Insomnia diagnosis and treatment across the lifespan

Insomnia impairs quality of life and is associated with an increased risk for physical and mental health problems and substance misuse. Here’s how you can help.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Use a standard validated screening tool for the diagnosis of insomnia in all age groups. A

› Employ nonpharmacologic interventions as first-line treatment for insomnia in all populations. A

› Utilize sleep hygiene or cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in adolescents and all adults. A

› Initiate independent cognitive or behavioral therapies with younger children. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Multiple randomized and nonrandomized studies have found that infants also respond to behavioral interventions, such as establishing regular daytime and sleep routines, reducing environmental noises or distractions, and allowing for self-soothing at bedtime.55 A controlled trial (N = 279) of newborns and their mothers evaluated sleep interventions that included guidance on bedtime sleep routines, starting the routine 30 to 45 minutes before bedtime, choosing age-appropriate calming bedtime activities, not using feeding as the last step before bedtime, and offering the child choices with their routine.56 The intervention group demonstrated longer sleep duration (624.6 ± 67.6 minutes vs 602.9 ± 76.1 minutes; P = .01) at 40 weeks postintervention compared with the control group.56

The clinically significant outcomes of this study are related to the guidance offered to parents to help infants achieve longer sleep. More intervention-group infants were allowed to self-soothe to sleep without being held or fed, had earlier bedtimes, and fell asleep ≤ 15 minutes after being put into bed than their counterparts in the control group.56

Exercise. As a sole intervention, exercise for insomnia is readily available and low cost, but it is not universally effective. One study of patients older than 60 years (N = 43) showed that a 16-week moderate exercise regimen slightly improved total sleep time by an average of 42 minutes (P = .05), sleep-onset latency improved an average of 11.5 minutes (P = .007), and global sleep quality improved by 3.4 points as measured by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI; P ≤ .01).57 No significant improvements occurred in sleep efficiency. Exercise is one of several nonpharmacologic alternatives for treating insomnia in pregnancy.58

A lack of uniformity in patient populations, intervention protocols, and outcome measures confounded results of 2 systematic reviews that included comparisons of yoga or tai chi as standalone alternatives to CBT-I for insomnia treatment.58,59 Other interventions, such as mindfulness or relaxation training, have been studied as insomnia interventions, but no conclusive evidence about their efficacy exists.45,59

