Electronic Order Volume as a Meaningful Component in Estimating Patient Complexity and Resident Physician Workload

BACKGROUND: Though patient census has been used to describe resident physician workload, this fails to account for variations in patient complexity. Changes in clinical orders captured through electronic health records may provide a complementary window into workload. We aimed to determine whether electronic order volume correlated with measures of patient complexity and whether higher order volume was associated with quality metrics. METHODS: In this retrospective study of admissions to the internal medicine teaching service of an academic medical center in a 13-month period, we tested the relationship between electronic order volume and patient level of care and severity of illness category. We used multivariable logistic regression to examine the association between daily team orders and two discharge-related quality metrics (receipt of a high-quality patient after-visit summary (AVS) and timely discharge summary), adjusted for team census, patient severity of illness, and patient demographics.

RESULTS: Our study included 5,032 inpatient admissions for whom 929,153 orders were entered. Mean daily order volume was significantly higher for patients in the intensive care unit than in step-down units and general medical wards (40 vs. 24 vs. 19, P < .001). Order volume was also significantly correlated with severity of illness (P < .001). Patients were 12% less likely to receive a timely discharge summary for every 100 additional team orders placed on the day prior to discharge (OR 0.88; 95% CI 0.82-0.95).

CONCLUSIONS: Electronic order volume is significantly associated with patient complexity and may provide valuable additional information in measuring resident physician workload.

RESULTS

Population

We identified 7,296 eligible hospitalizations during the study period. After removing hospitalizations according to our exclusion criteria (Figure 1), there were 5,032 hospitalizations that were used in the analysis for which a total of 929,153 orders were written. The vast majority of patients received at least one order per day; fewer than 1% of encounter-days had zero associated orders. The top 10 discharge diagnoses identified in the cohort are listed in Appendix Table 1. A breakdown of orders by order type, across the entire cohort, is displayed in Appendix Table 2. The mean number of orders per patient per day of hospitalization is plotted in the Appendix Figure, which indicates that the number of orders is highest on the day of admission, decreases significantly after the first few days, and becomes increasingly variable with longer lengths of stay.

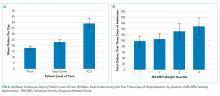

Patient Level of Care and Severity of Illness Metrics

Patients at a higher level of care had, on average, more orders entered per day. The mean order frequency was 40 orders per day for an ICU patient (standard deviation [SD] 13, range 13-134), 24 for a step-down patient (SD 6, range 11-48), and 19 for a general medicine unit patient (SD 3, range 10-31). The difference in mean daily orders was statistically significant (P < .001, Figure 2a).

Orders also correlated with increasing severity of illness. Patients in the lowest quartile of MS-DRG weight received, on average, 98 orders in the first three days of hospitalization (SD 35, range 2-349), those in the second quartile received 105 orders (SD 38, range 10-380), those in the third quartile received 132 orders (SD 51, range 17-436), and those in the fourth and highest quartile received 149 orders (SD 59, range 32-482). Comparisons between each of these severity of illness categories were significant (P < .001, Figure 2b).

Discharge-Related Quality Metrics

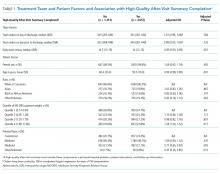

The median number of orders per internal medicine team per day was 343 (IQR 261- 446). Of the 5,032 total discharged patients, 3,657 (73%) received a high-quality AVS on discharge. After controlling for team census, severity of illness, and demographic factors, there was no statistically significant association between total orders on the day of discharge and odds of receiving a high-quality AVS (OR 1.01; 95% CI 0.96-1.06), or between team orders placed the day prior to discharge and odds of receiving a high-quality AVS (OR 0.99; 95% CI 0.95-1.04; Table 1). When we restricted our analysis to orders placed during daytime hours (7

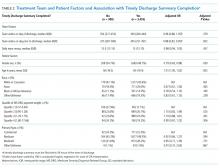

There were 3,835 patients for whom data on timing of discharge summary were available. Of these, 3,455 (91.2%) had a discharge summary completed within 24 hours. After controlling for team census, severity of illness, and demographic factors, there was no statistically significant association between total orders placed by the team on a patient’s day of discharge and odds of receiving a timely discharge summary (OR 0.96; 95% CI 0.88-1.05). However, patients were 12% less likely to receive a timely discharge summary for every 100 extra orders the team placed on the day prior to discharge (OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.82-0.95). Patients who received a timely discharge summary were cared for by teams who placed a median of 345 orders the day prior to their discharge, whereas those that did not receive a timely discharge summary were cared for by teams who placed a significantly higher number of orders (375) on the day prior to discharge (Table 2). When we restricted our analysis to only daytime orders, there were no significant changes in the findings (OR 1.00; 95% CI 0.88-1.14 for orders on the day of discharge; OR 0.84; 95% CI 0.75-0.95 for orders on the day prior to discharge).