Readmissions after Pediatric Hospitalization for Suicide Ideation and Suicide Attempt

OBJECTIVE: To inform resource allocation toward a continuum of care for youth at risk of suicide, we examined unplanned 30-day readmissions after pediatric hospitalization for either suicide ideation (SI) or suicide attempt (SA).

METHODS: We conducted a retrospective cohort study of a nationally representative sample of 133,516 hospitalizations for SI or SA among 6- to 17-year-olds to determine prevalence, risk factors, and characteristics of 30-day readmissions using the 2013 and 2014 Nationwide Readmissions Dataset (NRD). Risk factors for readmission were modeled using logistic regression.

RESULTS: We identified 95,354 hospitalizations for SI and 38,162 hospitalizations for SA. Readmission rates within 30 days were 8.5% for SI and SA hospitalizations. Among 30-day readmissions, more than one-third (34.1%) occurred within 7 days. Among patients with any 30-day readmission, 11% had more than one readmission within 30 days. The strongest risk factors for readmission were SI or SA hospitalization in the 30 days preceding the index SI/SA hospitalization (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]: 3.14, 95% CI: 2.73-3.61) and hospitalization for other indications in the previous 30 days (AOR: 3.18, 95% CI: 2.67-3.78). Among readmissions, 94.5% were for a psychiatric condition and 63.4% had a diagnosis of SI or SA.

CONCLUSIONS: Quality improvement interventions to reduce unplanned 30-day readmissions among children hospitalized for SI or SA should focus on children with a recent prior hospitalization and should be targeted to the first week following hospital discharge.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Among clinical characteristics, hospitalizations with an admission for SI or SA in the preceding 30 days, meaning that the index hospitalization itself was a readmission, had the strongest association with readmissions (OR: 3.14, 95% CI: 2.73-3.61). In addition, patients admitted via the ED for the index hospitalization had higher odds of readmission (OR: 1.25, 95% CI: 1.15-1.36). Chronic psychiatric conditions associated with higher odds of readmission included psychotic disorders (OR: 1.39, 95% CI: 1.16-1.67) and bipolar disorder (OR: 1.27, 95% CI: 1.13-1.44).

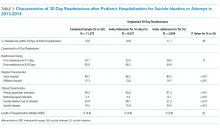

Characteristics of 30-day Readmissions

Table 3 displays the characteristics of readmissions after SI compared to that after SA. Among the combined sample of 11,375 30-day readmissions, 34.1% occurred within 7 days, and 65.9% in 8-30 days. Eleven percent of patients with any readmission had more than one readmission within 30 days. Among readmissions, 94.5% were for a psychiatric problem and 5.5% were for a medical or surgical problem. A total of 43.9% had a diagnosis of SI and 19.5% a diagnosis of SA. Readmissions were more likely to occur at a different hospital after SI than after SA (48.1% vs. 31.3%, P < .001). Medical and surgical indications for readmission were less common after SI than after SA (4.4% vs. 8.7%, P < .001). Only 1.2% of SI hospitalizations had a readmission for SA within 30 days. Of these cases, 55.6% were aged 15-17 years, 43.3% were aged 10-14 years, and 1.1% were aged 6-9 years; 73.1% of the patients were female, and 49.1% used public insurance.

DISCUSSION

SI and SA in children and adolescents are substantial public health problems associated with significant hospital resource utilization. In 2013 and 2014, there were 181,575 pediatric acute-care hospitalizations for SI or SA, accounting for 9.5% of all hospitalizations in 6- to 17-year-old patients nationally. Among acute-care SI and SA hospitalizations, 8.5% had a readmission to an acute-care hospital within 30 days. The study data source did not include psychiatric specialty hospitals, and the number of index hospitalizations is likely substantially higher when psychiatric specialty hospitalizations are included. Readmissions may also be higher if patients were readmitted to psychiatric specialty hospitals after discharge from acute-care hospitals. The strongest risk factor for unplanned 30-day readmissions was a previous hospitalization in the 30 days before the index admission, likely a marker for severity or complexity of psychiatric illness. Other characteristics associated with higher odds of readmission were bipolar disorder, psychotic disorders, and age 10-14 years. More than one-third of readmissions occurred within the first 7 days after hospital discharge. The prevalence of SI and SA hospitalizations and readmissions was similar to findings in previous analyses of mental health hospitalizations.10,28

A patient’s psychiatric illness type and severity, as evidenced by the need for frequent repeat hospitalizations, was highly associated with the risk of 30-day readmission. Any hospitalization in the 30 days preceding the index hospitalization, whether for SI/SA or for another problem, was a strong risk factor for readmissions. We suspect that prior SI/SA hospitalizations reflect a patient’s chronic elevated risk for suicide. Prior hospitalizations not for SI or SA could be hospitalizations for mental illness exacerbations that increase the risk of SI or SA, eg, bipolar disorder with acute mania, or they could represent physical health problems. Chronic physical health problems are a known risk factor for SI and SA.29

A knowledge of those characteristics that increase the readmission risk can inform future resource allocation, research, and policy in several ways. First, longer hospital stays could mitigate readmission risk in some patients with severe psychiatric illness. European studies in older adolescents and adults show that for severe psychiatric illness, a longer hospital stay is associated with a lower risk of hospital readmission.15,30 Second, better access to intensive community-based mental health (MH) services, including evidence-based psychotherapy and medication management, improves symptoms in young people.31 Access to these services likely affects the risk of hospital readmission. We found that readmission risk was highest in 10- to 14-year-olds. Taken in the context of existing evidence that suicide rates are rising in younger patients,1,3 our findings suggest that particular attention to community services for younger patients is needed. Third, care coordination could help patients access beneficial services to reduce readmissions and improve other outcomes. Enhanced discharge care coordination reduced suicide deaths in high-risk populations in Europe32 and Japan33 and improved attendance at mental health follow-up after pediatric ED discharge in a small United States sample.34 Given that one-third of readmissions occurred within seven days, care coordination designed to ensure access to ambulatory services in the immediate postdischarge period may be particularly beneficial.

We found that ZIP code income quartile was not associated with readmissions. We suspect that poverty is not as closely correlated with MH hospitalization outcomes as it is with physical health hospitalization outcomes for several reasons. Medicaid insurance historically has more robust coverage of mental health services than some private insurance plans, which might offset some of the risk of poor mental health outcomes associated with poverty. Low-income families are eligible to use social services, and families accessing social services might have more opportunities to become familiar with community mental health programs. Further, the expectation of high achievement found in some higher income families is associated with MH problems in children and adolescents.35 Therefore, being in a higher income quartile might not be as protective against poor mental health outcomes as it is against poor physical health outcomes.

Although the NRD provides a rich source of readmission data across hospitals nationally, several limitations are inherent to this administrative dataset. First, data from specialty psychiatric hospitals were not included in the NRD. The study underestimates the total number of index hospitalizations and readmissions, since index SI/SA hospitalizations at psychiatric hospitals are not included, and readmissions are not included if they occurred at specialty psychiatric hospitals. Second, because data cannot be linked between calendar years, we excluded January and December hospitalizations, and findings might not generalize to hospitalizations in January and December. Seasonal trends in SI/SA hospitalizations are known to occur.36 Third, race, ethnicity, primary language, gender identity, and sexual orientation are not available in the NRD, and we could not examine the association of these characteristics with the likelihood of readmissions. Fourth, we did not have information about pre- or posthospitalization insurance enrollment or outpatient services that could affect the risk of readmission. Nevertheless, this study offers information on the characteristics of readmissions after hospitalizations for SI and SA in a large nationally representative sample of youth, and the findings can inform resource planning to prevent suicides.