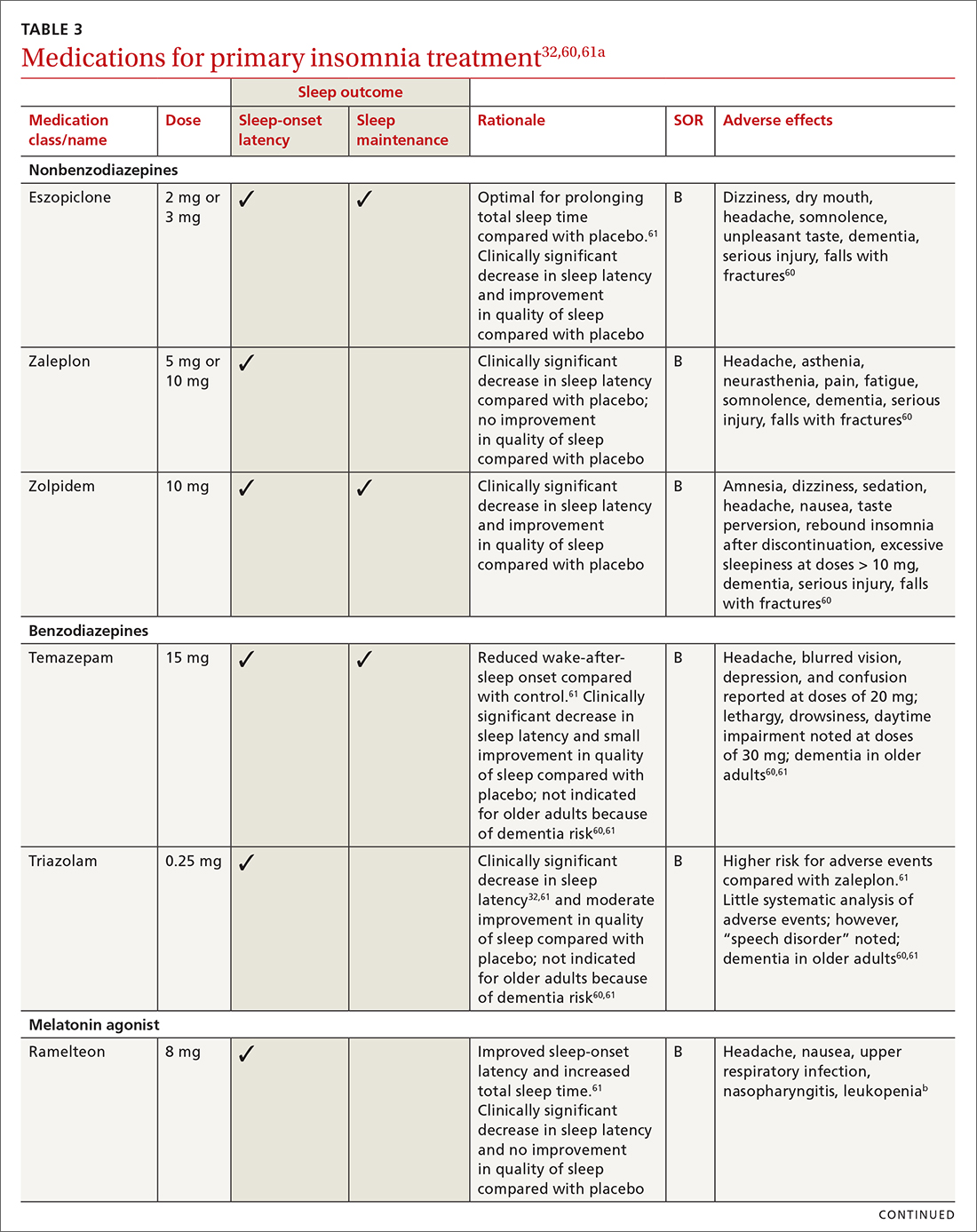

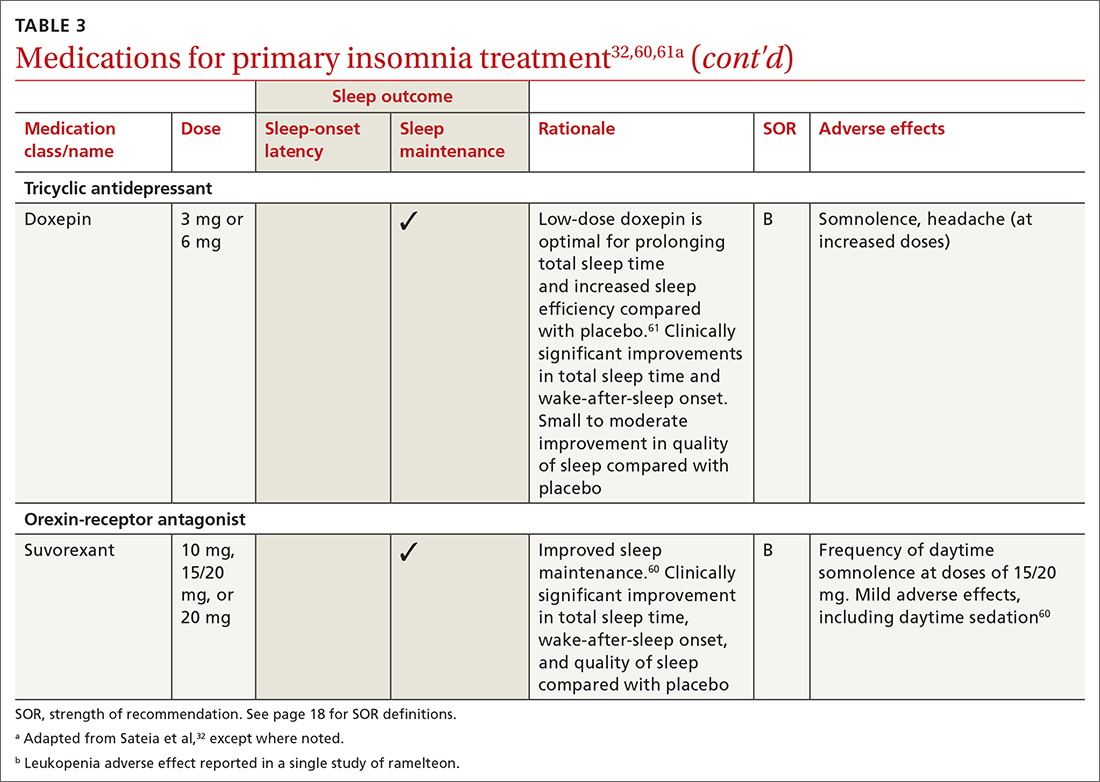

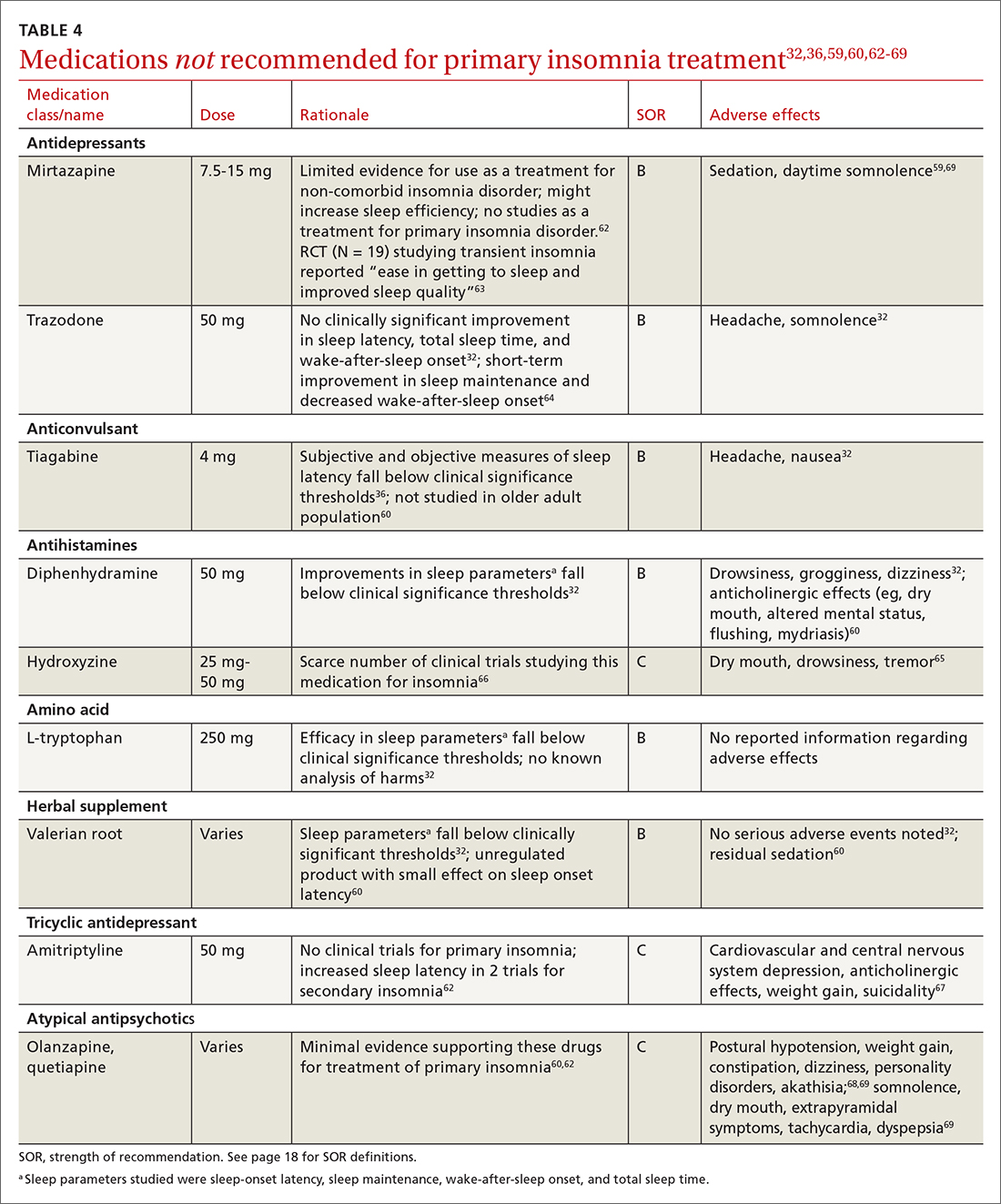

Pharmacologic interventions

Pharmacologic treatment should not be the sole intervention for the treatment of insomnia but should be used in combination with nonpharmacologic interventions.32 Of note, only low-quality evidence exists for any pharmacologic interventions for insomnia.32 The decision to prescribe medications should rely on the predominant sleep complaint, with sleep maintenance and sleep-onset latency as the guiding factors.32 Medications used for insomnia treatment (TABLE 332,60,61) are classified according to these and other sleep outcomes described in TABLE 1.25-29 Prescribe them at the lowest dose and for the shortest amount of time possible.32,62 Avoid medications listed in TABLE 432,36,59,60,62-69 because data showing clinically significant improvements in insomnia are lacking, and analysis for potential harms is inadequate.32

Continue to: Melatonin is not recommended