These data suggest that people diagnosed with delirium may be particularly vulnerable in the posthospitalization period. Hospitals with high rates of unplanned readmissions face penalties from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.22,23 However, few investigations have focused on postdischarge healthcare utilization, such as readmission rates and ED visits. Studies that address this topic are limited to postoperative patient populations.24

Using a cohort of hospitalized patients, we examined whether those diagnosed with delirium experienced worse outcomes compared with patients with no such condition. We hypothesized that the patients diagnosed with delirium during hospitalization would experience more readmissions and ED visits within 30 days of discharge compared with those without delirium.

METHODS

Study Design

This single-center retrospective cohort study took place at the Kaiser Permanente San Rafael Medical Center (KP-SRF), a 116-bed general community medical and surgical hospital located in Northern California, from September 6, 2010 to March 31, 2015. The Kaiser Permanente Northern California institutional review board, in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of the Helsinki and International Conference on Harmonization Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice (CN-15-2491-H), approved this study.

Participants and Eligibility Criteria

This study included Kaiser Permanente members at least 65 years old who were hospitalized at KP-SRF from September 2010 to March 2015. Patient data were obtained from the electronic medical records. Patients with delirium were identified from a delirium registry; all other patients served as controls.

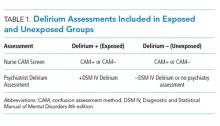

Starting on September 6, 2010, a hospital-wide program was initiated to screen hospitalized medical and surgical patients using the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM).25 As part of this program, nurses completed a four-hour training on delirium; the program included delirium identification and CAM administration. Patients deemed at risk for delirium by their nurse or displaying symptoms of delirium (fluctuation in attention or awareness, disorientation, restlessness, agitation, and psychomotor slowing) were screened by nurses one to two times within a 24-hour period. Physicians were notified by the nurse if their patient screened positive. Nurses were prohibited from performing CAMs in languages that they were not fluent in, thus resulting in screening of primarily English-speaking patients. Psychiatry was consulted at the discretion of the primary team physician to assist with diagnosis and management of delirium. As psychiatry consultation was left up to the discretion of the primary team physician, not all CAM-positive patients were evaluated. The psychiatrists conducted no routine evaluation on the CAM-negative patients unless requested by the primary team physician. The psychiatrist confirmed the delirium diagnosis with a clinical interview and assessment. The patients confirmed with delirium at any point during their hospitalization were prospectively added to a delirium registry. The patients assessed by the psychiatrist as not delirious were excluded from the registry. Only those patients added to the delirium registry during the study period were classified as delirious for this study. All other patients were included as controls. The presence of the nursing screening program using the CAM enriched the cohort, but a positive CAM was unnecessary nor was it sufficient for inclusion in the delirium group (Table 1).

To eliminate the influence of previous delirium episodes on readmission, the subjects were excluded if they reported a prior diagnosis of delirium in 2006 or later, which was the year the electronic medical record was initiated. This diagnosis was determined retrospectively using the following ICD-9 codes: 290.11, 290.3, 290.41, 292.0, 292.81, 292.89, 293.0, 293.0E, 293.0F, 293.1, 293.89, 294.10, 294.21, 304.00, 304.90, 305.50, 331.0, 437.0, 780.09, V11.8, and V15.89.26 Subjects were also excluded if they were ever diagnosed with alcohol-related delirium, as defined by ICD-9 codes 291, 303.9, and 305. Subjects were excluded from the primary analysis if Kaiser Permanente membership lapsed to any degree within 30 days of discharge. Patients who died in the hospital were not excluded; however, the analyses of postdischarge outcomes were conducted on the subpopulation of study subjects who were discharged alive.

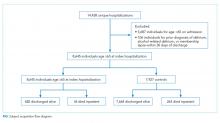

For subjects with multiple entries in the delirium registry, the earliest hospitalization during the study period in which a delirium diagnosis was recorded was selected. For eligible patients without a diagnosis of delirium, a single hospitalization was selected randomly from the individual patients during the time period. The analysis database included only one hospitalization for each subject. The flowchart of patient selection is outlined in the Figure.