Reducing Unnecessary Treatment of Asymptomatic Elevated Blood Pressure with Intravenous Medications on the General Internal Medicine Wards: A Quality Improvement Initiative

BACKGROUND: Asymptomatic elevated blood pressure (BP) is common in the hospital. There is no evidence supporting the use of intravenous (IV) antihypertensives in this setting.

OBJECTIVE: To determine the prevalence and effects of treating asymptomatic elevated BP with IV antihypertensives and to investigate the efficacy of a quality improvement (QI) initiative aimed at reducing utilization of these medications.

DESIGN: Retrospective cohort study.

SETTING: Urban academic hospital. PATIENTS: Patients admitted to the general medicine service, including the intensive care unit (ICU), with ≥1 episode of asymptomatic elevated BP (>160/90 mm Hg) during hospitalization.

INTERVENTION: A two-tiered, QI initiative.

MEASUREMENTS: The primary outcome was the monthly proportion of patients with asymptomatic elevated BP treated with IV labetalol or hydralazine. We also analyzed median BP and rates of balancing outcomes (ICU transfers, rapid responses, cardiopulmonary arrests).

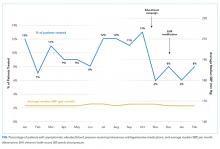

RESULTS: We identified 2,306 patients with ≥1 episode of asymptomatic elevated BP during the 10-month preintervention period, of which 251 (11%) received IV antihypertensives. In the four-month postintervention period, 70 of 934 (7%) were treated. The odds of being treated were 38% lower in the postintervention period after adjustment for baseline characteristics, including length of stay and illness severity (OR = 0.62; 95% CI 0.47-0.83; P = .001). Median SBP was similar between pre- and postintervention (167 vs 168 mm Hg; P = .78), as were the adjusted proportions of balancing outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS: Hospitalized patients with asymptomatic elevated BP are commonly treated with IV antihypertensives, despite the lack of evidence. A QI initiative was successful at reducing utilization of these medications.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

We further identified all instances in which either IV labetalol or hydralazine were administered to these patients. These two agents were chosen because they are the only IV antihypertensives used commonly at our institution for the treatment of asymptomatic elevated BP among internal medicine patients. Only those orders placed by a general medicine provider or reconciled by a general medicine provider upon transfer from another service were included. For each medication administration timestamp, we collected vital signs before and after the administration, along with the ordering provider and the clinical indication that was documented in the electronic order. To determine if a medication was administered with concern for end-organ injury, we also extracted orders that could serve as a proxy for the provider’s clinical assessment—namely electrocardiograms, serum troponins, chest x-rays, and computerized tomography scans of the head—which were placed in the one hour preceding or 15 minutes following administration of an IV antihypertensive medication.

To assess for comorbid conditions, including a preexisting diagnosis of HTN, we collected International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9/10 diagnosis codes. Further, we also extracted All Patient Refined Diagnosis-Related Group (APR-DRG) weights, which are a standardized measure of illness severity based on relative resource consumption during hospitalization.16,17

Patients were categorized as having either “symptomatic” or “asymptomatic” elevated BP. We defined symptomatic elevated BP as having received treatment with an IV medication with provider concern for end-organ injury, as defined above. We further identified all patients in which tight BP control may be clinically indicated on the basis of the presence of any of the following ICD-9/10 diagnosis codes at the time of hospital discharge: myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, subdural hematoma, aortic dissection, hypertensive emergency, or hypertensive encephalopathy. All patients with symptomatic elevated BP or any of the above ICD-9/10 diagnoses were excluded from the analysis, since administration of IV antihypertensive medications would plausibly be warranted in these clinical scenarios.

The encounter numbers from the dataset were used to link to patient demographic data, which included age, sex, race, ethnicity, primary language, and insurance status. Finally, we identified all instances of rapid response calls, ICU transfers, and code blues (cardiopulmonary arrests) for each patient in the dataset.

Blood Pressure Measurements

BP data were collected from invasive BP (IBP) monitoring devices and noninvasive BP cuffs. For patients with BP measurements recorded concomitantly from both IBP (ie, arterial lines) in addition to noninvasive BP cuffs, the arterial line reading was favored. All systolic BP (SBP) readings >240 mm Hg from arterial lines were excluded, as this has previously been described as the upper physiologic limit for IBP readings.18

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome for the study was the proportion of patients treated with IV antihypertensive medications (labetalol or hydralazine). Using aggregate data, we calculated the number of patients who were treated at least once with an IV antihypertensive in a given month (numerator), divided by the number of patients with ≥1 episode of asymptomatic elevated BP that month (denominator). The denominator was considered to be the population of patients “at risk” of being treated with IV antihypertensive medications. For patients with multiple admissions during the study period, each admission was considered separately. These results are displayed in the upper portion of the run chart (Figure).