Standardizing your approach to dizziness and vertigo

First, determine whether the sensation the patient is experiencing is dizziness or true vertigo. Then eliminate ominous causes from the array of benign ones.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Employ the Dix-Hallpike maneuver to diagnose patients presenting with dizziness with features suggestive of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). A

› Use the head impulse, nystagmus, test of skew (HINTS) examination to differentiate between central and peripheral vestibular causes of dizziness and rule out stroke. B

› Prescribe betahistine only for patients with Meniere’s disease and not for patients with other causes of dizziness and/or vertigo. B

› Rely on antiemetics, antihistamines, and benzodiazepines to manage acute and brief episodes of vertigo, but not to treat BPPV because they blunt central compensation. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

From The Journal of Family Practice | 2018;67(8):490-492,495-498.

Peripheral vestibular causes. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) represents the most common peripheral diagnosis. It is caused by dislodged otoliths in the posterior semicircular canal. While the majority of BPPV cases are idiopathic in nature, up to 15% may result from previous head injury.14 Other peripheral vestibular causes include vestibular neuronitis, viral labyrinthitis, Meniere’s disease, vestibular schwannoma, perilymphatic fistula, superior semicircular canal dehiscence (SSCD), and head trauma (basilar skull fracture).13

Start with a history: Is it dizziness or true vertigo?

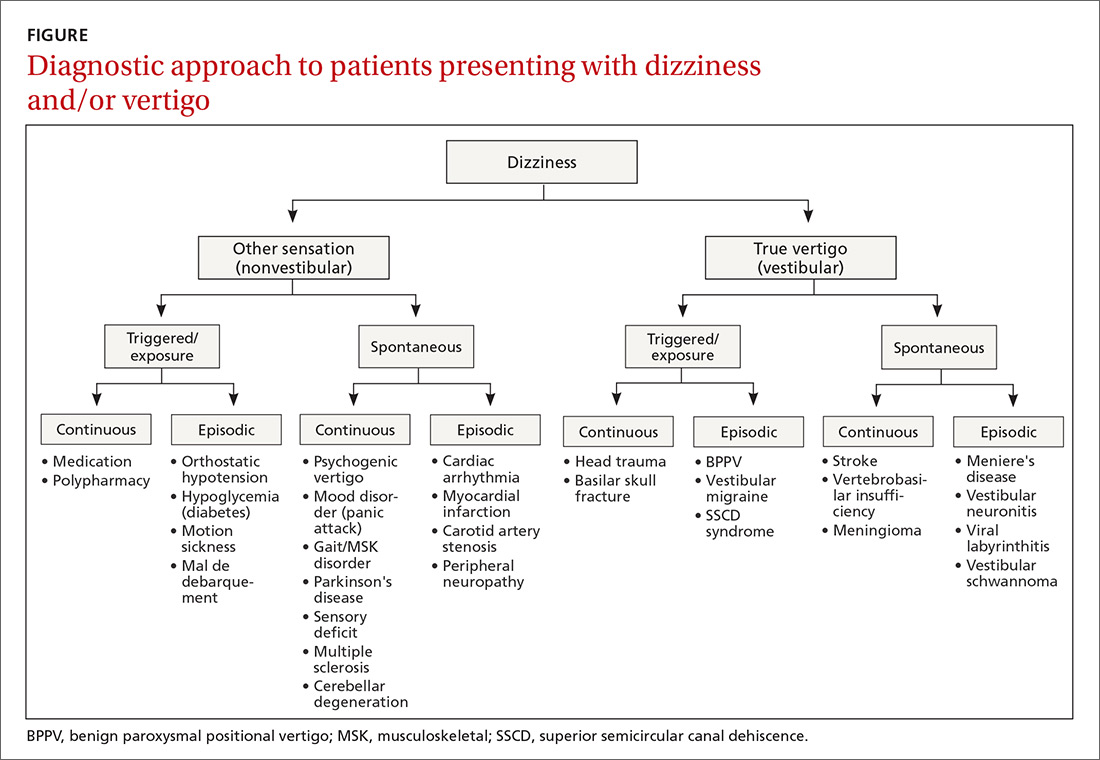

The clinical history typically guides the differential diagnosis (FIGURE). Identifying true vertigo from among other sensations helps to limit the differential because true vertigo is caused by vestibular etiologies only. True vertigo is often reported by patients as “seeing the room spin;” this stems from the perception of motion.1 A notable exception is that patients with orthostatic hypotension will often describe spinning sensations lasting seconds to minutes when they rise from a seated or supine position.

