Perspectives of Clinicians at Skilled Nursing Facilities on 30-Day Hospital Readmissions: A Qualitative Study

BACKGROUND: Unplanned 30-day hospital readmissions are an important measure of hospital quality and a focus of national regulations. Skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) play an important role in the readmission process, but few studies have examined the factors that contribute to readmissions from SNFs, leaving hospitalists and other hospital-based clinicians with limited evidence on how to reduce SNF readmissions.

OBJECTIVE: To understand the perspectives of clinicians working at SNFs regarding factors contributing to readmissions.

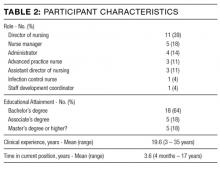

DESIGN AND PARTICIPANTS: We prospectively identified consecutive readmissions from SNFs to a single tertiary-care hospital. Index admissions and readmissions were to the hospital’s inpatient general medicine service. SNF clinicians who cared for the readmitted patients were identified and interviewed about root causes of the readmissions using a structured interview tool. Transcripts of the interviews were inductively analyzed using grounded theory methodology.

RESULTS: We interviewed 28 clinicians at 15 SNFs. The interviews covered 24 patient readmissions. SNF clinicians described a range of procedural, technological, and cultural contributors to unplanned readmissions. Commonly cited causes of readmission included a lack of coordination between emergency departments and SNFs, poorly defined goals of care at the time of hospital discharge, acute illness at the time of hospital discharge, limited information sharing between a SNF and hospital, and SNF process and cultural factors.

CONCLUSION: SNF clinicians identified a broad range of factors that contribute to readmissions. Addressing these factors may mitigate patients’ risk of readmission from SNFs to acute care hospitals. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2017;12:632-638. © 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Analysis

Analysis of transcripts was inductive and informed by grounded theory methodology, in which data is reviewed for repeating ideas, which are then analyzed and grouped to develop a theoretical understanding of the phenomenon under investigation.13,14

A preliminary codebook was developed using transcripts of the first 11 interviews. All statements relevant to the readmission process were extracted from the raw interview transcript and collected into a single list. This list was then reviewed for statements sharing a particular idea or concern. Such statements were grouped together under the heading of a repeating idea, and each repeating idea was assigned a code. Using this codebook, each transcript was independently reviewed and coded by three study team members with formal training in inductive qualitative analysis (KB, KTM, BWC). Reviewers assigned codes to sections of relevant text. Discrepancies in code assignment were discussed among the 3 analysts until consensus was reached. Using the method of constant comparison described in grounded theory,the codebook was updated continuously as the process of coding transcripts proceeded.12 Changes to the codebook were discussed among the coding team until consensus was achieved. The process of data acquisition and coding continued until theoretical saturation was reached. Themes relating to underlying factors associated with readmissions were then identified based on shared properties among repeating ideas. ATLAS.ti (Scientific Software, Berlin, Germany, Version 7) was used to facilitate data organization and retrieval.

RESULTS

The SNFs in our study included 12 for-profit and 3 non-profit facilities. The number of licensed beds in each facility ranged from 73 to 360, with a mean of 148 beds. The SNFs had CMS Nursing Home Compare ratings ranging from 1 star, the lowest possible rating, to 5 stars, the highest possible,15 with a mean rating of 2.9 stars. Our analysis did not reveal differences in perceived contributions to readmissions from large vs. small or highly rated vs poorly rated SNFs.

The patients in our analysis represented a highly comorbid and medically complex population (Table 3). Many had barriers to communication with clinical staff, including non–English-speaking status and underlying dementia.

Five main themes emerged from our analysis: (1) lack of coordination between EDs and SNFs; (2) incompletely addressed goals of care; (3) mismatch between patient clinical needs and SNF capabilities; (4) important clinical information not effectively communicated by hospital; and (5) challenges in SNF processes and culture.

Emergent transitions: Lack of coordination between ED and SNF

SNF clinicians frequently encountered situations in which a relatively stable patient was readmitted to the hospital after being transferred to the ED, despite the fact that SNF clinicians believed the patient should have returned to the SNF once a specific test was performed or service rendered at the ED. Commonly cited clinical scenarios that resulted in such readmissions included placement of urinary catheters and evaluation for cystitis. An assistant director of nursing reported that “the ER doesn’t want to hear my side of the story,” making it difficult for her to provide information that would prevent such readmissions. Other SNF clinicians reported similar difficulties in communicating with ED clinicians.

Code status: Incompletely addressed goals of care

The SNF clinicians in our study described cases in which patients with end-stage lung disease and disseminated cancer were readmitted to the hospital, despite SNF efforts to prevent readmission and provide palliative care within the SNF. For example, a SNF advanced practice nurse described a case in which a patient with widely metastatic cancer requested readmission to the hospital for treatment of deep vein thrombosis, despite longstanding recommendations from SNF staff that the patient forego hospitalization and enroll in hospice care. After discussion of code status and goals of care with hospital clinicians, the patient chose to enroll in hospice care and not to continue anticoagulation. SNF clinicians often perceived that, in the words of one administrator, “the palliative talks in the hospital outweigh our talks by a lot.” Numerous SNF clinicians believed that in-depth clarification of goals of care prior to discharge could prevent some readmissions.

Wrong patient, wrong place: Mismatch between clinical needs and SNF capabilities

One director of nursing stated that “[when] you read a referral, there’s a huge difference sometimes between what you read and what you see.” SNF clinicians reported that this discrepancy between clinical report and clinical reality often leads to patients being placed in SNFs that are unequipped to care for them. Many patients were perceived as being too ill for discharge from the acute-care setting in the first place. A nurse manager described this as a pattern of “pushing patients out of the hospital.” However, mismatches in clinical disposition were also seen as contributing to readmissions for medically stable patients, such as those with dementia, for whom SNFs frequently lack adequate staffing and physical safeguards.