Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Epidemiology, Clinical Presentation, and Evaluation

Definition and Classification

Several different definitions have existed for COPD [4–8]. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), an international collaboration of leading experts in COPD launched in the late 90s with a goal to develop evidence-based recommendations for diagnosis and management of COPD [4], currently defines COPD as “a common, preventable and treatable disease that is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation that is due to airway and/or alveolar abnormalities usually caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases” [4].

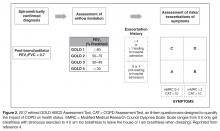

Severity of COPD has typically been determined using the degree of lung function impairment, although the wisdom of this approach has been questioned,

Previous definitions of COPD differentiated between chronic bronchitis, asthma, and emphysema, acknowledging that there is frequently overlap between these disease entities [12,13]. The GOLD definition of COPD does not differentiate between chronic bronchitis and emphysema but does note that although asthma and COPD can coexist [4], the largely reversible airflow limitation in asthma merits different therapeutic approaches than the largely irreversible airflow limitation of COPD. The overlap of asthma and COPD in a significant proportion of patients has been the focus of recent work [14].

Epidemiology

Prevalence of COPD

The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) is an ongoing national random-digit-dialed telephone survey of landline and cellphone households designed to measure behavioral risk factors for the noninstitutionalized adult population of the US [15]. An affirmative response to the following question was defined as physician-diagnosed COPD: “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), emphysema, or bronchitis?”[16]. Based on 2011 BRFSS survey, 13.7 million adults aged ≥ 25 years were estimated to have a self-reported physician diagnosis of COPD in the United States. The greatest age-adjusted prevalence was found to be clustered along the Ohio River Valley and the southern states [16].

The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) is an annually conducted, nationally representative survey of the civilian noninstitutionalized population aged 18 years and older. A positive response to one or both of the following questions was used to define COPD: “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had emphysema?” and “During the past 12 months, have you been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had chronic bronchitis?” Age-adjusted COPD prevalence estimates showed significant interyear variation during 1999–2011 period, and were higher in women than in men with the highest prevalence noted in 2001 for both genders [16].

The NHIS estimates for COPD have 2 important limitations. First, these estimates depend on the proper recognition and diagnosis of COPD by both the study participants and their health care providers. This would tend to bias the estimates toward counting fewer cases than actually exist. A bias in the opposite direction, however, is that the term chronic bronchitis in this survey is not precisely defined and could be interpreted as recurrent episodes of acute bronchitis. The finding that “chronic bronchitis” has been reported in 3% to 4% of children supports the presence of this potential bias. The second limitation is that this survey is not able to validate, through physiologic evaluation, whether airway obstruction is present or absent.

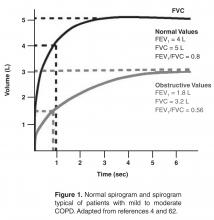

These limitations were addressed, in part, by separate nationally representative US surveys that include an examination component, such as the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) [17]. An analysis of these data from 1988–1994 and 2007–2012 [18] demonstrated that over 70% of people with evidence of obstruction (based on an FEV1/FVC < 70%) did not have a diagnosis of lung disease (COPD or asthma). In addition, people with evidence of obstruction had a higher risk of mortality whether or not they had diagnosed lung disease [18].

Evaluation of “reversibility” of the airway obstruction requires the administration of bronchodilator, which is not a part of most population-based studies. A subset of participants in the NHANES 2007–2012 survey received a bronchodilator, with a decrease in the estimated prevalence of obstruction from 20.9% to 14.0% [19]. However, a closer look at similar data from a study where all people got a bronchodilator reveal that only a small proportion of people with “reversibility” actually had a significant response to the bronchodilator [20]. In a clinic-based study of subjects with COPD who were aged 69 years and older, 31% demonstrated reversibility, defined as a 15% improvement (from baseline) in FVC and FEV1 following administration of an inhaled bronchodilator [21]. In this study, subjects with more severe obstruction were more likely to have reversibility but would also be more likely to continue to have diminished lung function after maximum improvement was obtained, thus being classified as having “partial reversibility.”

The presence of significant reversibility or partial reversibility in patients with COPD [15] and nonreversible airflow obstruction in asthma patients [22] demonstrates that these diseases can coexist or, alternatively, that there is overlap and imprecision in the ways that these diseases are clinically diagnosed.