Gap analysis: a strategy to improve the quality of care of head and neck cancer patients

Background Continuing assessment of cancer care delivery is paramount to the delivery of high-quality care. Head and neck cancer patients are vulnerable to flaws in care because of the complexity of medical and psychosocial conditions.

Objective To describe the use of a gap analysis and quality improvement interventions to maximize the coordination and care for patients with head and neck cancer.

Methods The gap analysis was comprised of a thorough literature review to determine best practice in the management of head and neck cancer patients and data collection on the care provided at a cancer center. Data collection methods included a clinician survey, a process map, and a patient satisfaction survey, and baseline data from 2013. A SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) analysis was conducted, followed with quality improvement interventions. A re-evaluation of key data points was conducted in 2015.

Results Through the clinician survey (n =25 respondents) gaps in care were identified and included insufficient preoperative education, inefficient discharge planning, and delayed dental consultations. The patient satisfaction survey indicated overall satisfaction with the care received at the cancer center. The process mapping (n =33 respondents) identified that the intervals between treatments did not always meet the best practice standards. The re-assessment revealed improvement with the process for nonsurgical patients by meeting the benchmark.The surgical cases revealed the interval between surgery and initiation of treatment was greatly improved, although it did not yet meet the benchmark.

Limitations Small sample size

Conclusions A gap analysis provides the structure to evaluate and improve cancer care services for head and neck cancer patients.

Accepted for publication January 9, 2017. Correspondence Mary Pat Lynch, MSN, CRNP, AOCNP; LynchMP@pahosp.com. Disclosures The authors report no disclosures or conflicts of interest.

JCSO 2017;15(1):28-36. ©2017 Frontline Medical Communications.

doi: https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0324.

In addition, they identified the hospitalization and/or home care phases as areas for potential improvement. During hospitalization, patients often expressed surprise upon learning that they had a feeding tube and/or tracheostomy despite having received pre-operative education. This misunderstanding by the patient was likely related to the clinicians’ assumptions about the best timing for patient education and the amount of time needed for education before the surgical procedure. The surgical team provided patient education based on individual needs, and it has not been standardized because they felt that patients’ education needs vary from person to person. In contrast, patient education prior radiation therapy is standardized, and all patients received a comprehensive package of information that is re-enforced by direct patient education by the clinicians.

Another gap in care identified by the inpatient team was a prolonged intensive care unit (ICU) stay for the HNC patients. These patients remained in the ICU for the entirety of their stay. Not only was this causing overuse of resources, but patients also felt unprepared for an independent discharge home given the high level of care received in the ICU.

A range of suggestions were made to solve these problems. The most prevalent suggestion was to use a nurse navigator to coordinate referrals, schedule appointments, facilitate interdisciplinary communication, and to address social, financial, and transport needs for HNC patients. Several other suggestions referred to standardizing treatment procedures and pre-operative patient education.

,Patient survey

Forty-three patients were identified for the patient satisfaction survey. Each patient was contacted at least three times over the course of 3 weeks. Of the 43 patients, 20 had an invalid phone number, 10 were not available for participation, and 1 declined to participate. A total of 12 patients completed the survey.

Although the sample size was small, the patients surveyed were very satisfied with their care. Of the 12 patients, 5 patients rated all of the services relevant to their treatment as a 5 (Great). Areas of particular concern for the patients included the waiting time to see a physician in the ENT clinic, the explanation/collection of charges, and the accessibility of support groups. Services rated 3 (Satisfactory) included waiting time to schedule appointments; the amount of information and patient education provided by about radiation, nutrition, physical therapy (PT), occupational therapy (OT), and SLP; and overall satisfaction with care.

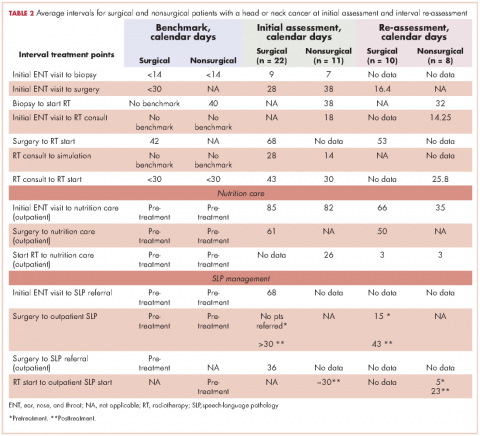

Surgical patients. The Danish Head and Neck Society guidelines state that the interval between the initial visit diagnosis and surgery should be within 30 days.12A comparison of the average intervals between important treatment points for the surgical sample patients with the benchmark timing recommended in the literature are shown in Table 2. The mean time from initial visit to surgery was 28 days in the cancer center sample; 67% of patients (n = 14) had surgery within 30 days, and 33% of patients (n = 7) had surgery beyond 30 days. The interval re-assessment showed improvements in this area: the mean time from initial visit to surgery went from 28 to 18 days, and 100% of patients

n = 10) had surgery within 30 days.

Huang and colleagues have indicated that postoperative radiation therapy should ideally occur within 42 days of surgery;13 however, in the present study, 79% (n = 11) of the sample surgical patients undergoing radiation began their therapy on average more than 63 days after surgery. The interval re-assessment found the same results with 80% of patients starting radiation over 42 days after surgery although the average time lag decreased from 68 days to 53 days.

Nonsurgical patients. Huang and colleagues have indicated that for patients undergoing radiation as their primary form of treatment, an interval of 40 days between biopsy and the start of radiation is ideal.13 The average intervals between important time points of treatment for patients who did not require surgery in their treatment are shown in Table 2. The cancer center met the benchmark at baseline with an average of 38 days (n = 11 patients). The re-assessment showed improvement in this area with 100% of cases (n = 10) meeting the benchmark with an average of 32 days. Likewise, the benchmark waiting time from RT consultation to RT start of less than 30 days11 was met by the cancer center for the nonsurgical group (n = 11).

Access to supportive services

Nutrition care. Studies have shown that standard nutritional care for HNC patients should start before treatment.18,19 In the present study, the waiting time from surgery to outpatient nutrition assessment improved from 61 days to 50 days (Table 2). For patients in the surgical group, the time interval between the initial ENT visit to the outpatient nutrition assessment decreased from 85 days at baseline to 66 days at reassessment, and 82 days to 35 days, respectively, for the nonsurgical group. The time interval from surgery to nutrition assessment has not reached the recommended pretreatment benchmark, but data showed a trend of improvement from 61 days at baseline to 50 days at reassessment for patients in the group.