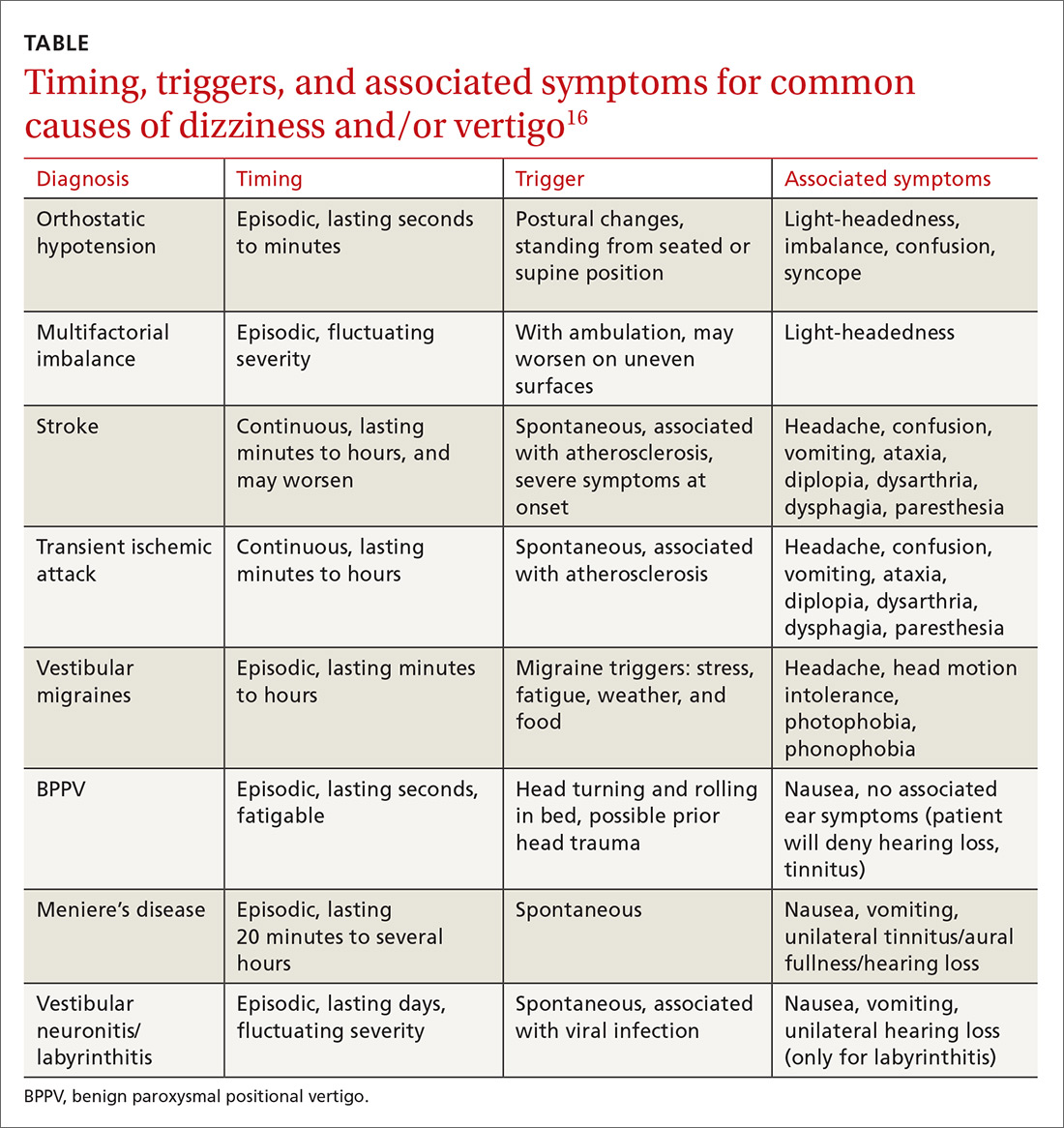

Never depend solely, however, on patient-reported sensations, as not all patients with true vertigo report spinning, and some patients with nonvestibular causes interpret their dizziness as a spinning sensation.15 Therefore, it is important to tease out specifics about the timing, triggers, and associated symptoms in order to further delineate possible causes (TABLE).16

Make a list of current medications. Gather a comprehensive list of current medications, especially from elderly patients, because polypharmacy is a major contributor to dizziness in this population.12 Keep in mind that elderly patients presenting with dizziness/vertigo may have multifactorial balance difficulties, which can be revealed by a detailed history.

Physical exam: May be broad or focused

Given the broad range of causes for dizziness, cardiovascular, head/neck, and neurologic examinations may be performed as part of the work-up, as the clinical history warrants. More typically, time is spent ruling out the following common causes.

Continue to: Orthostatic hypotension