Adverse events from systemic treatment of cancer and patient-reported quality of life

Background Treatment-related adverse events (AEs) have a negative impact on the quality of life (QoL) of cancer patients. Patient and general public views can help in the investigation of patient needs and preferences.

Objective To compare the impact on QoL reported by cancer patients who have experienced a particular AE with that envisioned by general public participants (hypothetical patients) who have not experienced AEs.

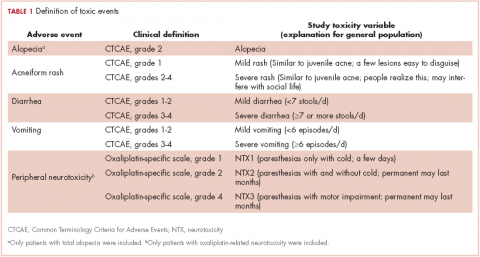

Methods Five AEs were selected: total alopecia (Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events [CTCAE] grade 2), acneiform rash (CTCAE, grade 1 and grades 2-4), oxaliplatin-associated peripheral neuropathy (oxaliplatin-specific scale, grades 1, 2, and 4); diarrhea and vomiting (CTCAE, grades 1-2 and grades 3-4), resulting in 10 toxicity variables. Cancer patients and general public participants completed the Visual Analog Scale (VAS; 0 = poorest QoL; 100 = better QoL), and cancer patients also completed the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire (full range for Spanish population, -0.654-1.000).

Results 246 general public participants and 200 toxic events in 139 cancer patients were analyzed. For all 10 endpoints, the mean VAS was higher for patients than for the general public participants. That difference was statistically significant (Mann-Withney U test) for all endpoints except for grade 1 neuropathy and grade 1 rash. For both groups, alopecia had a lower impact on quality of life than did severe rash (mean VAS for patients, 77 [alopecia] vs 59 [rash], compared with 55 vs 47, respectively, for the general public group). There was a positive linear correlation between the EQ-5D-5L and VAS (Spearman rho, 0.681; P = .001).

Limitations Patients were asked to score AEs as separate and encapsulated from other concurrent symptoms. This exercise may be rather difficult for patients.

Conclusions The impact of therapy-related AEs on QoL was lower in patients who have experienced the AEs than it was for the general public participants who had not experienced the AEs. The EQ-5D-5L is a useful tool for evaluating AEs.

Funding/sponsorship Provided by the Oncologic Association Dr Amadeu Pelegrí (AODAP), a charitable organization led by cancer patients and based in Salou, Spain.

Accepted for publication July 14, 2017

Correspondence Vicente Valentí, PhD; vvalenti@xarxatecla.cat

Disclosures The authors report no disclosures/conflicts of interest.

Citation JCSO 2017;15(5):e256-e262

©2017 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0364

Submit a paper here

Adverse events (AEs) from systemic treatment of cancer have a negative impact on patient quality of life (QoL). The extent of this impact is difficult to ascertain, particularly in patients undergoing palliative treatment because of variations in QoL resulting from antitumor effect.1 Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are the best tool for elicitation of patient preferences, therefore helping cancer patients, oncologists, and health care managers to make better choices. Indeed, analysis of self-reported QoL during cancer chemotherapy provides new insights that are missed by other efficacy outcomes,2 although patient-reported AEs correlate well with AEs reported by clinicians.3 Self-reported symptoms provide better control during cancer treatment.4 However, there are other instruments to measure the impact of treatments on QoL that are based on preferences of members of the general public. Use of that strategy has been strongly debated. The most obvious problem is the difficulty that persons from the general public may have in putting themselves in the patient position.5 In addition, there is evidence that compared with the general public, patients adapt to their illness5,6 and then tend to downplay severity when rating values of health states.7 Therefore, a systematic discrepancy is observed between actual patients and the general public. It is not clear if it reflects the inability of members of the general public to fully grasp the relative severity of health problems or to the adaptation process of patients. This fact may obscure a negative impact on QoL which, in turn, could be detected using the general public as a surrogate. A combination of both approaches has been recommended for rating QoL when the ultimate purpose is making decisions on resource allocation.5 This debate is prolonging in time and it is far from over.8,9

Based on this background, this study investigates the impact of AEs on QoL of cancer patients from the perspective of cancer patients who had experienced the AEs of interest (ex post population) and the perspective of members of the general public. The second group comprised participants imagining themselves as hypothetical cancer patients experiencing the AEs (ex ante population). Previous studies with this dual approach allowing for comparisons between these two populations are small or centered on a few AEs.10 Therefore, a large and comprehensive study on the impact of AEs on QoL is lacking. Supported by previous literature, the investigational hypothesis was that ex post impact would be significantly lower than that imagined in an ex ante setting. The secondary objective is to study the potential use of the EuroQol (EQ-5D) instrument for health-related QoL in the measurement of the impact of AEs in cancer patients. This generic instrument is based on interviews with members of the general public. We tried to investigate to what extent those values relate to the cancer patients’ evaluation of their own health during treatment. The ultimate goal of the study is to assist in increasing the utility that patients derive from the benefits associated with cancer treatment.

Methods

Selection of AEs

Five AEs related to systemic treatment of cancer – alopecia, acneiform rash, oxaliplatin-associated peripheral neuropathy, diarrhea, and vomiting – were selected for the study. Investigators set up different relevant cut-off points for severity, resulting in 10 toxic events that were ad hoc defined as the variables for the study (Table 1). We used the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE, version 4) to classify alopecia, acneiform rash, diarrhea, and vomiting. For oxaliplatin-associated peripheral neuropathy, we adapted Misset’s oxaliplatin-specific scale11 (range, grade 1-4; Table 1) in which grade 1 (neurotoxicity [NTX] 1) = paresthesias only with cold lasting a few days; grade 2 [NTX2] = paresthesias with and without cold that may last months; and grade 4 [NTX3] = paresthesias with functional consequence).

,Participants

Two populations were included in the study: cancer patients who had experienced a particular AE and received treatment at the medical oncology departments of Hospital Santa Tecla and Hospital del Vendrell in Tarragona, Spain; and participants from the general public who received care at the Primary Health Care Center-Llevant in the same city.

Cancer patients. These participants had to be 18 years or older and had to have experienced 1 of the 10 toxic events in the 5 years before inclusion in the study; the treatment setting could be either curative attempt (adjuvant, neoadjuvant) or palliative, and patients with ongoing treatment should have received almost 3 months of treatment. Patients were excluded if they had an ECOG PS grade of 3 or more (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; range, 0-5, where 0 = fully active, 3 = capable of limited self-care; confined to bed or chair more than 50% of waking hours, and 5 = dead). A particular patient with cancer could be included because of more than 1 study toxic event (eg, alopecia and severe vomiting or NTX1 and NTX2) but had to complete separate questionnaires for the different toxic events.

General public group. Participants in this group were selected from the records of general practitioner consultations at the aforementioned primary health care center. They had to be 18 years or older and could not have a history of cancer or symptomatic/severe chronic diseases (eg, they could have hypertension or diabetes without chronic target organ involvement, or they could be patients with either acute nonserious illness or nonserious injuries).