Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Epidemiology, Clinical Presentation, and Evaluation

Clinical Presentation

COPD is heterogeneous in its presentation. Based on data from NHANES III, 44% of patients with severe airflow limitation (FEV1 < 50% of predicted) may not report symptoms [3]. Among patients with severe airflow limitation who do report symptoms, the symptoms reported most frequently include wheezing (64%) and shortness of breath (65%).

In recent years, COPD has been increasingly recognized as a systemic illness, with effects on nutritional status, muscle wasting, and depression [56–58]. A large proportion of patients probably have components of chronic bronchitis, asthma, and emphysema occurring together. Although some of this overlap may be related to misdiagnosis, some of it may be a measure of the presence of airflow limitation reversibility, as described above. Better defining individuals in these groups may ultimately help tailor better interventions.

Some of the barriers to COPD diagnosis and subsequent treatment often include insufficient knowledge and awareness about COPD especially among primary care physicians, misdiagnosis of COPD as other respiratory diseases such asthma, as well as patient-related barriers involving lack of awareness of early symptoms of COPD and considering them to be related to aging or smoking [59].

Evaluation

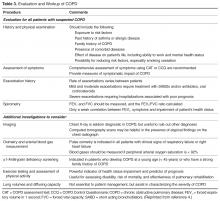

The evaluation of a patient with suspected COPD is oriented toward establishing the correct diagnosis and, once this has occurred, determining the extent of the impairment such that therapy can be appropriately targeted.

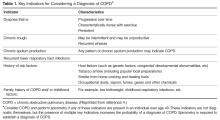

Components in the evaluation of COPD are listed in Table 3. Every patient with suspected COPD should undergo a thorough history and physical examination. The history should pay particular attention to the following: exposure to risk factors; past history of asthma or allergic disease; family history of COPD; presence of comorbid diseases; effect of disease on the patient’s life, including ability to work and mental health status; and possibilities for reducing risk factors, especially smoking cessation [4]. The physical examination is rarely diagnostic in COPD because most physical abnormalities do not occur until the advanced stages of the disease. Physical examination findings in

Pulmonary function testing is a critical part of the evaluation of suspected COPD. Whereas most patients with COPD can be managed by a primary care physician, patients with moderate or severe COPD should be evaluated by a specialist [4].

Once the diagnosis of moderate or severe COPD has been established, further testing, including chest radiograph, arterial blood gas determination, screening for α1-antitrypsin deficiency, 6-minute walk testing or exercise oxymetry may be indicated based on the patient’s history and/or clinical findings. Data from computed tomography scans are useful in some advanced cases.

Prognosis of COPD is often influenced by presence of various comorbidities including extrapulmonary, such as osteoporosis, metabolic syndrome, and depression that may be seen as parts of multimorbidity associated with aging [60,61]. Therefore, it is advised to look for comorbidities in COPD patients with any severity of airflow obstruction and treat them accordingly [4].

Therapy for COPD targets reducing risk factors, improving symptoms, and decreasing the risk of exacerbations [10]. Interventions include smoking cessation, vaccinations, decreasing exposures to occupational and environmental pollutants, pulmonary rehabilitation, bronchodilators, and corticosteroids. Select patients with advanced COPD may benefit from other interventions, such as surgical reduction of lung size, lung transplant, the phosphodiesterase inhibitor roflumilast and chronic treatment with antibiotics such as macrolides.