Gap analysis: a strategy to improve the quality of care of head and neck cancer patients

Background Continuing assessment of cancer care delivery is paramount to the delivery of high-quality care. Head and neck cancer patients are vulnerable to flaws in care because of the complexity of medical and psychosocial conditions.

Objective To describe the use of a gap analysis and quality improvement interventions to maximize the coordination and care for patients with head and neck cancer.

Methods The gap analysis was comprised of a thorough literature review to determine best practice in the management of head and neck cancer patients and data collection on the care provided at a cancer center. Data collection methods included a clinician survey, a process map, and a patient satisfaction survey, and baseline data from 2013. A SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) analysis was conducted, followed with quality improvement interventions. A re-evaluation of key data points was conducted in 2015.

Results Through the clinician survey (n =25 respondents) gaps in care were identified and included insufficient preoperative education, inefficient discharge planning, and delayed dental consultations. The patient satisfaction survey indicated overall satisfaction with the care received at the cancer center. The process mapping (n =33 respondents) identified that the intervals between treatments did not always meet the best practice standards. The re-assessment revealed improvement with the process for nonsurgical patients by meeting the benchmark.The surgical cases revealed the interval between surgery and initiation of treatment was greatly improved, although it did not yet meet the benchmark.

Limitations Small sample size

Conclusions A gap analysis provides the structure to evaluate and improve cancer care services for head and neck cancer patients.

Accepted for publication January 9, 2017. Correspondence Mary Pat Lynch, MSN, CRNP, AOCNP; LynchMP@pahosp.com. Disclosures The authors report no disclosures or conflicts of interest.

JCSO 2017;15(1):28-36. ©2017 Frontline Medical Communications.

doi: https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0324.

Patients were typically referred to outpatient nutrition at the start of radiation therapy. In the initial assessment, all patients (n = 33) had access to nutrition services, but 21% (n = 7) never spoke to the nutritionist. The re-assessment found all but one (n = 7) of the patients had been seen by a nutritionist at some point during the treatment period. The benchmark of preradiation nutrition assessment was met by 2 postsurgical patients, with the remainder of the patients being seen within 3 days of the initiation of radiation.

Speech-language pathology management. The literature recommends that patients receive SLP management before the surgery.14-17 In this gap analysis, a difference in access to SLP services was identified between inpatient and outpatient settings. On average, patients within the sample were referred to outpatient SLP over a month after their surgery. In contrast, inpatient surgical patients had access to rapid consultations with SLP (eg, 1 day after surgery for total laryngectomy, and 4 days after surgery for oropharyngeal and oral surgery patients; T Hogan, unpublished data, June 2014). Overall, the benchmark was not met, as patients were not seen by the SPL prior to treatment.

New baseline data was collected about SLP services and showed that 70% of patients had contact with the outpatient SLP at some point during their treatment. Of those, only 29% of patients saw SLP before surgery, meeting the benchmark. The baseline waiting time was an average of 15 days before surgery and 43 days after surgery. Overall, the trend is moving toward the benchmark of care.

,Similarly, studies determined that the gold standard of care for nonsurgical patients is that SLPs begin pretreatment management of HNC.16Patients in the baseline sample were typically referred to outpatient SLP about a month after biopsy (presumably diagnosis), but before the start of chemo-radiation. There were no data available for the number of patients who were actually seen by the outpatient SLP before the start of chemo-radiation.

The new baseline data found that 100% of nonsurgical patients were referred to SLP, but only25% (n = 2) were seen before they started chemo-radiation therapy (an average 5 days before) and 75% (n = 6) were seen after starting chemo-radiation therapy (an average 23 days after).

SWOT analysis

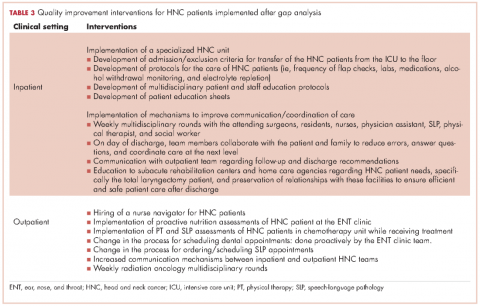

The SWOT analysis included strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats of the care provided to HNC patients at the cancer center. The gap analysis based on the results of the clinician surveys, process mapping, and patient satisfaction survey is summarized in Table 3. Three main gaps were identified: waiting time to treatment, education, and coordination of and transitions in care.

Quality improvement actions

Interventions by the outpatient MTD team included changing the process of scheduling dental appointments, creating a new approach to outpatient nutrition by proactively meeting patients in the ENT clinic, and conducting PT and SLP assessments to patients in the chemotherapy unit while receiving their treatment. A nurse navigator position for this patient population was approved and an expedited referral system was initiated. At the same time, the inpatient team implemented a specialized HNC unit in the medical-surgical floor, developed the protocols for the management of postsurgery HNC patients, educated nursing staff, and standardized patient education to facilitate transition to the next level of care (Table 3).

Discussion

The gap analysis of services provided to HNC patients at the cancer center identified three gaps in care: delay in treatment and supportive services, nonstandardized patient education, and lack of care coordination.

