When to suspect interstitial cystitis

The symptom profile and comorbidities associated with this painful condition can make it difficult to diagnose—unless you know what to look for.

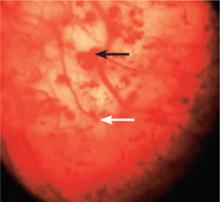

Cystoscopy after hydrodistension, preferably with isotonic saline or isotonic glycine to avoid hypotonic damage to the urothelium, is performed under anesthesia (FIGURE 1). This is the most common procedure performed on patients with IC/BPS29 because it allows visualization of the urothelial glomerulations, or petechiae, and submucosal hemorrhages, found in most patients with this condition. The test would also reveal the presence of the mucosal lesions (Hunner’s ulcers) found in those with “classic” IC/BPS, which represents 5% to 15% of all cases.4

FIGURE 1

IC/BPS: A cystoscopic image

Visualization of the bladder during cystoscopy after hydrodistension reveals submucosal hemorrhages (black arrow) and glomerulations (white arrow), found in most patients with IC/BPS.

Glomerulations can occur in other bladder conditions, however, and may even be found in normal bladders.30 Thus, glomerulations are not diagnostic of IC/BPS in and of themselves, but this finding is often used to confirm the diagnosis.

CASE After Jan’s initial urinalysis, culture, and sensitivity tests, you follow up with a number of other laboratory tests, including CBC with differential, ESR, CRP, and hormonal and immune indexes. All are within the normal range. You also perform a gynecologic examination and use the O’Leary-Sant Symptom and Problem Index to diagnose IC/BPS, and refer the patient to a urologist for further evaluation. The urologist performs cystoscopy with bladder hydrodistension, which reveals multiple submucosal hemorrhages and glomerulations.

Treatment of IC/BPS is multimodal

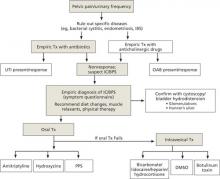

In January 2011, the American Urological Association (AUA) approved diagnostic and treatment recommendations for IC/BPS (available at https://www.auanet.org/content/guidelines-and-quality-care/clinical-guidelines.cfm?sub=ic-bps). The AUA recommends starting with the most conservative treatments, such as stress management, patient education, and self-care. Interventions may include dietary modification (eliminating bladder irritants such as caffeine and alcohol), self-guided imagery, meditation, yoga, deep breathing, self-hypnosis, and manual physical therapy to the pelvic floor myofascial trigger points, with oral or intravesical medications and other procedures added, as needed (FIGURE 2). Pain management, the AUA notes, should be considered throughout the course of therapy.31

FIGURE 2

Treatment algorithm for interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS)

DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; PPS, pentosan polysulfate; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Sources: American Urological Association31; International Incontinence Society (https://www.icsoffice.org/Documents/Documents.aspx?DocumentID=494).

The other professional society with treatment recommendations for IC/BPS is the International Continence Society (https://www.icsoffice.org/Documents/Documents.aspx?DocumentID=494). Because there is no known cure for IC/BPS, the Society focuses on alleviating symptoms and improving the patient’s quality of life. Treatment is highly individual, the Society states, and may consist of diet modification, oral drugs, bladder instillations or injections, and neuromodulation or surgical interventions, as a last resort. Multiple approaches may be used, often together. 29

Both mild discomfort/pain and urinary frequency in newly diagnosed patients may be treated with a number of oral drugs used off label (TABLE 2), as well as with muscle relaxants, such as diazepam. Pentosan polysulfate—the only oral drug with US Food and Drug Administration approval for treatment of IC/BPS—was initially shown to be “modestly beneficial.”32 However, in 2 recent randomized studies, including one multicenter trial funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, it was found to be little (or no) better than placebo.33,34 Thus, we recommend that the drug be tried for no more than 4 to 6 months. If there is no benefit or adverse effects such as GI problems or hair loss develop, the drug should be discontinued.

TABLE 2

Frequently used medications for mild to moderate symptoms

| Agent | Usual dose |

|---|---|

| Amitriptyline | 50-75 mg at bedtime* |

| Diazepam | 2-5 mg up to 4 times per day prn |

| Hydroxyzine | 50-75 mg at bedtime* |

| Pentosan polysulfate | 100 mg tid |

| Pain control | |

| Doxepin cream† | Apply 2-3 times per day |

| Gabapentin | 200 mg tid (starting dose) |

| Tramadol | 100 mg bid |

| *Titrated up over 3-4 weeks. †For vulvodynia. | |

The tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline is often used to relieve symptoms—both urinary frequency and pain/discomfort—that are mild to moderate. In one small clinical trial, amitriptyline (self-titrated up to 100 mg/d for 4 months) produced a 64% response rate. But nearly a third of the patients in the intervention group (and many more on placebo) dropped out due to nonresponse.35 A recent multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of amitriptyline showed that only patients who took >50 mg daily had a significantly higher response rate (P=.01) compared with the placebo group.36

Amitriptyline may also be combined with hydroxyzine, especially in patients with allergies, but the combination could result in considerable sedation. The antidepressant doxepin, which is both a histamine-1 (H1) and histamine-2 (H2) receptor antagonist (RA), is an alternative that has been shown to reduce chronic neuropathic pain.37 A doxepin cream may also be used locally for vulvodynia.

Although no comparative studies have been conducted, nontricyclic antidepressants do not appear to have the same benefit for IC symptoms. In an open-label study of 48 women with IC/BPS, the antidepressant duloxetine (titrated to 40 mg bid for 5 weeks) showed no significant improvement of symptoms.38