Drug-induced weight gain: Rethinking our choices

Weight gain secondary to medications is a potentially modifiable risk. Here’s how to optimize drug choices for patients with several common conditions.

When a different drug in the same class will do

There are exceptions, however. When beta-blockers are required—for patients with coronary artery disease, heart failure, or an arrhythmia, for example—a selective agent with a vasodilating component, such as carvedilol or nebivolol, is recommended.2 These drugs appear to have less potential for weight gain and to have minimal effect on lipid and glucose metabolism.26,27

In a study of 1106 patients with hypertension, those taking metoprolol had a statistically significant mean weight gain of 1.19 kg (P<.001) compared with patients taking carvedilol (mean weight gain, 0.17 kg; P=.36).24 While 4.5% of those in the metoprolol group gained ≥7% of their body weight, that was true of only 1.1% of those taking carvedilol. Thus, weight gain can sometimes be minimized by choosing a different medication within the same drug class.

ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and calcium channel blockers

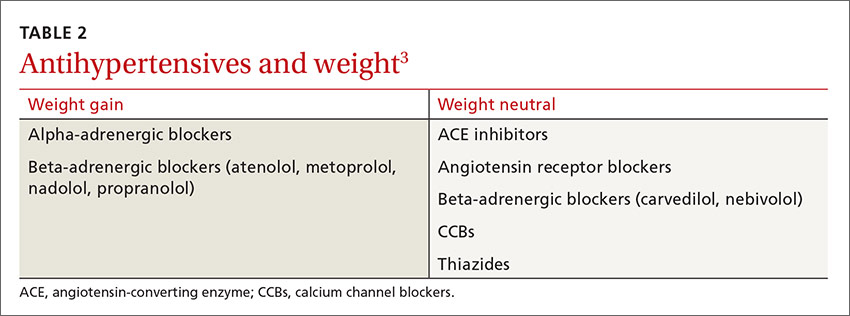

Antihypertensive medications that are not associated with weight gain or insulin resistance include angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), and calcium channel blockers (CCBs) (TABLE 2).3 Angiotensin contributes to obesity-related hypertension, as it is overexpressed in obesity, making ACE inhibitors and ARBs desirable options for the treatment of patients who are obese. And, because many patients who are obese also suffer from type 2 diabetes or prediabetes, they’re likely to benefit from the renal protection provided by ACE inhibitors and ARBs, as well.

CASE 2 › Switching antihypertensives

Switching Ms. K from metoprolol, a beta-blocker, to an ACE inhibitor, ARB, or CCB may help prevent further weight gain, and possibly even lead to weight loss. Any drug in any of these 3 classes of medications would be a reasonable choice. However, if the patient had a condition that warranted use of a beta-blocker, a selective agent with a vasodilating component such as carvedilol or nebivolol might be helpful.

SIDEBAR

Weight management strategies for several other conditionsIn addition to medications for common conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and depression, there are numerous other drugs that can cause unwanted weight gain. These include some antiseizure agents, antipsychotics, contraceptives, hormones, and migraine therapies, as well as corticosteroids. In view of both the nation’s obesity epidemic and the many drugs that are known to adversely affect weight maintenance, it is crucial to do a careful risk-benefit analysis and a search for alternatives whenever you prescribe a new medication for a patient who is overweight or obese or has metabolic risk factors.2-5

When weight-neutral substitutes exist, such medications should be considered, if appropriate, to prevent or lessen pharmacologic weight gain. For example, topiramate and zonisamide are preferable to other antiepileptics, such as valproic acid and gabapentin when it comes to weight management.2-4 It is essential to keep in mind, however, that medications in the same class are not always interchangeable.

For patients with inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are preferable to corticosteroids whenever possible.2-4 For the many patients for whom steroids or other drugs known to cause weight gain are necessary, however, dietary and lifestyle counseling—advising patients to eat a healthful diet and maintain adequate activity levels, among other interventions—may help to mitigate the effects.

And when there are no alternative medications available, use the lowest possible dose for the shortest duration necessary.

Choosing an antidepressant when weight is an issue

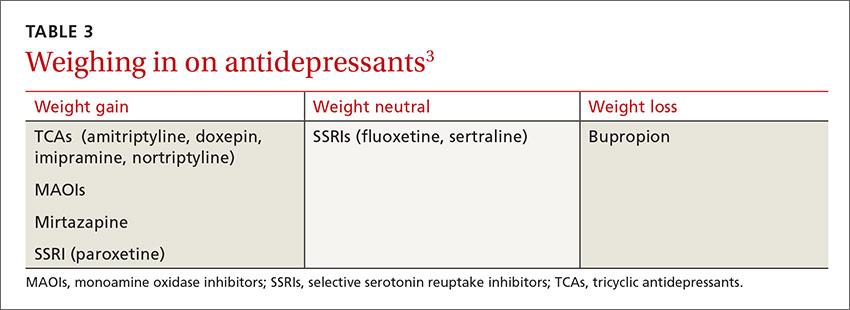

For patients with psychiatric conditions, weight gain is often multifactorial. One key issue: Weight gain is a common adverse effect of many antidepressants (TABLE 3).3 Within classes of antidepressants, there is a range of weight gain potential, which can vary depending on the duration of therapy.2

In a meta-analysis of 116 studies, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as fluoxetine and sertraline were associated with weight loss in short-term use (4-12 weeks) and weight neutrality when used for >4 months.1 Patients who had type 2 diabetes as well as depression had an average weight loss from fluoxetine of 5.1 kg (3.3–6.9 kg) at 24- to 26-week follow up.28

Among SSRI and tricyclic (TCA) antidepressants, paroxetine and amitriptyline, respectively, had the greatest risk for weight gain.1,29 No significant weight effect was observed for either citalopram or escitalopram. Keep in mind, however, that the effect of each antidepressant on weight may vary greatly from one patient to another.1 For example, while Mr. D gained 3.6 kg on paroxetine, some patients gain no weight at all.

In the systematic review and meta-analysis of 257 RCTs, weight gain was associated with the use of amitriptyline (1.8 kg) and mirtazapine (1.5 kg), while weight loss was associated with bupropion and fluoxetine (-1.3 kg for each).8