All patients should have access to a timely treatment initiation. In this analysis, surgical patients encountered a delay between surgery and the start of radiation therapy, about 3 weeks beyond the recommended in the literature.12 Clinicians mentioned delays in ensuring preradiation dental consultations as a significant issue affecting the patient treatment process. Re-assessment data reported that despite interventions for early dental referrals, 80% of patients still started radiation over 6 weeks after surgery; however, the average time lag decreased from 68 days to 53 days.

RT delays in HNC patients not only affect patients’ emotional state but may also impact clinical outcomes. Treatment delays have the potential to harm patients by: allowing tumor growth that impact on the curative outcomes of RT; postponing the benefits of palliative RT on symptom relief; and causing psychological distress.25 In addition, delay in starting treatment has shown to increase the risk for local recurrence,13,26 and decrease survival.27

Higher demand for advanced RT modalities has been linked to treatment delays. Waiting times from initial RT evaluation to start RT have increased over time, from <14 days in 1989 to 31 days in 1997.11 This is explained by the complexity of the pretreatment evaluations and the increasing demand of radiation services, especially in high volume institutions.25,27A fast-track program to reduce waiting time in the treatment of HNC patients reported to be effective.22 This program includes a patient coordinator, a hotline for referral procedures, prebooked slots for ENT and RT clinics, faster pathology and imaging reports, and the establishment of an MTD team.

The clinician survey identified patient needs classified in three categories: pre-operative education, hospitalization process, and access to support services. Regarding pre-operative education, clinicians acknowledged that although patients were educated about their surgical options and possible outcomes prior to hospitalization, they often could not fully understand this information at the time of the instruction. The high need for education particularly in the pretreatment phase was documented in a needs assessment survey for HNC patients conducted at the cancer center D DeMille, RD, unpublished data, August 2013).

Studies have looked at the effectiveness of education in cancer patients. The use of teaching interventions (written information, audiotapes, videotapes, and computer programs) has proven to be valuable for educating patients prior to experiencing cancer treatments.20Further, a systematic review of preparatory education for cancer patients undergoing surgery reported that face-to-face discussions appear to be effective at improving patient outcomes with regards to increasing knowledge and decreasing anxiety.21 However, it was stated that the timing of the delivery of education is critical to be efficient. For example, an education session provided one day prior the day of surgery is not useful as it may place additional stress on a patient who is already highly anxious and decreases the likelihood for the information to be managed. It is recommended to deliver education early enough prior surgery to allow time for the patient to process the information. Also, a study reported that presurgical education on potential side effects; the assessment of patients’ needs by an SLP, physical therapist, nutritionist, and social worker; and pre-operative nutritional support decrease postoperative complications.4

The education committee was created in response to the gap on patient education. The inpatient team took the lead and provided intense education on the care of HNC patients to the nursing staff and to HNC patients and their families about postoperative care at home. Education was also extended to rehabilitation facilities caring for this cancer population at discharge from the hospital.

Clinicians identified a gap during the hospitalization process. The gap included prolonged stay of patients in the ICU postsurgery, inefficient interclinician communication, lack of standardization of postsurgical care, and difficulty communicating with external home care teams. A major intervention was implemented that included the creation of a HNC specialized unit that offered a structured setting for standardized care and communication between patients and clinicians. Dedicated units for the management of HNC patients highly enhance the quality of care provided because it enables the MTD team to work properly by clearly defining roles and responsibilities, delineating evidence-based clinical interventions, and promoting expert care for this patient population.23In addition, several key steps have been recommended to reduce the fragmentation of care for hospital patients, including developing a referral/transition tracking system, organizing and training staff members to coordinate transition/referrals, and identifying and creating agreements with key care providers.28

Early patient access to supportive services was a concern to most clinicians. HNC providers were not consulting the CARE clinic about patients’ nutritional, physical and SLP needs until the patient was having serious problems. Patient tracking found that the minority of patients met the standard of having a presurgical speech referral. Most patients had access to outpatient nutrition services during radiation therapy but the majority of patients in the sample did not attend CARE clinic. The literature strongly supports early management of HNC patients by the SPL and nutrition counselor. Van der Molen and colleagues demonstrated that a pretreatment SPL rehabilitation program is feasible and offers reasonable patient compliance despite of the burden caused by ongoing chemo-radiation therapy for HNC patients.16Similarly, early nutrition counseling for HNC patients undergoing RT has reported to decrease unintended weight loss and malnutrition compared with late nutrition intervention.19

Although there are clear gaps in care for HNC patients from the clinicians’ perspective, the patients surveyed indicated a clear satisfaction with their care at the cancer center. Almost all patients were satisfied with their relationships with clinicians in the team. Some patients mentioned complaints of insufficient pre-operative education and waiting time, but there were not significant complaints about coordination, which clinicians had identified as a major issue. This is likely explained by the small sample size and the patients’ inability to see the background interclinician communication.

A crucial suggestion to address all of these gaps in care was the implementation of a nurse navigator. With the support of hospital and cancer center administration, a nurse navigator was hired to address the needs of HNC patients throughout their disease trajectory. The team agreed that the nurse navigator should make contact with HNC patients during their initial appointment at the surgical ENT office. This initial contact allows the nurse navigator to provide support and connection to resources. Thereafter, early contact with this patient population allows the nurse navigator to follow the patient through the continuum of care from biopsy and diagnosis to survivorship. The nurse navigator facilitates communication between clinicians, patients and their families; and provides emotional support to patients while helping to manage their financial and transportation needs.29