HIV: 3 cases that hid in plain sight

Having a high index of suspicion is key to recognizing the signs of HIV infection in patients without classic risk factors. How quickly would you have spotted these 3 cases?

He returned to the office in July 2012 with similar symptoms and a 12-pound weight loss since his last visit. He also complained of short-term memory problems. Lab testing was done and included a chemistry panel, thyroid-stimulating hormone test, and CBC, all of which were normal except for a hemoglobin of 11.1 g/dL, a white blood cell count of 2.4/mcL, and a platelet count of 119,000/mcL. The patient was advised to get a follow-up CBC in one month, but this was not done.

Mr. L returned in November 2012, again complaining of intermittent lightheadedness and fatigue, and said he had been experiencing “mouth sores.” He was given a diagnosis of “probable oral herpes infection” and treated with oral acyclovir. No lab studies were performed.

Mr. L was brought to the ED in February 2013 with fever and mental status changes that had developed over 2 to 3 days. According to a family member, he had also complained of headache for the previous 2 weeks.

A CT scan of his head was normal and he underwent a lumbar puncture. Cerebrospinal fluid revealed a white blood cell count of 270/mcL, glucose of 62 mg/dL, and protein of 15 mg/dL. A gram stain was negative, but an India ink stain was positive for encapsulated yeast forms consistent with Cryptococcus. Mr. L was diagnosed with cryptococcal meningitis and treated with intravenous amphotericin B and oral flucytosine. An HIV serology was positive. His CD4+ T-cell count was 8 cells/mm3 (3%) and his HIV RNA level was >500,000 copies /mL.

He was discharged from the hospital after 2 weeks and transitioned to oral fluconazole 400 mg/d for the meningitis. One week after discharge, he was started on an ART regimen of darunavir 800 mg, ritonavir 100 mg, and fixed-dose tenofovir/emtricitabine (200 mg/300 mg).

After 6 months of ART, he showed significant clinical improvement, his HIV-RNA level was <20 copies/mL and his CD4+ T-cell count was 136 cells/mm3 (12%). His female partner of 11 years tested negative for HIV.

The correct diagnosis: Cryptococcal meningitis; thrombocytopenia secondary to HIV infection.

These 3 cases illustrate what clinicians who treat patients with HIV/AIDS have observed for many years: Physicians often fail to diagnose patients with HIV infection in a timely fashion. HIV can be missed when patients present with clinical signs of immune suppression, such as herpes zoster, as well as when they present with AIDS-defining illnesses such as lymphoma or recurrent pneumonia. Late diagnosis of HIV—typically defined as diagnosis when a patient’s CD4+ T-cell count is <200 cells/mm3—increases morbidity and mortality, as well as health care costs.3

Historically, late HIV testing has been very common in the United States. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report noted that from 1996 to 2005, 38% of patients diagnosed in 34 states had an AIDS diagnosis within one year of testing positive for HIV.4 Chin et al5 performed a retrospective cohort study of patients seen in an HIV clinic in North Carolina between November 2008 and November 2011. The median CD4+ T-cell count at time of diagnosis was 313 cells/mm3 and one-third of patients had a count of <50 cells/mm3. Current HIV treatment guidelines recommend ART for all patients diagnosed with HIV infection regardless of CD4+ T-cell count.

The mean number of health care visits in the year before diagnosis was 2.75 (range 0-20). These visits occurred in both primary care settings and the ED. Approximately one-third of patients had complained of HIV-associated signs and symptoms, including recurrent respiratory tract infections, unexplained persistent fevers, and generalized lymphadenopathy prior to diagnosis.

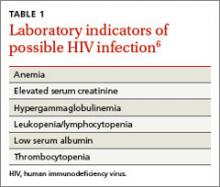

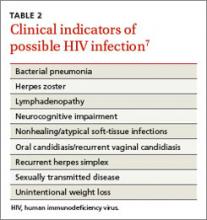

FPs must remain cognizant of the many diverse clinical presentations of patients with HIV/AIDS, including fatigue, weight loss, unexplained rashes, and hematologic disorders (TABLE 16 and TABLE 27). In the 3 cases described here, the specific conditions the treatment teams failed to identify as indicators of HIV infection were thrombocytopenia, pneumocystis pneumonia, herpes zoster, and cryptococcal meningitis.

Thrombocytopenia has many causes, including infection, medications, lymphoproliferative disorders, liver disease, and connective tissue diseases. However, low platelet counts are often seen in individuals with HIV infection.

Before the introduction of ART, the incidence of thrombocytopenia in HIV patients was 40%.8 Since then, this condition is less common, but HIV should be ruled out when evaluating a patient for thrombocytopenia or making a diagnosis of “idiopathic thrombocytopenia” (as was Ms. K’s initial diagnosis).