Point of prostate cancer diagnosis experiences and needs of black men: the Florida CaPCaS study

Background Black men are disproportionately affected by prostate cancer and little is known about their experiences at the point of prostate cancer diagnosis (PPCD). Men who self-identify as black are commonly treated in a singular cohort even though they may be of diverse ethnic origin. This is especially important given the increasing number of foreign-born blacks in the United States.

Objective To examine the experiences and needs of ethnically diverse black men at the PPCD to develop an interpretative framework.

Method The research population was black men who had been diagnosed with prostate cancer during 2006-2010. We used a qualitative research design based on grounded theory principles. Using a semistructured interview guide, a trained interviewer collected data on the participants’ PPCD experiences. The data analyses included verifying the narrative data, coding data, and developing an interpretative framework.

Results From an initial sample of 212 black men, data were collected from 31 participants. The interpretative framework that emerged from the study describes the status of black men at the PPCD, experiences of black men at the PPCD, and emotional reactions of black men at the PPCD. Of note is the need among men at the PPCD for psycho-oncology support, emotional support, and time to reflect on the diagnosis.

Limitations Men with different experiences may have chosen not to respond to recruitment efforts or refused participation in the study.

Conclusion The framework provides information that physicians can use to help their patients cope at the PPCD.

Funding Department of Defense PCRP Award W81XWH1310473.

Accepted for publication December 5, 2016. Correspondence Folakemi Odedina, PhD; fodedina@cop.ufl.edu. Disclosures The authors report no disclosures or conflicts of interest.

JCSO 2017;15(1):10-19. ©2017 Frontline Medical Communications.

doi: https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0323.

Cognitive, emotional, and behavioral coping experiences

As expected, there were ranges of emotions, including shock, disbelief and denial (Table 4). Some of the men questioned why this (the cancer) was happening to them when they had done “nothing” to deserve it. Doing nothing in this case meant that they had lived a healthy lifestyle with no obvious apparent cause to have the cancer. Fear and cancer fatalism were experienced by a significant number of the men, with their thoughts immediately turning to death and dying. This was especially the case for men who had lost a loved one to cancer. Conversely, some of the men wanted immediate resolution, focusing instead on ways to beat the cancer and with a strong will to live.

Reliance on faith was a big part of coping at the PPCD. Some of the men drew strength from their faith to get them through their cancer journey. Others found a way to accept the diagnosis – one participant accepted the diagnosis and the fact that this could mean dying (after living a good life), whereas another participant accepted the diagnosis with the hope that he would find a cure. Hope was more realistic with the knowledge that other men had survived prostate cancer.

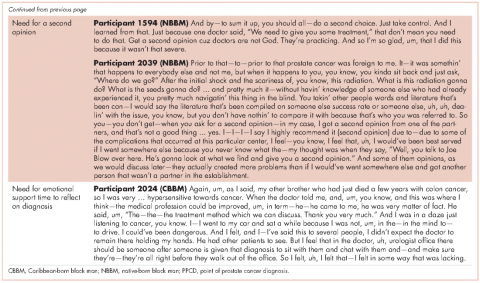

Reflecting back on their experiences, the men also identified clear needs at the PPCD. One of the needs they identified was having a physician they were comfortable with to discuss their diagnosis. Another need was for a second opinion. Participant 1594 (NBBM) advised that it was important for black men to take control by requesting a second opinion. Participant 2039 (NBBM) described a feeling of navigating blindly and trying to find answers that would be helpful to him in his cancer journey. However, his experience with a second opinion was not helpful because the second physician was at the same clinic as his primary physician. His recommendation was to get a second opinion at a different clinic or center. Another important need was emotional support at the PPCD. Participant 2024 (CBBM) made a strong case for emotional support, especially for men who are not accompanied during diagnosis. In addition, Participant 2024’s (CBBM) reflections underscore the fact that the PPCD may not be an ideal place or time to discuss treatment options. With the range of emotions that the men go through at the PPCD, it is difficult to comprehend any follow-up discussions after hearing the words “you have prostate cancer.” Participant 2024 (CBBM) also strongly expressed that men need time to deal with the diagnosis at the PPCD.

,Discussion

The primary goal of this study was to develop an interpretative framework of black men’s experiences at the PPCD. The Figure provides a pictorial summary of the framework. Study results indicated that black men come to the PPCD with different emotions and different experiences. Although the majority of the men were NBBM, there is a significantly increasing number of foreign-born black men receiving a diagnosis of prostate cancer in the United States. Given that black men carry a disproportionate burden of the disease, with a significantly higher incidence compared with any other racial group, it is important that tailored services are provided to black men at the PPCD.

We also found that black men came to the PPCD diverse in terms of their ethnicity, health literacy, spirituality, trust in health care system/physician, prior experience with cancer, perceived susceptibility to cancer, delayed time for diagnosis, and fear of diagnosis. Of importance for physicians is that the black race is not homogeneous. There is a significant number of foreign-born blacks at the PPCD, and they often have different cultural beliefs and values compared with NBBM. In addition, some of the foreign-born black men may not have English proficiency and may need a medical interpreter during the PPCD consultation. In addition, a patient’s pre-existing lack of trust in the health care system may have a negative impact on the PPCD consultation. It is thus important that the physician takes the time to instill trust and make the men comfortable during the PPCD consultation.

For some of the men who had fear of a prostate cancer diagnosis and/or prior experience with cancer, cancer fatalism was experienced at the PPCD. Cancer fatalism, defined as an individual’s belief that death is bound to happen when diagnosed with cancer, has been documented as a major barrier to cancer detection and control.15 For example, fatalistic perspectives have been reported to affect cervical cancer,16 breast cancer,17,18 colorectal cancer,19 and prostate cancer20,21 among blacks. It is thus important to effectively address fatalistic beliefs when a man is diagnosed with prostate cancer.