Headaches

Although most headache presentations to the ED are of benign etiology, there are several potentially life-threatening conditions for which the emergency physician should have a high index of suspicion based on symptoms. This special feature reviews migraine, thunderclap headache, and uncommon—but potentially serious and life-threatening—causes of headache.

Conclusion

Headache is a common presenting complaint in the ED. Once it has been determined that a patient suffers from a primary headache disorder, it is not always relevant or necessary to determine from which headache subtype a patient suffers prior to treatment because most types respond to acute treatment. Multiple regimens have been shown effective for the treatment of acute migraine. Emergency physicians can choose a therapy based on medication availability, provider comfort with the medications, and patient comorbidities.

Opioids should almost never be used as initial treatment in patients presenting with migraine to the ED for the first time because they are less effective than other medications and may worsen the underlying migraine disorder. Once the acute pain is resolved, the EP should administer corticosteroids and discharge the patient with naproxen or a triptan (or a combination therapy) in the event of rebound headache.

Dr Nerenberg is an assistant professor, department of emergency medicine, Albert Einstein College of Medicine Montefiore Medical Center Bronx, New York. Dr Friedman is an associate professor, department of emergency medicine, Albert Einstein College of Medicine Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, New York.

Thunderclap Headache

Jonathan A. Edlow, MD

All patients presenting with thunderclap headache, including the neurologically intact, require a thorough evaluation to distinguish between benign and serious causes.

Among the 4% of ED patients presenting with headache, only a small percentage has serious “cannot miss” causes defined as treatable problems that are life, limb, brain, or vision threatening1,2 (Table 1). Some of these patients have abrupt, severe, and unique headaches referred to as a thunderclap headache. Thunderclap headaches begin suddenly, peak within 60 seconds and can last minutes to days.3 Any patient with a new-onset headache associated with new neurological deficits should be worked up sufficiently to explain the deficit. However, many patients—even those with headaches caused by serious secondary causes—have normal neurological examinations. This article reviews the diagnosis of neurologically intact patients with thunderclap headache.

Most of the “cannot miss” conditions can present with a thunderclap headache, though some are far more common than others. In an unselected ED population of 100 patients with thunderclap headache, approximately 88% to 89% will have nonserious causes; 10% will have subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH); and the remaining 1% to 2% of patients will have one of several rare but important conditions.

The 88% to 89% comprises primary headache syndromes—first migraine or tension-type headache or “benign thunderclap headache,” which means that the workup for serious secondary causes was unrevealing. Because history and physical examination alone cannot distinguish between patients with benign causes of thunderclap headache from those with serious causes such as SAH, all thunderclap headache patients—even those who are entirely intact neurologically—need a thorough evaluation for SAH.1-4 This is consistent with the recent clinical decision rule to identify headache patients with SAH, in which thunderclap presentation mandates a workup for SAH.5

Despite the simplicity of a workup for SAH, studies reveal that emergency physicians (EPs) miss approximately 5% of cases.6,7 For a life-threatening and highly treatable condition, missing one in 20 is problematic.

Evaluation of SAH

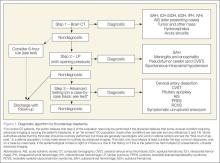

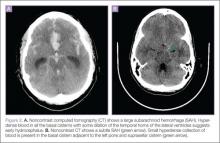

The time-honored evaluation for possible SAH is noncontrast brain computerized tomography (CT) followed by a lumbar puncture (LP) if the CT is normal or nondiagnostic (Figure 1). The accuracy of this paradigm approaches 100%. Computed tomography scans in patients with SAH show blood, which appears white in the acute phase, in the subarachnoid spaces (Figure 2). Sensitivity of CT decreases with time from headache onset and with size of the bleed. The brisk flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which is replaced several times per day, dilutes the blood. Modern CT scanners are only about 90% sensitive in neurologically intact patients, although it is very important to note that this study did not report the time from onset of headache.8

There are two typical locations for SAH to occur: the basal cisterns (usually aneurysmal) and over the high convexities (rarely, if ever, caused by aneurysms). The two common causes of convexal SAH are amyloid angiopathy in older patients and reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS) in younger patients.9 In some cases, CT will suggest another (non-SAH) cause of thunderclap headache. For example, although CT is not 100% sensitive for a small tumor or absces

s, it will nearly always show some abnormality (eg, edema, hydrocephalus, displacement of tissue) in a mass large enough to cause a severe headache. Computed tomography may also show nonspecific changes that warrant further imaging—eg, some cases of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) and other conditions discussed below.