Perspectives of Clinicians at Skilled Nursing Facilities on 30-Day Hospital Readmissions: A Qualitative Study

BACKGROUND: Unplanned 30-day hospital readmissions are an important measure of hospital quality and a focus of national regulations. Skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) play an important role in the readmission process, but few studies have examined the factors that contribute to readmissions from SNFs, leaving hospitalists and other hospital-based clinicians with limited evidence on how to reduce SNF readmissions.

OBJECTIVE: To understand the perspectives of clinicians working at SNFs regarding factors contributing to readmissions.

DESIGN AND PARTICIPANTS: We prospectively identified consecutive readmissions from SNFs to a single tertiary-care hospital. Index admissions and readmissions were to the hospital’s inpatient general medicine service. SNF clinicians who cared for the readmitted patients were identified and interviewed about root causes of the readmissions using a structured interview tool. Transcripts of the interviews were inductively analyzed using grounded theory methodology.

RESULTS: We interviewed 28 clinicians at 15 SNFs. The interviews covered 24 patient readmissions. SNF clinicians described a range of procedural, technological, and cultural contributors to unplanned readmissions. Commonly cited causes of readmission included a lack of coordination between emergency departments and SNFs, poorly defined goals of care at the time of hospital discharge, acute illness at the time of hospital discharge, limited information sharing between a SNF and hospital, and SNF process and cultural factors.

CONCLUSION: SNF clinicians identified a broad range of factors that contribute to readmissions. Addressing these factors may mitigate patients’ risk of readmission from SNFs to acute care hospitals. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2017;12:632-638. © 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Missing links: Important clinical information not effectively communicated by hospital

SNF clinicians described numerous challenges in formulating plans of care based on hospital discharge documentation. Discrepancies between discharge summaries and patient instructions were perceived as common and potential causes of readmissions. For patients discharged from the academic medical center in this study, medication instructions are included in both the discharge summary sent to the SNF and in a patient instruction packet. Several SNF clinicians said that it was common for a course of antibiotics to be listed on the discharge summary but not the patient instruction packet, or vice versa. SNF clinicians, who usually lack access to the hospital’s electronic medical record, have limited means for determining the correct document. Other important clinical data points, such as intermittent intravenous (IV) furosemide dosing and suppressive antibiotic regimens, were omitted from discharge paperwork altogether. SNF clinicians had difficulty reaching hospital clinicians who could clarify these clinical questions. “Good luck finding the person that took care of [the patient] three days before,” said one director of nursing.

Change starts at home: Challenges in SNF processes and culture

Many clinicians in our study reported that their facilities had recently added clinical capabilities in an effort to care for patients with complex medical problems. For example, to prevent transfers of patients with decompensated heart failure, several facilities in our study had recently obtained certification to give IV diuretics. However, as one director of nursing stated, these efforts require “buy-in” from doctors to decrease readmissions. That buy-in has not always been forthcoming. SNF clinicians also reported difficulty convincing patients and families that their facilities are capable of providing care that, in the past, might only have been available in acute-care settings.

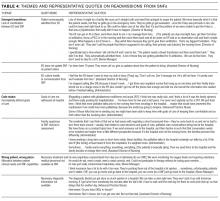

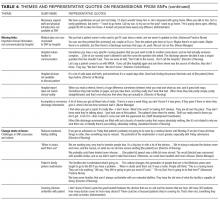

These themes, along with associated sub-themes and representative quotations, are shown above (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Our study suggests that the interaction between EDs and SNFs is an important and understudied domain in the spectrum of events leading to readmission. Prior studies have documented inadequacies in patient information provided by SNFs to EDs.16,17 Efforts to improve SNF-to-ED information sharing have focused on making sure that ED clinicians have important baseline information about patients transferred from a SNF.18,19 However, many of the clinicians in our study reported taking proactive steps to communicate with ED clinicians. These efforts encountered logistical and cultural barriers, with information that might have prevented readmission failing to reach ED providers. Many of the SNF clinicians in our study perceived this failure as a common cause of readmission, especially for relatively stable SNF patients.

Previous studies have pointed to a role for goals of care discussions in reducing hospital readmissions.20 Our data underscore an important qualification to these findings: Location matters. The SNF clinicians in our study reported frequent and detailed goals of care discussions with their patients. However, they also reported that goals of care discussions held in the subacute setting carried less weight with patients and families than discussions held in the hospital. SNF clinicians described a number of cases in which patients were willing to adjust code status or goals of care only after being readmitted to the hospital.

Our study also points to the implications of existing research showing that patients are discharged from acute care hospitals “quicker and sicker” than they had been prior to the 1983 adoption of Medicare’s prospective payment system.21 Specifically, the SNF clinicians we interviewed perceived a strong link between patient acuity at the time of transfer and SNFs’ persistently high readmission rates. As SNFs have worked to expand their clinical capabilities, they struggle to win buy-in from physicians and families, many of whom view SNFs as incapable of managing acute illness. Many SNF clinicians also pointed to deficiencies in their own referral and admission processes as a recurring cause of readmissions. For example, several patients in our analysis suffered from dementia. Although these patients were stable enough to leave the acute care setting, the SNF clinicians responsible for their readmissions felt that their SNFs were not well-equipped to care for patients with dementia and that the patients should instead have been transferred to facilities with more robust resources for dementia care.

Finally, our findings highlight a fundamental tension between hospitals and SNFs: Which facility ought to shoulder the responsibility and cost for services that may prevent a readmission—the hospital or the SNF? For example, does responsibility for coordinating subspecialist evaluation of a patient’s chronic condition fall to the hospital or to the SNF? If such an evaluation is undertaken during a hospitalization, it prolongs the patient’s hospital stay and happens at the hospital’s expense. If the patient is discharged to a SNF and sees the subspecialist in clinic, then the SNF must pay for transportation to and from the clinic appointment. SNF clinicians expressed near unanimity that fragmented models of care and high barriers to communication made it difficult to design solutions to these dilemmas.