Reducing Unnecessary Treatment of Asymptomatic Elevated Blood Pressure with Intravenous Medications on the General Internal Medicine Wards: A Quality Improvement Initiative

BACKGROUND: Asymptomatic elevated blood pressure (BP) is common in the hospital. There is no evidence supporting the use of intravenous (IV) antihypertensives in this setting.

OBJECTIVE: To determine the prevalence and effects of treating asymptomatic elevated BP with IV antihypertensives and to investigate the efficacy of a quality improvement (QI) initiative aimed at reducing utilization of these medications.

DESIGN: Retrospective cohort study.

SETTING: Urban academic hospital. PATIENTS: Patients admitted to the general medicine service, including the intensive care unit (ICU), with ≥1 episode of asymptomatic elevated BP (>160/90 mm Hg) during hospitalization.

INTERVENTION: A two-tiered, QI initiative.

MEASUREMENTS: The primary outcome was the monthly proportion of patients with asymptomatic elevated BP treated with IV labetalol or hydralazine. We also analyzed median BP and rates of balancing outcomes (ICU transfers, rapid responses, cardiopulmonary arrests).

RESULTS: We identified 2,306 patients with ≥1 episode of asymptomatic elevated BP during the 10-month preintervention period, of which 251 (11%) received IV antihypertensives. In the four-month postintervention period, 70 of 934 (7%) were treated. The odds of being treated were 38% lower in the postintervention period after adjustment for baseline characteristics, including length of stay and illness severity (OR = 0.62; 95% CI 0.47-0.83; P = .001). Median SBP was similar between pre- and postintervention (167 vs 168 mm Hg; P = .78), as were the adjusted proportions of balancing outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS: Hospitalized patients with asymptomatic elevated BP are commonly treated with IV antihypertensives, despite the lack of evidence. A QI initiative was successful at reducing utilization of these medications.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Of the 934 patients with ≥1 episode of asymptomatic elevated BP, 70 (7%) were treated with IV antihypertensive medications, with a total of 196 doses administered. The proportion of patients treated per month during the postintervention period ranged from 6% to 8%, which was the lowest of the entire study period and below the baseline average of 10% (Figure).

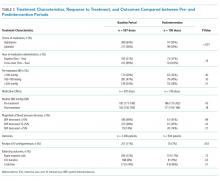

In a patient-level logistic regression pre-post analysis adjusting for age, sex, race, ethnicity, primary language, insurance status, preexisting HTN, length of stay, and APR-DRG weight, patients admitted to the general medicine service during the postintervention period had 38% lower odds of receiving IV antihypertensive medications than those admitted during the baseline period (OR = 0.62; 95% CI 0.47-0.83; P = .001). In this adjusted model, the following factors were independently associated with increased odds of receiving treatment: APR-DRG weight (OR 1.13; 95% CI 1.07-1.20; P < .001), Black race (OR 1.81; 95% CI 1.29-2.53; P = .001), length of stay (OR 1.02; 95% CI 1.01-1.03; P < .001), and preexisting HTN (OR 4.25; 95% CI 2.75-6.56; P < .001). Older age was associated with lower odds of treatment (Table 2).

Among patients who received treatment, there were no differences between pre- and postintervention periods in the proportion of pretreatment SBP <180 mm Hg (29% vs 32%; P = .40), 180-199 mm Hg (47% vs 40%; P = .10), or >200 mm Hg (25% vs 28%; P = .31; Table 3).

Population-level median SBP was similar between pre- and postintervention periods (167 mm Hg vs 168 mm Hg, P = .78), as were unadjusted rates of rapid response calls, ICU transfers, and code blues (Table 3). After adjustment for baseline characteristics and illness severity at the patient level, the odds of rapid response calls (OR 0.84; 95% CI 0.65-1.10; P = .21) and ICU transfers (OR 1.01; 95% CI 0.75-1.38; P = .93) did not differ between pre- and postintervention periods. A regression model was not fit for cardiopulmonary arrests due to the low absolute number of events.

CONCLUSIONS

Our results suggest that treatment of asymptomatic elevated BP using IV antihypertensive medications is common practice at our institution. We found that treatment is often initiated for only modestly elevated BPs and that the clinical response to these medications is highly variable. In the baseline period, one in seven patients experienced a decrement in BP >25% following treatment, which could potentially cause harm.11 There is no evidence, neither are there any consensus guidelines, to support the rapid reduction of BP among asymptomatic patients, making this a potential valuable opportunity for reducing unnecessary treatment, minimizing waste, and avoiding harm.

While there are a few previously published studies with similar results, we add to the existing literature by studying a larger population of more than 3,000 total patients, which was uniquely multiracial, including a high proportion of non-English speakers. Furthermore, our cohort included patients in the ICU, which is reflected in the higher-than-average APR-DRG weights. Despite being critically ill, these patients arguably still do not warrant aggressive treatment of elevated BP when asymptomatic. By excluding symptomatic BP elevations using surrogate markers for end-organ damage in addition to discharge diagnosis codes indicative of conditions in which tight BP control may be warranted, we were able to study a more critically ill patient population. We were also able to describe which baseline patient characteristics convey higher adjusted odds of receiving treatment, such as preexisting HTN, younger age, illness severity, and black race.

Perhaps most significantly, our study is the first to demonstrate an effective QI intervention aimed at reducing unnecessary utilization of IV antihypertensives. We found that this can feasibly be accomplished through a combination of educational efforts and systems changes, which could easily be replicated at other institutions. While the absolute reduction in the number of patients receiving treatment was modest, if these findings were to be widely accepted and resulted in a wide-spread change in culture, there would be a potential for greater impact.

Despite the reduction in the proportion of patients receiving IV antihypertensive medications, we found no change in the median SBP compared with the baseline period, which seems to support that the intervention was well tolerated. We also found no difference in the number of ICU transfers, rapid response calls, and cardiopulmonary arrests between groups. While these findings are both reassuring, it is impossible to draw definitive conclusions about safety given the small absolute number of patients having received treatment in each group. Fortunately, current guidelines and literature support the safety of such an intervention, as there is no existing evidence to suggest that failing to rapidly lower BP among asymptomatic patients is potentially harmful.11

There are several limitations to our study. First, by utilizing a large electronic dataset, the quality of our analyses was reliant on the accuracy of the recorded EHR data. Second, in the absence of a controlled trial or control group, we cannot say definitively that our QI initiative was the direct cause of the improved rates of IV antihypertensive utilization, though the effect did persist after adjusting for baseline characteristics in patient-level models. Third, our follow-up period was relatively short, with fewer than half as many patients as in the preintervention period. This is an important limitation, since the impact of QI interventions often diminishes over time. We plan to continually monitor IV antihypertensive use, feed those data back to our group, and revitalize educational efforts should rates begin to rise. Fourth, we were unable to directly measure which patients had true end-organ injury and instead used orders placed around the time of medication administration as a surrogate marker. While this is an imperfect measure, we feel that in cases where a provider was concerned enough to even test for end-organ injury, the use of IV antihypertensives was likely justified and was therefore appropriately excluded from the analysis. Lastly, we were limited in our ability to describe associations with true clinical outcomes, such as stroke or myocardial infarction, which could theoretically be propagated by either the use or the avoidance of IV antihypertensive medications. Fortunately, based on clinical guidelines and existing evidence, there is no reason to believe that reducing IV antihypertensive use would result in increased rates of these outcomes.

Our study reaffirms the fact that overutilization of IV antihypertensive medications among asymptomatic hospitalized patients is pervasive across hospital systems. This represents a potential target for a concerted change in culture, which we have demonstrated can be feasibly accomplished through education and systems changes.