Point of prostate cancer diagnosis experiences and needs of black men: the Florida CaPCaS study

Background Black men are disproportionately affected by prostate cancer and little is known about their experiences at the point of prostate cancer diagnosis (PPCD). Men who self-identify as black are commonly treated in a singular cohort even though they may be of diverse ethnic origin. This is especially important given the increasing number of foreign-born blacks in the United States.

Objective To examine the experiences and needs of ethnically diverse black men at the PPCD to develop an interpretative framework.

Method The research population was black men who had been diagnosed with prostate cancer during 2006-2010. We used a qualitative research design based on grounded theory principles. Using a semistructured interview guide, a trained interviewer collected data on the participants’ PPCD experiences. The data analyses included verifying the narrative data, coding data, and developing an interpretative framework.

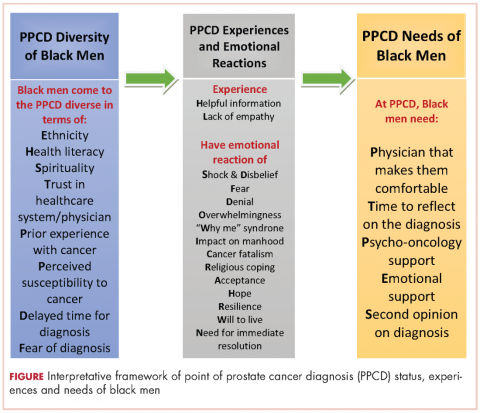

Results From an initial sample of 212 black men, data were collected from 31 participants. The interpretative framework that emerged from the study describes the status of black men at the PPCD, experiences of black men at the PPCD, and emotional reactions of black men at the PPCD. Of note is the need among men at the PPCD for psycho-oncology support, emotional support, and time to reflect on the diagnosis.

Limitations Men with different experiences may have chosen not to respond to recruitment efforts or refused participation in the study.

Conclusion The framework provides information that physicians can use to help their patients cope at the PPCD.

Funding Department of Defense PCRP Award W81XWH1310473.

Accepted for publication December 5, 2016. Correspondence Folakemi Odedina, PhD; fodedina@cop.ufl.edu. Disclosures The authors report no disclosures or conflicts of interest.

JCSO 2017;15(1):10-19. ©2017 Frontline Medical Communications.

doi: https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0323.

Two levels of coding were used. The first, open coding, refers to an approach to data with no preconceived ideas about what will be found; and the second, focused or axial coding, refers to reviewing data for the purpose of more richly coding on a particular theme.11 We used dimensional analysis to ensure that each emerging concept was carefully defined. The study team went back and forth between the data and the emerging analytic framework, using constant comparison of new data with already coded data and new categories with previously analyzed text.12

To ensure trustworthiness and credibility,13 the study team maintained an audit trail that documented how and when analytic decisions were made. In addition, peer debriefing was conducted to ensure credibility, including the presentation of findings to the study community advisory board members as part of the community engaged research approach.

Results

Description of participants

The FCDS provided a database of 1,813 participants identified as black men diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2010. Because the FCDS does not extract data on patients with a death certificate, we found out during the pre-screening phase that a few of the men were deceased. In addition, there were a significant number of incorrect addresses. We obtained a total of 212 completed responses by phone during the prescreening phase. The majority of the participants were aged 60-69 years (48.2%), had a high school diploma only (26.1%), and were currently married (65.3%). Relative to ethnicity, 67% of participants classified themselves NBBM, 24% as CBBM, 3.5% as black men born in Africa, and 5.5% as Other/Don’t know/Refused. For the CBBM, the most common countries of birth were Jamaica, Haiti, and Guyana, respectively.

,In all, 40 participants (20 NBBM and 20 CBBM) were selected from the 212 participants to participate in the study. Selection was conducted systematically to ensure representation in terms of age, marital status, education, and geographical location. Data saturation was achieved with 17 NBBM and 14 CBBM, after which we ended data collection (Table 2). Data saturation is the standard for deciding that we are not finding anything different from the interviews first coded and last coded. Although we were specifically looking for differences between the two groups (NBBM and CBBM), no between-group differences emerged. Each man’s experience was unique to him with some common themes emerging described hereinafter (Figure).

Moderating factors and experiences at PPCD

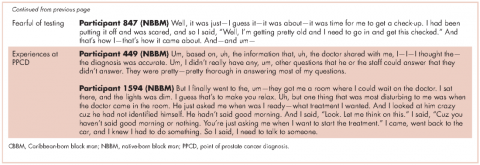

Some of the moderating factors that the study participants identified as affecting their reactions to the PPCD included health literacy, insurance status, spirituality, mistrust, prior experience with cancer, perceived susceptibility to cancer, and delay in diagnosis (Table 3). Health literacy, defined as personal, cognitive, and social skills that determine the ability of individuals to gain access to, understand, and use information to promote and maintain good health, was one of the moderating factors found in this study.13 Some of the black men came to the PPCD with a low level of health literacy, which had an impact on their understanding of the treatment options. For example, in the interview, participant 798 (NBBM) was confused about what tests had been done and was not able to accurately describe the treatments offered to him. Participant 1263 (CBBM) struggled to express the purpose and procedures associated with diagnostic biopsy. However, there were participants with a high level of health literacy (eg, participant 449 [NBBM]), who decided to research the disease.

Another factor to consider is the insurance status of participants at the PPCD. The majority of the participants had good insurance coverage, but some were affected by poor insurance coverage. Participant 1881(NBBM) made his treatment decision primarily on the basis of the pending lapse of his insurance coverage rather than the best clinical option for him. Participant 1979 (CBBM) described both his confusion on the screening tests and the impact of not having insurance coverage. Upon obtaining insurance coverage, he sought treatment for his prostate cancer with an urgency that he did not experience when he was first diagnosed when uninsured.

The spirituality of black men was another moderating factor at the PPCD. Participant 827 (NBBM) noted that he was unaffected when he received his diagnosis because he was a true believer. Some of the black men also came to the PPCD with lack of trust in the physician and/or the health care system and perceived a sense of contempt from the physician. Participant 1594 (NBBM) described mistrust based on the history of medical exploitation of black men as well as a perception of current discriminatory practices.

Another important PPCD status to note for black men is prior experience with cancer, including prior personal cancer history and/or prior cancer history of a family member. Participant 2024 (CBBM) described the meaning of cancer to him, while participant 798 (NBBM) echoed the despair of the cancer diagnosis based on experience with other cancers in the family. Sometimes there were multiple cancers in the family or even among the significant others of the participant, as was the case with Participant 1936 (CBBM).

Of greatest concern were men who delayed their diagnosis or treatment, perhaps resulting in their cancer being at a more advanced stage when they eventually did return for care. Finally, some of the men came to the PPCD appointment with a low expectation of receiving a diagnosis of prostate cancer, whereas others came to the PPCD fearful of the results of their testing.

In describing their experiences, participants expressed both positive and negative experiences: on the positive side, they found the information provided by the physician to be helpful; but on the negative side, the sterile or medically focused encounter was perceived as a lack empathy on the part of the physician.